Enduring symbol

The post office in all its glory, including its wings which were added after its original construction

The post office in all its glory, including its wings which were added after its original constructionLabels: The Heritage Mission

Cambodia - Temples, Books, Films and ruminations...

The post office in all its glory, including its wings which were added after its original construction

The post office in all its glory, including its wings which were added after its original constructionLabels: The Heritage Mission

The Heritage Mission presentation warned against the loss of colonial architecture like this building that has since disappeared from Norodom Boulevard in the past year

The Heritage Mission presentation warned against the loss of colonial architecture like this building that has since disappeared from Norodom Boulevard in the past yearLabels: The Heritage Mission

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Hun Sen

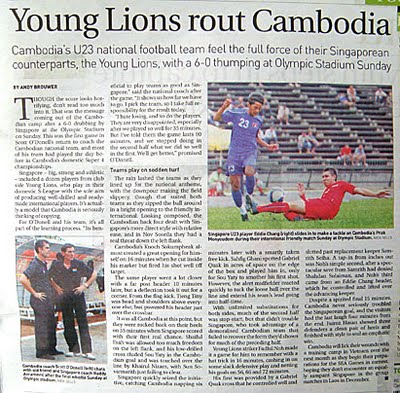

Today's Phnom Penh Post carries my report on the international football friendly between Cambodia and Singapore, played on Sunday. It's online here.

Today's Phnom Penh Post carries my report on the international football friendly between Cambodia and Singapore, played on Sunday. It's online here.Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Today's Phnom Penh Post carries my match reports from the Cambodian Premier League Super 4 deciders on Saturday. Read them online here.

Today's Phnom Penh Post carries my match reports from the Cambodian Premier League Super 4 deciders on Saturday. Read them online here.

Naga celebrate reaching the CPL Super 4 final and I'm merely trying to get a good photo. Rumours that moments before I was sitting on the bench are untrue.

Naga celebrate reaching the CPL Super 4 final and I'm merely trying to get a good photo. Rumours that moments before I was sitting on the bench are untrue. Okay, so I'm sitting on the bench but it was momentary whilst I congratulate Naga skipper Om Thavrak on another blood and guts performance by the CPL's hardman

Okay, so I'm sitting on the bench but it was momentary whilst I congratulate Naga skipper Om Thavrak on another blood and guts performance by the CPL's hardmanLabels: Naga Corp, Om Thavrak

Meas Soksophea entered the ring a couple of times to sing two songs. She really does have a lovely voice. More Soksophea, less boxing please!

Meas Soksophea entered the ring a couple of times to sing two songs. She really does have a lovely voice. More Soksophea, less boxing please!Labels: Meas Soksophea, Nuon Soriya, TV3

The Cambodian U23 starting line-up for the Singapore friendly. LtoR (back row): Sovannarith, Tiny, Yaty, Narong, Rady, Rithy. (front row): Kumpheak, Sokngorn, Soseila, Sokumpheak, Sothearath.

The Cambodian U23 starting line-up for the Singapore friendly. LtoR (back row): Sovannarith, Tiny, Yaty, Narong, Rady, Rithy. (front row): Kumpheak, Sokngorn, Soseila, Sokumpheak, Sothearath. Sun Sovannarith (blue) captains the national team against Singapore (red). The referee was Thong Chankethya.

Sun Sovannarith (blue) captains the national team against Singapore (red). The referee was Thong Chankethya.Labels: Cambodia U-23s

A downpour greeted the teams arrival on the pitch before the national anthems and presentation to the VIP guests

A downpour greeted the teams arrival on the pitch before the national anthems and presentation to the VIP guestsLabels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Scott O'Donell

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Meas Soksophea

Phnom Penh Crown (red) have already left the pitch and Preah Khan (blue) are not allowed to play on by the referee

Phnom Penh Crown (red) have already left the pitch and Preah Khan (blue) are not allowed to play on by the referee The Preah Khan management and players argue with the match officials that the 3rd goal should've stood

The Preah Khan management and players argue with the match officials that the 3rd goal should've stood The referee and his assistants with their security detail as they come out for the 2nd half, at last

The referee and his assistants with their security detail as they come out for the 2nd half, at lastLabels: Cambodian Premier League

The golden boot winner with 21 goals, Uche Prince Justine from Spark FC, winner of a 2 million riel reward

The golden boot winner with 21 goals, Uche Prince Justine from Spark FC, winner of a 2 million riel reward The top VIP was the Minister of Tourism HE Thong Khon (in white), who's also head of the Cambodian Olympic Committee

The top VIP was the Minister of Tourism HE Thong Khon (in white), who's also head of the Cambodian Olympic CommitteeLabels: Cambodian Premier League

The Nigerian trio of Yemi Oyewole, Friday Nwakuna and Sunday Okonkwo celebrate their CPL Super 4 success

The Nigerian trio of Yemi Oyewole, Friday Nwakuna and Sunday Okonkwo celebrate their CPL Super 4 successLabels: Cambodian Premier League, Naga Corp, Sunday Okonkwo

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Naga Corp, Om Thavrak

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Naga Corp, Om Thavrak

Follow the Mekong - with time to watch the ebb and flow of a river's life, Graham Reilly floats from Vietnam to Cambodia (Brisbane Times, Australia).

I stare from the riverbank at this astonishingly vast and lively world of water. Here, in the charming provincial city of Can Tho in the heart of southern Vietnam's Mekong Delta, it is as if the land is merely an afterthought. Everything is about the river and the way of life it sustains. It is a world of colour and movement, of a comforting spray of cool water on your face as you are rowed back to your hotel at night in a slim stick of a boat, of the sleepy glint of dusk as you trail your finger across the river's surface, of the cough and splutter of a small passenger ferry as it crosses the river to Vinh Long, of the throaty gurgle of a rice boat as it slowly motors to Ho Chi Minh City or Cambodia.

The Mekong begins its 4500-kilometre journey to the sea in Tibet and winds its way through China, Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and finally into the Mekong Delta. The Vietnamese call the river Cuu Long, or nine dragons, and it is easy to see why, for here the Mekong spreads in great tentacles into nine exits to the sea. Can Tho sits on the banks of one of these tributaries, the Hang Giang river, also known as the Bassac, an impossibly broad, bustling expanse of brown water. It is a pleasant capital of 300,000 people, with tree-lined boulevards, cool grassy squares and 19th-century buildings that are remnants of French colonial days. One of the great pleasures of Vietnamese provincial towns such as Hoi An or Nha Trang is the local markets and Can Tho is no exception.

Selling vegetables, fruit and seafood, its large market spreads over an entire city block on one side and follows the curve of the river on the other. There is much to do here and it is a good place to organise a home stay with a farming family. It is also a good place to do nothing much at all. Gazing out from the pleasant promenade, I see boats of all shapes and sizes, one of which takes my friends and I early next morning to the famous Cai Rang floating market. Boats from all over the region – from Bac Lieu, Vinh Long and Camau – come here to sell what seems like every fruit and vegetable ever imagined: jackfruit, oranges, rambutan, bananas, longans, pineapples and sweet potatoes.

An, 30, is our guide. It is her father's boat and her husband navigates it safely through the shifting mass of craft on the river. "He is a good husband," she says, smiling. "He is happy to cooking and washing with me at night." We nod in agreement. A good husband can be hard to find. I explain to her that we want to travel to Cambodia by boat, from Can Tho to Chau Doc, across the border and up to the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, and then on to Siem Reap, home of one of the great wonders of the world, the temple complex of Angkor Wat. We've got six days for the journey of more than 400 kilometres. An offers to arrange the journey and a few phone calls later we agree to meet at the Can Tho dock at 2pm the next day. I tell her I have visited these places before but always by road or air. This time I want a gentler, more romantic mode of transport along the mighty Mekong and its tributaries. I want to hear the gentle slap of the water against the boat, feel the tropical breeze on my skin and watch people go about their lives on the riverbanks. I want to be part of the landscape. I want to make the journey as important as the arrival.

