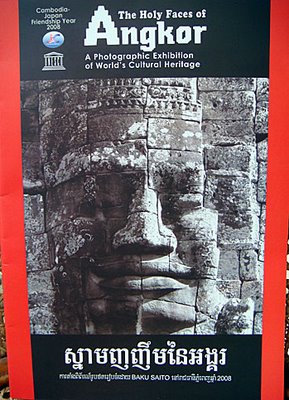

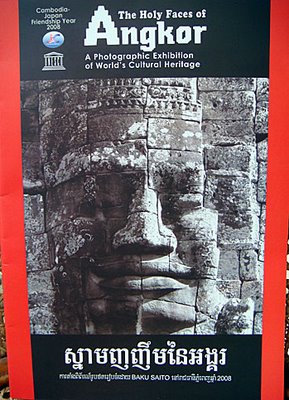

This is the brochure cover for the exhibition

The Holy Faces of Angkor, which is as close as I got to see the exhibit of sixty photographs by Japanese freelance snapper Baku Saito! The exhibition kicked off early on Saturday morning with speeches by Sok An and Veng Sereyvuth, two of the government's top guns as well as Baku himself. Unfortunately I wasn't aware of the morning ceremony at the HQ of CJCC on Russian Boulevard and got there a little after 2pm, to find that the exhibition had already closed for the day and wouldn't reopen until Tuesday. Its on until 31 may, so I will see it in due course, but Saturday's frustration was just the start. It then rained for an hour but before I left I liked the look of the fancy little circular building next to CJCC and was told it was one of renowned Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann's creations. In fact it turns out to be the Institute of Foreign Languages library and is modeled after traditional woven palm-leaf hats and is set in its own small, circular moat. I headed for the Olympic Stadium intending to see a game of football from the Cambodian Premier League, only to be told all games were off this weekend, though I could try the Old Stadium. Now taken over by the Army, the pitch was being watered and looked lush, but there were no games here either. Damn. Even the Cambodia versus Palestine match next Saturday has been cancelled. Down in the dumps, I headed home only to find my internet connection was down too, the first time in the half a dozen months I've been online at home. It was just one of those afternoons I guess.

This circular Vann Molyvann creation sits next to the Cambodian-Japanese Co-Operation HQ on Russian Boulevard and is the library of the Foreign Languages Institute

This circular Vann Molyvann creation sits next to the Cambodian-Japanese Co-Operation HQ on Russian Boulevard and is the library of the Foreign Languages Institute

This is the brochure cover for the exhibition The Holy Faces of Angkor, which is as close as I got to see the exhibit of sixty photographs by Japanese freelance snapper Baku Saito! The exhibition kicked off early on Saturday morning with speeches by Sok An and Veng Sereyvuth, two of the government's top guns as well as Baku himself. Unfortunately I wasn't aware of the morning ceremony at the HQ of CJCC on Russian Boulevard and got there a little after 2pm, to find that the exhibition had already closed for the day and wouldn't reopen until Tuesday. Its on until 31 may, so I will see it in due course, but Saturday's frustration was just the start. It then rained for an hour but before I left I liked the look of the fancy little circular building next to CJCC and was told it was one of renowned Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann's creations. In fact it turns out to be the Institute of Foreign Languages library and is modeled after traditional woven palm-leaf hats and is set in its own small, circular moat. I headed for the Olympic Stadium intending to see a game of football from the Cambodian Premier League, only to be told all games were off this weekend, though I could try the Old Stadium. Now taken over by the Army, the pitch was being watered and looked lush, but there were no games here either. Damn. Even the Cambodia versus Palestine match next Saturday has been cancelled. Down in the dumps, I headed home only to find my internet connection was down too, the first time in the half a dozen months I've been online at home. It was just one of those afternoons I guess.

This is the brochure cover for the exhibition The Holy Faces of Angkor, which is as close as I got to see the exhibit of sixty photographs by Japanese freelance snapper Baku Saito! The exhibition kicked off early on Saturday morning with speeches by Sok An and Veng Sereyvuth, two of the government's top guns as well as Baku himself. Unfortunately I wasn't aware of the morning ceremony at the HQ of CJCC on Russian Boulevard and got there a little after 2pm, to find that the exhibition had already closed for the day and wouldn't reopen until Tuesday. Its on until 31 may, so I will see it in due course, but Saturday's frustration was just the start. It then rained for an hour but before I left I liked the look of the fancy little circular building next to CJCC and was told it was one of renowned Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann's creations. In fact it turns out to be the Institute of Foreign Languages library and is modeled after traditional woven palm-leaf hats and is set in its own small, circular moat. I headed for the Olympic Stadium intending to see a game of football from the Cambodian Premier League, only to be told all games were off this weekend, though I could try the Old Stadium. Now taken over by the Army, the pitch was being watered and looked lush, but there were no games here either. Damn. Even the Cambodia versus Palestine match next Saturday has been cancelled. Down in the dumps, I headed home only to find my internet connection was down too, the first time in the half a dozen months I've been online at home. It was just one of those afternoons I guess.

