Rithy Panh's latest

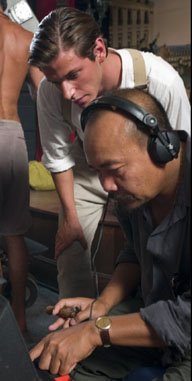

Rithy Panh, Cambodia's best-known international film director, launched his latest work, The Sea Wall (Un barrage contre le Pacifique), at the Toronto Film Festival yesterday. Panh, with critically-acclaimed films such as Rice People, S-21, Burnt Theatre and lots more under his belt has moved into more mainstream cinema with his newest work adapted from a classic French novel and includes the successful French actress Isabelle Huppert amongst a strong cast. It should be out at cinemas before the end of the year after another festival screening in Rome.

Here's a review of the film by Howard Feinstein of ScreenDaily.com.

The poor, emaciated widow and mother of two in colonial Cambodia portrayed by Isabelle Huppert in this potent adaptation of Marguerite Duras’s novel is as far from Catherine Deneuve’s portrait of a glam, well-coiffed landowner in French-occupied Vietnam in Regis Garnier’s Indochine as the two films are from each other. The Sea Wall is directed by Rithy Panh, a Cambodian-born filmmaker who now resides in France, a man who proved he could capture the feel, the tropical textures and sounds of his native country as far back as Rice People (1994). Garnier’s Indochine, in contrast, was overblown, brushed with a varnish that disguised the realities of imperialism in tropical climes. Panh is not afraid to reveal the worms in a gorgeous world of lush palms and attractive rice paddies in what might be construed as paradise, a concept literalised in the film. The lack of gloss may cost this multilayered movie some of its potential audience, but the mix of natural beauty, period politics, and powerful acting, especially on the part of Huppert, should bring in sufficient aficionados of fine arthouse fare.

The Sea Wall is set in the early 1930s, when cruel oppression by French bureaucrats and soldiers and their Cambodian collaborators was fanning the first flames of revolution. Huppert’s mother is a former schoolteacher from France who moved to Cambodia 20 years earlier with her civil-servant husband. She bore him two children, virile 19-year-old Joseph (Ulliel) and beautiful tease Suzanne (Berges-Frisbey), 16, neither of whom has ever been out of the country. The paddies that so determined the fate of the peasants in Rice People perform a similar function here, though in The Sea Wall the lives of both colonists and indigenous peasants are determined by the condition of the fields. In the latter film, a weak sea barrier collapses regularly, allowing salt water to flood and ruin the new crop. Like the rice itself, the mother is slowly dying from the whims of nature and from the incompetence and blatant corruption of the French bureaucrats she is unafraid to confront. She also tries to organize the Cambodians so that they will strengthen the wall and refuse to give up their land.

An extremely wealthy son of a Chinese capitalist, Monsier Jo (Douc), arrives not on a shiny white horse but in a shiny new luxury car. He becomes obsessed with Suzanne, whom he impresses by showering her with expensive gifts. Her mom, worried about losing her land, and even her racist brother are not above pushing her into marriage for money. Yet this handsome man, who at first appears merely a spoiled dandy, turns out to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. In collusion with the French, he uproots the locals from their land, burning their homes and treating like criminals on a chain-gang march. The dying mother correctly predicts that one day the children of her devoted Cambodian servant, nicknamed Colonel (Vathon), will rise up against their European overlords.

For more on the films of Rithy Panh, click here.

Here's a review of the film by Howard Feinstein of ScreenDaily.com.

The poor, emaciated widow and mother of two in colonial Cambodia portrayed by Isabelle Huppert in this potent adaptation of Marguerite Duras’s novel is as far from Catherine Deneuve’s portrait of a glam, well-coiffed landowner in French-occupied Vietnam in Regis Garnier’s Indochine as the two films are from each other. The Sea Wall is directed by Rithy Panh, a Cambodian-born filmmaker who now resides in France, a man who proved he could capture the feel, the tropical textures and sounds of his native country as far back as Rice People (1994). Garnier’s Indochine, in contrast, was overblown, brushed with a varnish that disguised the realities of imperialism in tropical climes. Panh is not afraid to reveal the worms in a gorgeous world of lush palms and attractive rice paddies in what might be construed as paradise, a concept literalised in the film. The lack of gloss may cost this multilayered movie some of its potential audience, but the mix of natural beauty, period politics, and powerful acting, especially on the part of Huppert, should bring in sufficient aficionados of fine arthouse fare.

The Sea Wall is set in the early 1930s, when cruel oppression by French bureaucrats and soldiers and their Cambodian collaborators was fanning the first flames of revolution. Huppert’s mother is a former schoolteacher from France who moved to Cambodia 20 years earlier with her civil-servant husband. She bore him two children, virile 19-year-old Joseph (Ulliel) and beautiful tease Suzanne (Berges-Frisbey), 16, neither of whom has ever been out of the country. The paddies that so determined the fate of the peasants in Rice People perform a similar function here, though in The Sea Wall the lives of both colonists and indigenous peasants are determined by the condition of the fields. In the latter film, a weak sea barrier collapses regularly, allowing salt water to flood and ruin the new crop. Like the rice itself, the mother is slowly dying from the whims of nature and from the incompetence and blatant corruption of the French bureaucrats she is unafraid to confront. She also tries to organize the Cambodians so that they will strengthen the wall and refuse to give up their land.

An extremely wealthy son of a Chinese capitalist, Monsier Jo (Douc), arrives not on a shiny white horse but in a shiny new luxury car. He becomes obsessed with Suzanne, whom he impresses by showering her with expensive gifts. Her mom, worried about losing her land, and even her racist brother are not above pushing her into marriage for money. Yet this handsome man, who at first appears merely a spoiled dandy, turns out to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. In collusion with the French, he uproots the locals from their land, burning their homes and treating like criminals on a chain-gang march. The dying mother correctly predicts that one day the children of her devoted Cambodian servant, nicknamed Colonel (Vathon), will rise up against their European overlords.

For more on the films of Rithy Panh, click here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home