Can Tho has several restaurants along the waterfront and that night we decide on the Thien Hoa. We settle happily at a pavement table in the evening balm, show no restraint and order a feast – fried snake with onions, sea bass soup with tamarind, prawns steamed in beer, catfish hotpot and coconut ice-cream. It is a meal to remember and a harbinger of culinary experiences to come. Loaded up with fruit and sandwiches we've borrowed from the sumptuous breakfast buffet at the Victoria Hotel, we board the "fast boat" to Chau Doc, a journey An tells us will take about three hours. She says the slow boat, which leaves at 6.30am, takes about eight hours.

The fast boat is a long, relatively sleek, metal-hulled craft that does not go particularly fast, which turns out to be a blessing, given the pleasure of being on the water and lounging on the deck and watching the world go by. Most of the passengers are part of a package run by Delta Adventure Tours that includes a night at the company's floating hotel in Chau Doc. As we are travelling independently, we each pay $US20 ($23) for the trip. The boat seats about 30 people in something more or less resembling comfort. Sitting on the deck munching on a bag of rambutan, it becomes immediately clear to me that this is a working river. Large boats, washing fluttering in the breeze and overloaded with bananas, take their produce to market. Other boats dredge silt from the riverbed to be used in the construction industry. The weight of their cargo lays them so low in the water it is as if just one more grain could tip them into the muddy depths.

The riverbanks jump with activity. A line of brick kilns several kilometres long puffs smoke as families stack freshly baked bricks or load them on to waiting boats, the children straining under the burden. The smell of fermenting fish sauce wafts from factories onshore. Much of the riverbank is lined with sandbags to protect stilted houses from the river, which swells dramatically during the wet season. There is so much of interest to observe on the water and the riverbanks that the journey passes quickly and before I know it we are approaching Chau Doc, a journey of 5 hours. The river seems to settle in the dusk and takes on a kind of dreamy indolence, as if it has done enough work for the day. Meanwhile, I have been lulled into a sense of well-being I've never experienced when travelling by road or air.

Impressed with our stay at the Victoria Hotel in Can Tho, we decide to spend a few nights at the Victoria in Chau Doc. It is another elegant, splendidly positioned, colonial-style building perched on the banks of the Bassac. The view from our room across the spreading river takes my breath away. Chau Doc shuts down early and we are lucky to get to the Bay Bong restaurant while it is still serving dinner. The restaurant forgoes interesting decor for delicious Mekong cuisine. It's another feast. We start with canh chua, the local sweet-and-sour fish soup, and follow this with steamed fish and prawns, including ca kho, stewed fish in a clay pot. It's so good we return the next night. Chau Doc is another attractive and welcoming provincial town of about 100,000 people with an enormous market that snakes along the riverfront. The fish section alone – which has not just fresh fish but dried, spiced, marinated and salted – is wondrous.

We're close to the Cambodian border here and the people are more obviously Khmer, with their fuller features, darker skin and a preference for a chequered scarf over the ubiquitous Vietnamese conical hat. It is also home to a sizeable community of Chams, a Muslim minority of Malaysian appearance who live on the other side of the Bassac river. We hire a boat and motor across to the Cham village. On the main street, dotted with stalls selling fruit and vegetables and snacks, women chat in the shade of the verandas of their wooden houses. Little girls sell waffles and simple cakes to visitors. I meet the caretaker of one of the two mosques. He shows us a short film about the history of the Cham but it is in Vietnamese so we leave none the wiser. This part of the Bassac river, where it meets the Mekong, is home to an extraordinary concentration of floating houses, each of which is a self-contained fish farm. In the centre of each house is a large cage submerged in the river, in which families raise local bassa catfish, thousands of tonnes of which are exported to Australia every year. The fish are fed a kind of meal made from cereal, fish and vegetable scraps in cauldrons that rumble and roil. The smell is challenging.

At eight the next morning, we board another fast boat for the journey to the Cambodian capital. On another steamy, insanely hot day, we are looking forward to spending the trip on the deck, savouring the breeze. But a gaggle of young American backpackers with newsreader voices storm the boat and secure the outdoor area as their headquarters. It is their world. We just live in it. As we travel towards Cambodia, the river begins to change. Gone is the frenetic boat activity and on the riverbank life takes on a less industrial, more bucolic demeanour. As we rejoin the Mekong, the river widens and soon the factories on the shore are replaced by cornfields, banana trees that shift and flap in the breeze and ragged, palm-thatched huts. Families bathe in the shallows and children scrub and splash their wallowing buffaloes. One-and-a-half hours later, when we reach the border at Vinh Xuong, Vietnam, and Kaam Samnor, Cambodia, we're in a different, more lush, more languid world.

We disembark at the border post and after an hour or so filling in various forms and questionnaires, we say goodbye to the Vietnamese boat and board the altogether less salubrious Cambodian craft for the rest of the journey. But in the end the boat's state of rugged disrepair matters little and most people spend the afternoon sitting on the rear deck or lounging on the bow and impairing the vision of the driver. It is all too idyllic and, as it turn out, too good to last. Low water levels in the Tonle Sap river mean we have to complete the final leg of the journey by bus. But even this is fascinating, if cramped, as we hurl through the countryside and the sedate outskirts of Phnom Penh. As we arrive in the busy heart of the capital, I check my watch. It was just over seven hours ago that we boarded the boat in Chau Doc.

At our hotel, the owner tells us the water levels in the Tonle Sap are too low for us to go by boat to Siem Reap and that we'll have to take the bus or fly. He dismisses our disappointment, saying the boat has a karaoke machine on board. "Very noisy." But we won't decide what to do until after dinner – perhaps some steamed fish in coconut milk or fried squid with green peppers. As we hop into a tuk-tuk to take us to the waterfront, a young girl, brown as a nut and cute as a button, implores us to buy some bottled water. "What's your name?" I ask. "Cosmic," she replies, beaming. "Where are you from?" "Australia." "Do you know Kevin Rudd?" she asks. "Of course." "Well, he is my father." I look puzzled and she giggles. We are smitten and it's bottled water all round. As we putter away, she yells to us: "Tell Kevin his daughter says hello." I wave and promise I will.

Labels: Mekong River

Decades of slow and unreliable train service prompted Cambodians to make their own use of the tracks and hundreds of illegal “bamboo trains” now run along the single-lane, 596km-line, that begins near the Thai border in north-west Cambodia, extends east through Battambang to Phnom Penh, then runs south to the coastal port of Sihanoukville. “There’s only one in the whole world,” a Battambang tour guide, known as Tap Tin Tin says, while escorting a Dutch family of five along the bamboo railway. “You see it transporting tourists, but it’s very useful for the Cambodians to carry rice or bring a cow or pig to slaughter in town.” In Battambang about 100 tourists ride the cars daily, and hotels and tour guides all advertise rides on the renegade railway. Soon, however, their voyages along Cambodia’s makeshift railroad will end. An ongoing, five-year, US$148 million railway project aims to reclaim Cambodia’s tracks from disrepair and connect them to Singapore. De-mining and emergency repair work began in early 2008, and new tracks are expected to go down in November, according to Nida Ouk, an official with the Asian Development Bank, the project’s primary donor. In July, an Australian company, Toll Group, signed a concession to manage Cambodia’s rails. In addition to increasing freight traffic and quadrupling current train speeds, Ouk says that the project’s funders plan to enforce the ban on the illegal bamboo cars, citing safety concerns and promising to provide alternative skills training to those who operate them. “You can imagine, it could cause a major traffic accident,” he says.

As we speed toward the opposing car, my 19-year-old driver, Soung Vy, and his co-conductor, Vat Vy, 16, sit calmly atop the platform’s rear railing. Each has a pierced ear – Vat also has nose, lip and tongue piercings. Soung lifts his leg off our five-horsepower engine and pushes his foot down on a piece of wood suspended above the wheels to stop us from running into the car loaded with rice farmers. Five people sit on our cart, compared to 17 on the opposing cart, so we are obligated to disassemble and allow the other to pass. When opposing cars hold equal loads, drivers decide who disembarks with a game of rock, paper, scissors. We deboard. Soung and Vat grudgingly walk to either side of our platform. They easily pick it up and set it in the brush. Each then lifts a set of wheels, hoisting the axle like a barbell, and sets it aside.