2 Comments:

Cambodian Modern: The Architectural Legacy of Vann Molyvann

- by Stephen Brookes • Modernism Magazine • Winter 2007-08

It’s a still, clear morning in Phnom Penh, but storm clouds are gathering over one of the city’s most striking buildings. Empty and abandoned in an unkempt field, the light, sleek lines of the National Theater rise unexpectedly into the air, soaring over the bland office blocks and Buddhist temples nearby. With its sharp angles, walls of glass and playful interior spaces, it’s a tour de force of 1960’s modernism – utterly original, and as captivating as a mirage.

Designed in 1964 by the innovative Khmer architect Vann Molyvann, the theater is only one of dozens of important -- yet still little-known -- modernist buildings in Cambodia, all built during a spectacular architectural flowering between 1953 and 1970. Fusing European modernist ideas with Khmer vernacular architecture, Molyvann almost single-handedly changed the face of Phnom Penh, launching what’s come to be known as “New Khmer Architecture.” And while many of his masterpieces are under threat from new development, they still comprise one of the most intriguing collections of modernist architecture in Asia.

Known in the 1930’s as “the Pearl of the Orient,” Phnom Penh today is an open, low-slung city of broad avenues and tree-lined lanes, with an eclectic mix of pale yellow colonial villas, bland apartment blocks, elegant art deco buildings, graceful temples and tiny houses jammed up chockablock against each other.

And over the past decade, it’s been slowly coming to life. Cambodia spent most of the 20th Century enduring one nightmare after another – colonized by France, dragged into the Vietnam war, embroiled in civil strife, subjected to the horrors of the Khmer Rouge (when Phnom Penh was emptied) and invaded by the Vietnamese. And even now, though political stability seems to be restored, the country remains poor, corrupt and largely isolated.

But there was one bright moment in the years right after the country’s 1953 independence from France. Determined to make the capital a symbol of Cambodia’s forward-looking, confident attitude, the ruling Prince Norodom Sihanouk commissioned more than 100 new buildings from a group of architects – led by the young Vann Molyvann, who had recently returned from studying with Le Corbusier at l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Barely thirty, Molyvann was just four years younger than Sihanouk himself, and the two made a formidable team. There were already several modern architectural gems in the city, like the cruciform, deco-inspired Central Market from 1937 and the Phnom Penh Railway Station from 1932. But Molyvann had absorbed Le Corbusier’s ideas and wanted to infuse them with a distinctly Khmer sensibility, using elements from the ancient temples of Angkor and paying particular attention to the problems of flooding and extreme heat that Cambodia endures.

“We could not simply repeat things as they were done in Europe,” says Molyvann, who, at 81, still lives in the airy, light-filled house on Mao Tse Tung Boulevard he designed for himself in the late 1960’s. “We needed to think with new ideas, to build with a Cambodian approach.”

Many of those new ideas are embodied in what may be Molyvann’s most important work, the National Sports Complex. Built in 1963-64, it’s vast without being grandiose -- a 60,000-seat stadium, an 8,000 seat indoor sports hall, Olympic sized swimming pools and tennis courts, all seamlessly integrated in a 96-acre landscape of open courtyards and ornamental pools.

With its bold, muscular contours, the main sports hall makes an appropriately athletic statement. But inside, there’s a surprising openness to it; light and air filter in freely through the vented walls, and pools and streams run along the walkways, cooling the air and helping control the deluges of the monsoon.

And almost everywhere, there are references to the iconic temples of Angkor, which lie at the heart of Cambodia’s identity. The stadium’s pools echo the vast reservoirs -- known as “barays” -- which surround the temples to store water and contain flooding, while the elevated walkways reflect the massive one that leads into Angkor Wat. Even the louvered walls, which keep heat out but allow light in, reference the ancient temples.