On the other car, Duk Kun, 40, is waiting to go home after a long day planting rice seeds on his one-hectare plot of land. He wears a cowboy hat and smokes a cigarette. Because his field is 15km from the nearest paved road, he rides the bamboo train every day during planting and harvesting season. Without it, he says, he would walk two hours to work. Beside him sits 10-year-old Ho Makara, riding home after visiting relatives down the line. Their driver winds a rope tightly around the motor and pull-starts the engine. As they accelerate away, Soung and Vat reassemble our car. Soung climbs aboard the rear railing and wraps a fan belt over a motor gear – the other end of the belt is already looped around the axle through a hole in the bamboo platform. He pull-starts the engine and we’re off. The breeze cuts the humidity and clouds of multicoloured butterflies flutter past.

I had wanted to ride a real train, but when I arrived at the stately old colonial station in Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, I found the gates locked. The landmark building last filled its atrium corridors when a nightclub hosted a dance party there earlier this year. The afternoon I visited, a few squatters slept on the floor. Ouk Ourk, an official with the Royal Railways of Cambodia, told me that passenger services stopped last year because of the poor state of the tracks. Freight trains derail occasionally, he said, and petrol cars have tipped and spilt. “We were worried about derailment, about someone dying – we haven’t had this, but we wanted to prevent accidents,” he said. Behind his office at the Phnom Penh station sat dozens of abandoned freight cars and several abandoned passenger cars. Holes dotted the floors and ceiling, broken seats rested in piles, and mounds of human faeces were scattered on the floor, vestiges from the poor who now live in the cars. Freight trains leave for Battambang about once a week and eke along the tracks at 10 to 20km-per-hour, said Ouk Ourk, creeping at a pace that gives bamboo operators adequate time to get out of the way or attempt to outrun it.

Ouk Ourk said the only way civilians ride the tracks is on a bamboo cart, and the best place to do it is in Battambang. Five days later, I arrived at the main train station in Battambang, another decaying colonial building and reminder of Cambodia’s history as a protectorate from 1863 to 1954 of the French, who built these tracks and buildings in the 1930s. Once again, the doors were locked. A dozen children, aged two to 12, sat on the station’s windowsills and slid their flip-flops along the floor in a rudimentary game of marbles. Cows grazed beside the rails. Two volleyball nets were strung on grassy patches between the tracks. As I waited for a bamboo train to pick me up, my guide and translator, Thy Racky, 36, got a call from our driver saying police would not let him enter town. Operators are forbidden from entering inner-city stations, although we’d convinced our driver to attempt to sneak in. Instead, a tourist’s trip along the rail starts about four kilometres outside Battambang town, at the end of a winding dirt road in O Dambong village. Bamboo platforms are stacked on the ground outside another abandoned train station. A young man sells bubble tea for $0.25 from a mobile cart out front.There is no ticket counter. Taped to the back of the building’s door is a piece of paper listing the names of train operators who share business on a rotating schedule. Cambodians pay about 25 cents for a one-way ride while foreigners pay about $10 for a trip 10km up the line to O Sra Lav village and back. One traveller, 60-year-old Vive Armstrong from New Zealand, boarded a bamboo train without hesitation. “It looks smoother than the roads,” she said, referring to Cambodia’s notoriously bumpy streets. After we let the horde of day labourers pass, I am seated cross-legged with two other passengers as we thump over the warped tracks. An emaciated cow occasionally meanders over the tracks. Looking down as we cross a river I see pieces of cement missing from the 80-year-old bridge. I clench my jaw as we jump gaps in the tracks that are six centimetres long. I ask my guide, Thy Racky, if anyone is ever injured. He says six tourists were hospitalised last year when their bamboo train hit a bump and flipped off its wheels.

Railway officials have long utilised similar carts, but without engines, to inspect the tracks. Civilians began using the carts in the early 1980s after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, the radical communist regime that killed some 1.5 million Cambodians and left the country’s economy and infrastructure in disrepair. Our bamboo train slows to a stop at O Sra Lav station, where I meet Pat Oun, 69. He owns a beverage shop catering to tourists, but he also says he built 200 engineless lorries before packing up his chisel and axe in 1983. Each took about four days’ labour, he says. In those days, the operator pushed the cars forward with two long oars – like a gondolier. In 1992, according to local lore, a man named Mr Rit, now deceased, strapped an irrigation pump engine on the cart, creating the first motor-powered bamboo car. “Everyone just thought a bamboo train would be very useful to transport things from here to there,” says Pat Oun. Today, a bamboo train sells for about $600, he says. The platform and engine each cost about $200, and the wheels, salvaged from the gears of old bulldozers and army tanks, cost about $180. About 200 bamboo train operators work the tracks near Battambang, with hundreds more toward Phnom Penh and near the coast. Operators tell me that bamboo cars can travel the 338km distance from Battambang to Phnom Penh in 13 hours, several hours faster than the journey by passenger train before service was discontinued. Back in Battambang town that night, while indulging in one of the famous fruit shakes at the White Rose restaurant, I meet Willem Bierens de Haan, a 25-year-old from the Netherlands. Earlier in the day, I saw him and his girlfriend whizz past me on a bamboo train, grinning wildly. “We wanted to experience how the locals make use of the unused rails,” Willem says. “It’s like a roller coaster through the countryside.”

The chronology of Roy's musical career is well-documented on his Myspace and my intention was to try and find out more about Roy himself, both in and away from his involvement in music. After a little chit-chat and a lot of gossip we got down to the business of discussing Roy's childhood. He was one of three brothers born in the small market town of Ledbury, Herefordshire, and described the intense claustrophobia he felt growing up where everyone knew everyone else's business. (His mother was one of nine children, most of whom stayed in Ledbury).

Roy described his paternal grandfather as a hard-boozing bully, whose family had lived in fear of his drunken rages. Roy's own father was the exception amongst his brothers in being a gentle non-drinking man who considered some of the happiest days of his life to have been in WWII. The RAF had given him his first taste of life away from his cruel father (who incidentally ended his turbulent days by blasting his own brains out with a shotgun, whilst in an outside toilet). During Roy's growing years his dad earned well as a Jag-driving bricklayer in post-war Britain's building boom. The family home had previously been part of a Prisoner of War camp building, divided into two halves to become council houses. Roy laughed at the irony of the returning war heroes' reward. Despite less than palatial surroundings, Roy's family enjoyed a good standard of living and his dad seemed determined to give his own sons a happier start in life than he had known. His love of music including Buddy Holly and The Everly Brothers rubbed off on young Roy, and when he first showed an interest in learning an instrument, aged nine, his dad bought his first guitar.

Grammar school years soon followed, which Roy detested for a variety of reasons, one being the painfully obvious class awareness which existed among both pupils and staff. He was the only child amongst his peers who had passed the 11+ exam so while his mates carried on kicking a football about together at the local comprehensive, he endured a stuffy grammar school life. Stifling rules (such as not being allowed to take his cap off on the way to and from school) led to his earliest memories of wanting to rebel. Roy described his continuing admiration for an older boy who defiantly wore winklepicker shoes to the school. His final school report noted he was 'far too interested in pop music to achieve satisfactory academic qualifications'.

Having had enough of formal eduation and with three whole "O" levels to his name (English Literature, English Language and Art) at fifteen he hit the big wide world with a running jump as an estimating clerk for a company which made envelopes in Ledbury. However, that occupation may well have provided the break which led to the Roy we know and love, for a day-trip to London arranged by the company had an enormous impact on the young lad. The trip had been arranged to watch a Miss World competition at the Lyceum Ballroom in The Strand, and having tired of watching beauty after beauty on parade he sneaked out of the building for his first ever taste of London. It was 1966, he saw streets full of hippies ("Ledbury didn't have one"), exciting places he had only read about such as The Marquee, prostitutes, and the full range of sights and sounds of swinging London. The experience ("and my first feeling of anonymity") had a profound effect on Roy.

One of Roy's earliest memories of attending a live gig stems from when he watched King Crimson supporting Black Sabbath in Malvern; the excitement of the occasion was obviously flooding back as he recalled Robert Fripp and the magic of "21sth Century Schizoid Man" live. However, Roy described THE defining moment in his desire to be part of the music industry to have occurred whilst watching The Who perform in 1966, also at Malvern Winter Gardens. Awestricken, he watched Pete Townsend, resplendent in his Union Jack jacket. To Roy his angry performance seemed to scream "London!", and he knew his Ledbury days were numbered.

His relocation to the bright lights came when he was 18, and had been studying at Hereford Art School. His girlfriend of the time (they married when he was 21) took up a teaching post in Charlton, and he moved in with her. Chrissie (now his ex, with whom he and his partner Celia are great friends), exposed Roy to greater musical variety than he had known previously. Whereas he had mainly collected records by mainstream artists such as The Beatles, The Stones, The Kinks and The Who, her collection included singer-songwriters such as Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, the latter of whom struck a particular chord with Roy. After a while, and following a job offer in Cirencester (Roy was working in advertising agencies at the time), the couple moved to Cheltenham. Roy began writing his own songs and playing occasional gigs from around 1971-74 in local folk clubs. It wasn't that he played folk, but where else was a singer with an acoustic guitar to play? Roy found the clubs friendly places, where the majority of audiences were happy to hear something a little different. Whilst playing the clubs he became friendly with various local musicians including Dik Cadbury, Phil Beer, Bimbo Acock (later sax player in Roy's band) and Bimbo's brother John, who worked as a studio engineer at the De Lane Lea Studios, Wembley. This fortuitous friendship led Roy back to London for the occasional session of free studio time.During this era Roy often put together bands which were as fluid as his performances, sometimes consisting of three, four or maybe five musicians. It all depended who was free at the time, and just as now, Roy revelled in spontaneity in his performances. He was writing songs prolifically ("George's Bar" was one creation of the time), and described how he would "bash out" song after song in a whirlwind of creativity. "Falling" was written, from start to finish, during a walk down Oxford Street. Roy's songs have often been characterised by lyrics which tell dark tales set to jaunty tunes which would generally be considered completely mismatched. That inability (or refusal) to "fit the mould" is part of Roy's unique fascination. His performances are often riotous, with his offbeat sense of humour having audiences doubled up with laughter and often wondering what will happen next. Roy told me his inclusion of humour (his own brand – be warned!) onstage happened in a very unplanned way. The Roy Hill Band was playing at Bradford University one night in 1978, it was dark, and Roy went flying as he tripped over an electricity cable while walking onstage. The audience laughed and Bimbo was close to hysterics. Roy realised instantly how humour had built good communication with those watching, and making people laugh was set to stay. Roy also recounted that when he later began playing as half of a duo with Chas Cronk he found noisy audiences in West London pubs very difficult to capture. By becoming "Mr. Pottymouth" with an inflated persona, Roy was able to grab punters' attention and get them to listen to the music. "The survival instinct", he mused.

Almost inevitably our conversation touched on how he had often managed quite spectacularly to be in the "wrong place at the wrong time" in his career. For instance, Roy's first album was produced by Gus Dudgeon, best-known for his work with Elton John. This "lucky break" unfortunately coincided with punk's overthrow of the existing music establishment, and Roy feels his songs would have better suited production in the style of Elvis Costello and his contemporaries rather than Gus's love affair with orchestration. Certainly, Roy's "handsome hunk" (my interpretation, not his!) album sleeve did not sit well in record racks next to covers adorned with scowling, emaciated punks with safety pins through their noses. Roy laughed about a time when he was working at Wessex Studios in North London and watched the Sex Pistols' publicity machine in action. The Pistols were to be photographed "gobbing" at kids going into the school opposite, and he laughed as he recalled how "set up" the whole episode had been, with the "gobbing" starting on cue as the cameras rolled. Roy recounted numerous interesting tales of his music business career, including the time he recorded a song called "When Love is Not Enough" with Roger Daltrey at Olympic Studios in Barnes. Daltrey had a couple of minders with him, but Daltrey was himself the "scary" figure at the time according to Roy.

Like most musicians, Roy has suffered his share of demoralising"bad press", and recalled one painful article which appeared in the music press headed "Hill Scores Nil". However, following subsequent good reviews written by highly credible journos Tony Parsons and Julie Burchill, sheep-like music journalists changed their tune overnight to sing his praises. Roy is well aware of the fickle ways of the music industry; a week after parting ways with Jim Beach (simultaneous manager of himself and the mighty Queen) he found himself selling massage machines in Norwich. As you may have already guessed, Roy is refreshingly willing to talk about his life and career, warts and all. He readily admits that in the past he must have proved very difficult to work with, and only half-jokingly declared that he has walked out on himself several times while working on his current project.

That project is an as yet unfinished album entitled Switzerland. Roy told me that until now he'd had zero interest in the technical aspects of music-making, and in the past, such as when Cry No More recorded at their makeshift studio in Kingston, Chas was left with sole responsibility for all things technical. Roy simply went along, sang and played, and left Chas to it. The creation of Switzerland, where Roy has been responsible for entirely everything, has therefore proved an enormous learning curve. The recordings are not perfect, ("you can hear the fridge door shutting, Celia walking into the room and stuff like that") but Roy relishes being in complete control of everything that happens to the recordings from start to finish. He has felt dissatisfied with everything he has recorded in the past due mainly to overproduction. Happy to admit to having a perfectionist streak, Roy feels with Switzerland he hopes to create an album which 'within the limitations of doing everything myself' he is happy in all respects. However, Roy declared that he would never again attempt to create a CD from start to finish completely unaided, as the project has sometimes felt like an endless and exhausting task.

Work on Switzerland continues. Having unknowingly been suffering from depression while writing the songs, he almost feels as though they seem to belong to someone else. Lyrically they have not been altered, but Roy has been fine-tuning them musically. For him, the adventure into instrumental pieces lasting up to four minutes ("not quite prog, but for me it is") is uncharted territory. He has taught himself to play piano pieces in a way which fit the music precisely as he wants. Roy feels that with Switzerland he has finally bared his soul rather than masking bleakness, and he is obviously uncertain how it will be received with its references to sombre topics such as death and mortality.

Lest anyone should reach the conclusion that my time with Roy was all doom and gloom, I would like to point out that it very definitely wasn't. Roy is engaging, amusing, very open, and someone I would be happy to chat with for hours. As I did! Remembering a list of questions which had been sent by members of the Witchwood discussion group, several of particular interest to Strawbs' fans, I finished up by firing the questions at Roy which he obligingly answered:

Q: How did you come to support Strawbs on their "Deadlines" tour? A: "I performed "George's Bar" acoustically on a tv programme called "So it Goes", which featured other artists including Elvis Costello and Iggy Pop. Dave Cousins saw the programme and invited me to support Strawbs on tour. That was a lot of fun. Dave was very supportive and I instantly hit it off with Chas Cronk and Tony Fernandez, both of whom later joined my band. The experience was very different from when my band toured as support to Styx, who refused to let us play one night just because there was a tiny buzz coming from one of their amps."

Roy elaborated that following "personnel issues" in his band which left him needing a bassist and drummer, John Cooper, General Manager of Arista Records, had suggested approaching Chas and Tony to join. Roy's reaction was to wonder why on earth they would want to join his band, but they did ("bringing 'good humour and professionalism' with them"). Two tours and numerous London gigs followed, after which they lost touch. Roy later rang Chas (whom he considers a "superb and highly intuitive bass player"), a duo gig was arranged at The Mulberry Tree pub in Twickenham, and they began writing songs together. Their writing generally consisted of Chas supplying the chords, to which Roy added a tune and lyrics.

Q: Were you a Strawbs fan before you toured with them? A: "I knew of them by reputation. I was a bit shocked when I heard them on the tour though. I had been expecting more of a folk group than a full-on rock band."