That lively interplay between European modernism and Khmer vernacular architecture can be seen in virtually all of Molyvann’s buildings. The Independence Monument (1960), with its distinctive lotus-bud shape, emulates the Arc de Triomph yet is modeled on the central tower of Angkor Wat. The National Theater integrates the traditional “barays” with modern suspended staircases and cantilevered triangular roofs. And the Chaktomuk Conference Hall, though thoroughly contemporary, was modeled on the shape of the fan palm – a plant virtually emblematic of Cambodia’s rural villages.

Some of the most overt references to Angkor can be found at the Institute for Foreign Languages, next to the Royal University of Phnom Penh on Pochentong Boulevard. In homage to the kilometer-long entry passage at Angkor, it’s reached via a long elevated concrete walkway that leads to the main building. The walkway even includes modernist versions of “nagas” – the stone serpents that guard the Angkor temples.

And here, too, modern materials have been adapted to traditional uses. While the buildings are largely brick and concrete, they are designed to minimize direct sunlight, maximize airflow and control the risk of flooding. But there’s a whimsical quality about them, as well; the Institute’s library is modeled after traditional woven palm-leaf hats (and is set in its own small, circular moat), and the lecture halls are cantilevered imaginatively out over angled “legs” that give them a coiled, animal-like energy.

The Institute for Foreign Languages is still in active use, as are many of Molyvann’s other enduring designs, including the Ministry of Finance, the Council of Ministers, and the “100 Houses” residential housing project. But others are decaying, and many are threatened by the helter-skelter development now underway almost everywhere in the city. Real estate speculation and a lack of oversight, says Molyvann, have resulted in reckless building – with little respect for the environment or Cambodia’s architectural heritage.

A planned renovation of the National Sports Complex, for example, has turned into a disaster. A Taiwanese company was given the contract to restore the main buildings in 2000, in exchange for the right to build on some of the surrounding grounds. But the developers filled in Molyvann’s carefully planned ponds (leading to flooding in the area), threw up a cheap, ugly retail building next to the stadium, and haven’t even begun the renovation.

The National Theater (also known as the Tonle Bassac Theater) faces an even more urgent threat. It’s been steadily deteriorating since a fire gutted much of it in 1994, destroying the distinctive glass pyramid at its top. Cambodia’s current King, Norodom Sihamoni, has said that he wants to see it rebuilt, but no funding has been provided, and the Theater is largely boarded up. A local telecommunications company, meanwhile, is reported to want the site for other uses.

“The land there is too valuable now,” says Molyvann, sitting at a book-filled desk in his home in Phnom Penh, “and it’s expensive to renovate. The Bassac Theater will be destroyed. They want to put in a department store.”

For other buildings, it may already be too late. Molyvann introduced apartment blocks to Cambodia with his two Front du Bassac buildings from the mid-1960’s, designed along Le Corbusier’s idea of the “modular.” Once landmarks, their striking design has largely been obliterated. One was renovated beyond all recognition, turned into a faceless box and renamed, ironically, the “Build Bright University.” The other is in terrible condition and is likely to be torn down, says one architect in Phnom Penh, to make room for a 46-story development.

“We’re starting to introduce property rights, respect for law and so on,” says Molyvann, as the sound of construction drifts up from the busy street below. “But I’m concerned about the future. In ten years, I don’t know what will be left.”

Part of a book review by Andrew Symon for AsiaTimes in Oct 2007 reveals the following...

'One structure that especially stands out is the Institute of Languages, formerly the library for the teacher's training college. It is a small but striking circular building whose form was inspired by the traditional Khmer woven palm leaf hat still worn throughout the countryside - though the structure makes use of ribs of concrete rather than rattan.

Designed by Vann Molyvann, one of the most influential of the Khmer architects, and today still living in Phnom Penh, its circular concrete roof is indented with concrete rays and seems to almost float in a circular glass wall. Inside light is filtered by the careful location of windows so that the interior is not exposed to intense illuminant contrasts.

Architects like Molyvann (as well as the economists, political scientists and lawyers, including those who would lead the Khmer Rouge) who went abroad to study after World War II were the first Cambodians of any significant number to do so. They returned, Ross and Collins note, with both the new ideas of Western modernism - the simplification of form and design following function - with designs and motifs inspired by Cambodian historical and contemporary architectures built in harmony with the country's tropical environment.

For instance, glass was not used on the extensive scale common to Western modernist buildings of the era. Rather - and sensibly so - there was great reliance on open spaces and verandahs allowing natural ventilation. Water was often used as moats around buildings and in courtyard ponds. Spaces under buildings are common as well as roof terraces. Concrete was often combined with brick and stone.'

Post a Comment

<< Home