Q: How did you come to take over as Strawbs' lead singer for a couple of gigs? A: "I was asked to fill in after Dave had left to fulfil contractual obligations which Strawbs had. The gigs were a bit of a mish-mash where no-one (including the band) really knew what to expect, and we played a mixture of my own songs and Strawbs' songs. Strawbs without Dave Cousins doesn't really make much sense does it? Strawbs with me made even less."

Q: Where did the name "Cry no More" come from? A: "I wrote a song called "Cry no More" and we put it out as a single in a homemade cover with "Cry no More" printed on it using a lino cut. After I'd printed the song title I realised there was not enough room for a band name as well, so the band took on the name."Q: What music do you listen to? A: "Loads! A lot of Dylan, Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell and Randy Newman. I listen to classical music; Chopin, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Mahler, Bach. Some jazz; Miles Davies, Bill Evans, Django Reinhardt, Oscar Peterson. Sixties stuff. Judy Garland, Edith Piaf, Dean Martin. My son Jamie keeps me up to date with the modern world. 'You've got to hear this dad …!'"

Q: What inspires you to write music? A: "I have a need to write things down. It's like keeping a diary but my diary is full of songs and stories. I have no idea where the tunes come from. The words are drawn from personal experiences and observations, chance remarks, a view from a train, a line in a film, rain, barking dogs, cuckoo clocks, murder …"

Q: Has anyone ever covered one of your songs? A: "Yes, Buck's Fizz covered "Tears on the Ballroom Floor". You have to hear it."

Q: Do you have any hobbies apart from music? A: "People-watching, travelling, reading (current book: "London: The Biography" by Peter Ackroyd) and art galleries. I like painters who use their own language; Kandinsky, Klee, Mondrian." (Roy and I had initially intended to visit the Tate Modern, but never made it - I suspect we would have been thrown out for talking too much anyway.)

Q: Do you prefer working as a solo musician, as part of a duo, or with a band? A: "Solo. It's not that I don't enjoy playing as a duo or with a band, but working as a solo artist means I don't need to make any compromises or fit in with anyone else, either while writing or onstage. It is more scary to play solo as there is no-one else to exchange glances with if anything goes wrong, and everything is down to me. I often get very nervous before playing, even being sick, the feeling is similar to standing in line waiting to go on a giant roller-coaster, a mixture of wanting to do it and being terrified. Once you're strapped in though, 'Yahoo!' Playing solo is the ultimate adrenalin rush."

Q: Do you have any solo gigs lined up? A: "Yes, my 2009 World Tour takes place at The Open House Café, in Brentford on 25th September." After well over five hours and several cappucinos in various South Bank locations, Roy and I parted company. I am looking forward immensely to seeing him perform at The Open Café on 25th September. For more details, to check on the progress of Switzerland, or to venture into Roy's blog, visit his MySpace.

Labels: Roy Hill

The guy sat down and looking interested, is me at this morning's press conference, caught on camera on CTN

The guy sat down and looking interested, is me at this morning's press conference, caught on camera on CTN Labels: Cambodia U-23s

This is my article on Sunday's match between Cambodia Under-23s versus Singapore Under-23s at the Olympic Stadium that appeared in yesterday's Phnom Penh Post. You can read the article online here.

This is my article on Sunday's match between Cambodia Under-23s versus Singapore Under-23s at the Olympic Stadium that appeared in yesterday's Phnom Penh Post. You can read the article online here.Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Phnom Penh Post, Scott O'Donell

23 of the 25-man Cambodia Under-23 squad line up with the coaching staff after this morning's press conference

23 of the 25-man Cambodia Under-23 squad line up with the coaching staff after this morning's press conference  The national team's coaching staff. LtoR: Bouy Dary, Van Piseth, Scott O'Donell (coach) and Prak Sovanny

The national team's coaching staff. LtoR: Bouy Dary, Van Piseth, Scott O'Donell (coach) and Prak Sovanny The top table at the press conference. LtoR: Van Piseth, Scott O'Donell, Ouk Sethycheat (gen sec), Vann Ly (team manager).

The top table at the press conference. LtoR: Van Piseth, Scott O'Donell, Ouk Sethycheat (gen sec), Vann Ly (team manager).Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Scott O'Donell

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Scott O'Donell

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Scott O'Donell, SEA Games

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, RV La Marguerite, Scott O'Donell

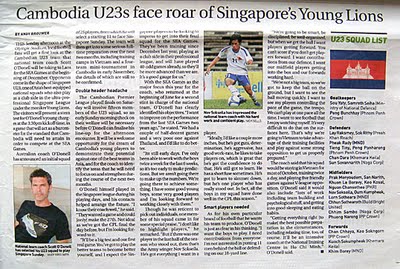

Sophoin points to her favourite de Vries photo, which she says shows the strength of the Cambodian soldiers defending Preah Vihear

Sophoin points to her favourite de Vries photo, which she says shows the strength of the Cambodian soldiers defending Preah Vihear Two of the Preah Vihear soldiers pass the time. Now recognised the soldier getting his hair cut as coming from Siem Reap.

Two of the Preah Vihear soldiers pass the time. Now recognised the soldier getting his hair cut as coming from Siem Reap.Labels: Eric de Vries, Now, Sophoin

Labels: 4Faces, Eric de Vries, Vann Nath

Another pose against a backdrop that is typically Cambodian

Another pose against a backdrop that is typically Cambodian Nick, the biker, doing his best to splash as much mud on himself as possible

Nick, the biker, doing his best to splash as much mud on himself as possibleLabels: Blazing Trails

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, On Trial

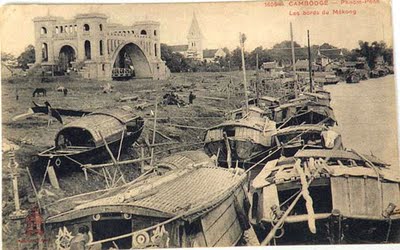

Labels: Pont de Verneville, The Heritage Mission

The glorious Pont de Verneville, constructed at the turn of the century, but demolished just 30 years later

The glorious Pont de Verneville, constructed at the turn of the century, but demolished just 30 years later A 1930 ariel view of the de Verneville Bridge (white) and the Tonle Sap River, just before the bridge was demolished and the canal filled in

A 1930 ariel view of the de Verneville Bridge (white) and the Tonle Sap River, just before the bridge was demolished and the canal filled inLabels: Pont de Verneville, The Heritage Mission

The Treasury was built at the behest of the Resident Superieur Huyn de Verneville. The Khmer wording says General Department of National Treasury.

The Treasury was built at the behest of the Resident Superieur Huyn de Verneville. The Khmer wording says General Department of National Treasury. Though obstructed by trees, this is the former Bank of Indochina, built in 1893 and now housing Van's Restaurant

Though obstructed by trees, this is the former Bank of Indochina, built in 1893 and now housing Van's RestaurantLabels: The Heritage Mission

Labels: The Heritage Mission

Labels: Chinese House, Eric de Vries

The southern section of the eat gallery which is out-of-bounds until next year. You can see where the water seepage effects the lighter stonework.

The southern section of the eat gallery which is out-of-bounds until next year. You can see where the water seepage effects the lighter stonework.Labels: Angkor Wat, Churning of the Sea of Milk

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, Cambodian Premier League

Labels: Shadow of Angkor, Tara Angkor, The Sothea

Labels: Angkor, Cambodian Premier League, Phnom Penh Post

Now proudly displays her own photographs for sale at the 4Faces Gallery, where she works with my pal Eric de Vries

Now proudly displays her own photographs for sale at the 4Faces Gallery, where she works with my pal Eric de Vries We set up our Hanuman safari tent at the secluded Ta Nei temple and this is the dining table arrangement

We set up our Hanuman safari tent at the secluded Ta Nei temple and this is the dining table arrangement This week is a very important time for Buddhists in Cambodia, so the shrines within The Bayon are very busy

This week is a very important time for Buddhists in Cambodia, so the shrines within The Bayon are very busy Now and myself at the Shadow of Angkor guesthouse last night where we had dinner with friends

Now and myself at the Shadow of Angkor guesthouse last night where we had dinner with friends The location of our breakfast spot this morning, next to the Angkor Wat moat, with Sokheng in attendance

The location of our breakfast spot this morning, next to the Angkor Wat moat, with Sokheng in attendanceLabels: Now

Labels: Angkor Wat

Labels: Aki Ra's Boys, Angkor Wat, Banteay Srei, Now, Ta Prohm

Labels: 4Faces, Eric de Vries, Now

Labels: Angkor, Eastern Mebon, Pre Rup, Srah Srang

Labels: Mekong Express, Now, Sokhom

Labels: The Heritage Mission

Labels: Cambodian Premier League

Labels: Khmer Arts Ensemble

At an old school building in Cambodia, the startled face of John Dewhirst stares down from the wall. A teacher from Newcastle, Dewhirst is the only British citizen with his official photograph on display. It's a distinction his sister, Hilary, will curse until the day she dies. Clean-shaven, his long hair neat for the cameras, Dewhirst's portrait is one of thousands pinned around the building. They were taken by the perpetrators of one of the darkest episodes in the history of the human race. Between 1975 and 1979, the school was renamed Tuol Sleng - Hill Of The Poisonous Trees. The sound of children playing and laughing was replaced by screams for mercy as horror stalked the classrooms and corridors.

The communist Khmer Rouge had seized control of Cambodia and transformed the school into a 're- education centre' to hold enemies of 'agrarian socialism' (a return to the Stone Age with peasants working by hand in the fields, and all modern aspects of life outlawed). Pol Pot, the French-educated Khmer Rouge leader, decreed a new Cambodian calendar to start again at Year Zero - a true beginning of the world in which all should live as they did at the dawn of time. Pot, who styled himself Brother Number One, ordered that the entire population should live off the land, with no medicine and starvation rations. Dissidents were eliminated. 'To keep you is no benefit - to destroy you no loss,' was his favoured mantra. After driving the entire Cambodian population out of towns and cities, the Khmer Rouge separated those who could read, write or wore glasses - anyone, in fact, who betrayed signs of being educated. They were taken to Tuol Sleng, where the classrooms were modified in anticipation of their arrival.

Desks and chairs were removed and replaced with iron bed frames, manacles and instruments of torture. In a chilling echo of the Nazi death camps, rooms were set aside for 'medical experiments'. With the borders sealed, inmates were sliced open and had organs removed with no anaesthetic. Some were drowned in tanks of water. Others were attached to intravenous pumps and every drop of blood was drained from their bodies to see how long they could survive. Electric shocks to the genitals were routine. The most difficult prisoners were skinned alive. Babies were held by the feet and swung headfirst against walls, smashing their skulls. Other inmates of Tuol Sleng, also known as S-21, were taken to an infamous place that later became known as the Killing Fields, a beautiful orchard just a few miles away on the outskirts of the capital city, Phnom Penh. There, prisoners were ordered to dig their own graves. Then, to save on bullets, they were bludgeoned to death with iron bars and chunks of wood. Up to 17,000 perished in Tuol Sleng; across Cambodia, almost two million - a quarter of the population - died. Brother Number One brushed aside his blood-lust, saying: 'He who protests is an enemy, he who opposes is a corpse.'

So how did a Briton, on a sailing trip around the Far East with friends, become caught up in this horror? Only now can the full, awful truth about what really happened to John Dewhirst and his companions finally be told. Like much that took place during the years of Cambodia's genocide, there is no happy ending to the story of the Geordie captured by Pol Pot. Indeed, his fate may have been even worse than his friends and family feared at the time. Recently, at the historic trial of the camp commandant, Kaing Guek Eav, disturbing testimony emerged that the 26-year-old and his companions were not executed swiftly, as previously thought. The special UN court in Cambodia heard harrowing claims that the Western sailors were taken outside and burned alive in the streets of the capital, having first endured months of torture and being forced to sign lengthy confessions about their true identities as American spies. Cheam Soeu, 52, a guard at Tuol Sleng, told how he saw fellow Khmer Rouge torturers lead one of the foreign men out on the street at night and force him to sit on the ground. A car tyre was put over him and set alight. 'I saw the charred torso and black burned legs [afterwards],' he said.

Pol Pot had personally given instructions that all evidence of the existence of Dewhirst and his friends was to be destroyed. In a message to his 'fellow brothers' in the Khmer Rouge, their leader stated: 'It's better to kill an innocent by mistake than spare an enemy by mistake.' Kaing Guek Eav, a former teacher, was in charge of Tuol Sleng. Also known as Duch, he is one of five former Khmer Rouge leaders to be tried for crimes against humanity. A cold-blooded killer, Duch used to 'mark' the confessions of his prisoners, sending the papers back to the cells with notes in the margins suggesting improvements to grammar and sentence structure. Every prisoner was forced to pose for photographs soon after capture. The Khmer Rouge leadership was determined to keep an accurate record of all the 'enemies of the revolution' - and even took photos of some of their victims being tortured. They included people caught speaking a foreign language, scavenging for food or crying for dead loved ones. Some Khmer Rouge loyalists were killed for failing to find enough 'counter-revolutionaries' to execute. Duch was a trusted confidant of Pol Pot, and has confirmed that the Westerners were doomed from the moment they were seized and taken to Tuol Sleng. 'I received an order from my superiors that the Westerners had to be smashed and burned to ashes,' he told the court. 'It was an absolute order from my superiors.' This is confirmed by secret Khmer Rouge documents. 'Every prisoner who arrived at S-21 was destined for execution. The policy at S-21 was that no prisoner could be released. Prisoners brought to S-21 by mistake were executed in order to ensure secrecy and security.'

Until the awful events of 1978, John Dewhirst had led an idyllic existence. Born in Newcastle, the family moved to Cumbria when John was 11. A sports enthusiast and climber, he relished outdoor life and spent his boyhood roaming the Cumbrian countryside. He was keen on shooting, fishing and canoeing - yet his older sister, Hilary, says he had a sensitive side, too. As he grew older, John developed a love of literature; he wrote poems and hoped to become a novelist. After finishing his A-levels, and much to the pride of his father, a retired headmaster and his mother, who ran an antiques shop, John won a place to study English at Loughborough University. After finishing his degree and his teacher training, he decided to explore the world - buying a one-way ticket to Tokyo, where he planned to work for a year teaching English, earning enough money to travel back overland to the UK. A popular, laid-back individual, John became good friends with other young westerners in Tokyo. New Zealander Kerry Hamill and Stuart Glass, a Canadian, were part of his circle of friends and the pair owned an old motorised junk called Foxy Lady. Seeking adventure, John quit his teaching post, along with his part-time job on the Japan Times newspaper, and joined Hamill and Glass on a trip sailing round the warm waters of the Gulf of Thailand. They planned to sell Foxy Lady in Singapore and travel on overland. Days were spent fishing and sunbathing, between steering the boat to its next destination. Nights were spent eating fish, drinking beer and looking at the stars. He kept in touch regularly with Hilary, writing her letters once a month. 'He was very happy and very interested in what he was experiencing of a new and different part of the world,' she says.

Then, in early 1978, disaster struck. The Foxy Lady drifted into Cambodian waters. A Khmer Rouge military launch steamed towards them. Stuart Glass, the skipper, was shot dead immediately. Dewhirst and Hamill were seized and taken by military truck to Phnom Penh. At the time, the full scale of the horror inside Cambodia had yet to reach the outside world. Hilary heard that her brother had been captured only after a telephone call from the Foreign Office. A charming and pleasant young man, she still thought John might be able to talk his way to freedom. It was not to be. Duch, the camp commander, was determined to follow his orders to the letter. He instructed his Khmer Rouge underlings to get to work. The torture lasted a month. John Dewhirst and Kerry Hamill endured unimaginable terror. Both wrote lengthy 'confessions'. Under duress, the Englishman admitted that he was a CIA agent on a secret mission to sabotage the Khmer Rouge regime. He claimed that his father had also been a CIA agent, using the cover of 'headmaster of Benton Road Secondary School', and that he had been trained in modern spying techniques at Loughborough. Headed 'Details of my course at the Annexe CIA college in Loughborough, England,' Dewhirst writes that he was taught how to use weapons as part of his induction into the U.S foreign intelligence agency. Mixing elements of his own life story with fiction to satisfy his captors, the Briton also claimed that there were other CIA colleges in the UK - Cardiff, Aberdeen, Portsmouth, Bristol, Leicester and Doncaster. He said his 'handler' was a man called 'Colonel Peter Johnson', and that his university bursar was a CIA major. The confession is signed and dated 5.7.1978. Dewhirst's thumbprint is alongside his signature. Like thousands of other victims in the former school building, which is now a memorial to the dead, the 'confession' was dictated to him by Duch and his interrogators.

John's parents both died before he was captured. At home in Cumbria, 31 years on, Hilary Dewhirst did not attend Duch's trial - at which he initially pleaded guilty. Instead, Rob Hamill, the brother of John's sailing companion Kerry, spoke for both of them, having been handed a note from Hilary to present to the court about her feelings. Facing Duch for the first time, Hamill spoke of wanting to make his brother's killer suffer. 'I've imagined you shackled, starved and clubbed. I have imagined you being nearly drowned and having your throat cut.' But he added: 'It was you who should bear the burden, you to suffer, not the families of the people you killed. From this day forward, I feel nothing towards you. 'To me, what you did removed you from the ranks of being human.' That is a view shared by Hilary. Now a solicitor in Cumbria, she has not uttered John's name in more than three decades. 'I have experienced death and grief. This is different. It's everlasting,' she tells me. 'I can accept death completely. It's what happened to my brother that I can't accept. The fact that the torture was so extreme, lasting not half a day, but months, makes it an inhuman act. It takes the humanity of the person. The person my brother had been, was taken away during that torture. For a human being to do that to another human being - that's not a human act. I don't know how my brother died. I have heard reports of people bleeding to death and having their heads smashed from behind beside mass graves. I don' t know if knowing what really happened can make me feel any worse. If I feel like this after 31 years, a whole country must feel the same.' But she also hopes that some good will come from the trial of her brother's killers. 'What happened in Cambodia isn't generally known to today's generation,' she says. 'It should be part of history lessons. People should remember what happened there.'

The Khmer Rouge was finally driven from power in 1979 after neighbouring Vietnam invaded. What was discovered there shocked the world: the death rate was far higher than during the Nazi holocaust. Pol Pot remained a free man, however, living with the rump of his Khmer Rouge cadres near the border with Thailand until his death in 1998. 'We need to understand the person [Duch] standing there,' adds Hilary. 'He's supposed to be full of remorse. It's an opportunity for him to be held accountable. But, personally, I can't see how it can possibly make any difference.' Yet the trial will help ensure that what happened to John Dawson Dewhirst - proud Englishman, sports fanatic and man of letters - will never be forgotten, along with two million others slaughtered in Cambodia's Killing Fields.

Labels: Duch, John Dewhirst, Kerry Hamill, Khmer Rouge Tribunal

The frontage of these shop houses on Street 108 have undergone only minor changes since their 1931 counstruction

The frontage of these shop houses on Street 108 have undergone only minor changes since their 1931 counstructionLabels: Street 108, The Heritage Mission

Labels: Cambodia U-23s, SEA Games

The photo shows the sampots worn by the dancers - the different colours denote male and female characters

The photo shows the sampots worn by the dancers - the different colours denote male and female charactersLabels: Khmer Arts Ensemble

Labels: Lakhaon Festival

Labels: Khmer Arts Ensemble

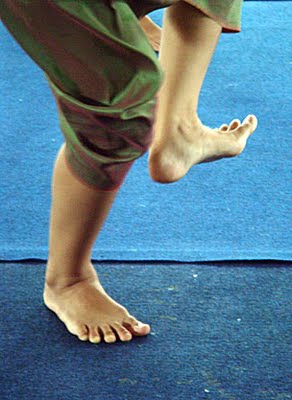

Each dancer must develop great strength in their feet, legs and arms to be able to dance for long periods

Each dancer must develop great strength in their feet, legs and arms to be able to dance for long periods The girls kept expert formation and timing throughout the practice, developed over many months of rehearsals

The girls kept expert formation and timing throughout the practice, developed over many months of rehearsalsLabels: Khmer Arts Ensemble

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Phnom Penh Post

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Nick Sells

Labels: Cambodian Premier League

Labels: Khmer Arts Ensemble

Labels: Olivier Cunin, The Sothea

The Khmer Arts Ensemble will hold an open rehearsal at their Takhmau headquarters tomorrow morning from 9am and will perform their work, Ream Eyso & Moni Mekhala at 7pm on Friday 11 September. Next month, also at Chenla, will be the contemporary dance event, Dansez-Roam, on 16, 17, 24 & 25 October. One face who will not be taking part is Chumvan Sodhachivy, or Belle (pictured) as she's better known to all, who spent the first six months of this year as the associate artist with the French Cultural Center and has just returned from a workshop in Taiwan. In a couple of weeks, she will be off to Europe for two months, working with choreographer Emmanuelle Phuon in Brussels and then completing an internship at the unique National Choreographic Center in Montpellier, France. She simply never stops working.

The Khmer Arts Ensemble will hold an open rehearsal at their Takhmau headquarters tomorrow morning from 9am and will perform their work, Ream Eyso & Moni Mekhala at 7pm on Friday 11 September. Next month, also at Chenla, will be the contemporary dance event, Dansez-Roam, on 16, 17, 24 & 25 October. One face who will not be taking part is Chumvan Sodhachivy, or Belle (pictured) as she's better known to all, who spent the first six months of this year as the associate artist with the French Cultural Center and has just returned from a workshop in Taiwan. In a couple of weeks, she will be off to Europe for two months, working with choreographer Emmanuelle Phuon in Brussels and then completing an internship at the unique National Choreographic Center in Montpellier, France. She simply never stops working.Labels: Belle, Lakhaon Festival

Labels: Greater Mekong, Lonely Planet

This month Waikato man Rob Hamill went to Cambodia to face his brother's killer in a Phnom Pehn courtroom, testifying against Khmer Rouge commander Comrade Duch. Hamilton writer Mark Servian was there as his media support, and reports on Hamill's harrowing journey.

Rob Hamill looked at the judge and said "Limeworks Loop Road, Te Pahu", and on the dusty outskirts of Phnom Pehn my vision stretched and the background seemed to retreat at the mention of that familiar hamlet in the far-away green foothills of Pirongia. Such mundane opening questions – "what is your address?" – to establish his identity. No inquiry to his character, to what he has achieved. For winning a Trans-Atlantic rowing race and breaking world records, or polling highest for the energy trust and fundraising for the hospice, all count for naught in the eyes of this Cambodian court. Here he is just another victim giving testimony, made of the same fragile human flesh that the accused there in the dock rendered and tore asunder so many times. But when asked to identify his family, Rob gives a clue to the man within – he names Kerry and John in the present tense. They ARE his brothers even now, though their deaths three decades ago is what has bought him here, face to face in this room with Comrade Duch (‘Doik’), the Khmer Rouge monster responsible, a mathematician whose victims add up to the tens of thousands.

We had received word that Rob was to testify a day earlier than expected while visiting the scene of those terrible crimes. Rachel his wife, Ivan his two-year-old son and I were visiting Tuol Sleng or S21, the former high school down a Phnom Pehn back street that should be as infamous as Auschwitz. In this place, about the size of Garden Place [or Wgtn’s Civic Square or half of Chch’s The Square], Kerry Hamill landed up in 1978 with fellow lost sailor John Dewhirst. Here they were tortured and abused for months before the final release of death, along with some 15,000 to 20,000 other men, women and children.

Today just inside the gate, Rachel starts crying, sobbing, for she has been living Kerry’s story for years and now she stands in the place that has loomed so large in her and Rob’s imagination. The guide asks where we’re from and we say "New Zealand", he says "I took a New Zealander whose brother was here around the other day", Rachel says, "he’s my husband". Rob visited Tuol Sleng a few days earlier and found it very hard to take. He says he arrived in Cambodia wanting to find some way in his heart to forgive Duch. But experiencing this torture factory first hand banished any chance of that. In Rob’s words, Duch "no longer belongs to the human species". For this man, who as a young student won national mathematics prizes, designed the deliberate considered processes of this torture factory. Duch alone gave the order to "smash" each and every one of his victims.

As we see and have these horrors described, Rachel’s sobbing stops. As she says later, and is as true for me, "you just feel numb after a while". We see tiny brick cells with bloodstains on the floor, balconies barb-wired to prevent escape by suicide, makeshift but efficient torture devices and tools, hundreds of photos of faces both before and after death. And actually worse of all, the paintings by Vann Nath, one of only seven survivors, that document what he witnessed. Rob later asserts that the inmates were treated like animals, but really, if animals are ever treated like this, it is called what it is - cruelty.Initially ‘Angkar’, or the ‘Khmer Rouge’ as we in the West know them, only targeted the ‘new people’- the city dwellers, wearers of glasses, the intellectuals, but also factory workers and mechanics, anyone involved in the modern economy (the ‘old people’ were the rural subsistence-living ‘peasants’). But as Pol Pot’s paranoia increased, Angkar turned on their own and started torturing and killing their own ranks. The foreigners that Duch got his hands on served to prove that the enemies were at the gate, tortured into falsely confessing they were CIA or KGB agents. Kerry Hamill was killed just two or so months before the Vietnamese overthrew Pol Pot in January 1979. Before Rob’s arrival, Duch’s trial at the Extraordinary Court Chambers of Cambodia has already established that Kerry and other foreigners were burnt with tyres around their necks in order to destroy the evidence.

The debate in court has been over whether or not they were alive when this was done. A few weeks back, an ex-guard had testified that they were, but Duch maintains that he ordered that they be killed first and that no one would have disobeyed him. This is typical of how Duch has tried to run the courtroom from the dock, in a different manner but with the same intellectual arrogance that we saw from Clayton Weatherston back in New Zealand a few weeks ago. Duch converted to Christianity in the mid-90s and, unlike the other senior Khmer Rouge yet to be tried, has pleaded guilty to all charges – the court case is to decide his sentence and to cross-examine him in the French inquisitorial style. But having been arrested in 1999, he has had ten years to prepare his defence. So while he has often said sorry and asked forgiveness, his aloof behaviour in court does not match his words and he splits such horrible hairs – death by tyre or machete? – to qualify what he did. ‘I was only following orders, they would have done it to me’ is his defence. But Duch was a senior leader in the regime and, as Rob has often said, it was those in positions of power who could have stopped the madness.

Rob arrived in Cambodia the week before to prepare his testimony with Alain Werner, the Swiss lawyer representing some of the ‘civil parties’. They have redrafted it numerous times, and on this Monday Rob farewelled us to go and complete it for his scheduled appearance the next day. But mid-morning I get the call that he is likely to be on that afternoon, interrupting my, Rachel and Ivan’s numbing tour of Tuol Sleng. By the time we arrive at the crowded courthouse, thunder rumbling in the tropical sky, Rob is already in the courtroom and we are told that Ivan, being under sixteen, is not allowed in. So we take up position in the media room next door and watch proceedings via closed-circuit TV. Rob’s appearance starts with the mundane identity questions, and then he embarks on the sad tale of his brother and family. As he begins, at Rachel’s request, I call Rob’s sister who is looking after Ivan’s older brothers back in Te Pahu, handing her the phone when she answers – "Rob is on now," she says, signalling this moment none of them ever thought they would see.

The first picture he puts up on the screen is of the Hamill brothers in a dinghy when they were kids. In this sticky warm corner of South-East Asia, the dated image of young Kiwis is jarring, prompting the Western reporters in the room to jump up and snap shots of it. As Rob then tells what happened to two of the boys on that boat, Rachel quietly cries, Ivan asleep on her lap. After half-an-hour of this gruelling testimony, the court takes a break, and suddenly Alain rushes into the room, as if he has jumped out of the screen, his lawyerly robe flapping, a bundle of energy suddenly exploding in the quiet room. He’s been sent by Rob to find Rachel, concerned that she isn’t in the courtroom with him. We explain that Ivan isn’t allowed in – "sort it out" I snap, sending Alain flying back out the door, only to return moments later to report they won’t budge. Rachel reluctantly hands me Ivan, waking the two-year-old. As she disappears the toddler objects, throwing his legs around, but eventually calming down.

When Rob resumes he starts by acknowledging his wife to the court and thanks her for her support. When he then puts up a picture of Kerry on the screen, Ivan calls out ‘Daddy!’, mistaking the uncle he’ll never know for his father. Rob continues to tell how the actions of Duch and co affected his family. As Ivan occasionally calls for his mum, it strikes me that his upset at her absence is yet one more tiny ripple of Duch’s cruelty all those years ago. Around us, the international and local media watch riveted, Rob clearly making the most intense appearance in the months-long trial. When he says to Duch "there have been times when, to use your word, I have wanted to smash you", the Cambodians in the room, some listening to translation on headphones, gasp and laugh to each other, shaking their heads in disbelief. This reaction continues as he describes how in the past he has imagined Duch suffering the tortures he has visited on so many others. It is stirring and disturbing stuff, delivered by a man who is renowned for his bravery, strength and endurance, but who today shows an emotional vulnerability that is painful to watch. Towards the end of his appearance, Rob gets the chance to ask Duch where his brother’s ashes are. Duch stands stiffly, and calmly claims that he simply doesn’t remember Kerry, though he does recall his British companion John Dewhirst .

And then it is over, and Rachel reappears to reclaim Ivan and we are all shown into a side room to see Rob. There is happiness of a sort, interspersed with a sombre realisation that while the family has finally had a chance to speak their minds to Duch, many questions still remain. Ivan jumps around on the couch behind his parents, happy to have his dad back. Rob looks numb, speaking softly, smiling occasionally, a feeling of unreality pervading the room. Alain the lawyer appears and expresses his huge thanks and, his arms swinging around in an almost comically typical Gallic fashion, declares that Rob has just made the most decisive testimony of the trial.

With the crowds of the day gone, Rob steps out into the cool shadow of the building to talk to the media. He is composed, the emotion of the testimony subsided, his usual confident soap-box self to the fore again, the same as when I saw him speak at the opening of the Farmers Market at Claudelands a fortnight earlier. The media session over, Sambath Reach, the court official who has ushered us around, steps forward to speak to the small clutch of Westerners. He expresses his deep thanks to Rob "on behalf of all Cambodians" for saying things that have not previously been said in the court and for standing up to Duch in a way no one has yet dared. Like every local over forty we meet, he lost several family members to the Khmer Rouge. As he speaks, we know we are standing at a point in history.

Sambath then invites Rob over to the court’s Buddhist shrine nearby. In the warm angled tropical sun, the tall late afternoon storm clouds stacked in the distance, the Kiwi and the Khmer stand before the canopied golden warrior statue and make an offering for Kerry and all the other poor souls who fell into the hands of that dreadful beast. The pair quietly discuss the shrine’s story, the calm of the moment a blessed relief. Rob bows to the statue and thanks Sambath, squeezing his hand and meeting his eye one last time. And then he puts an arm around Rachel, picks up Ivan, and together the family walk off. Perhaps, just perhaps, the lost soul of a sailor from Whakatane, a beloved brother, can now finally rest in peace.

Labels: Brother Number One, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Rob Hamill

Labels: Elegy, John McDermott

Labels: Cambodian Premier League, Phnom Penh Post

Labels: Cambodian Premier League

Labels: Cambodian Premier League

Labels: Belle, We're Gonna Go Dancing

La Relais de Chhlong hotel in all its glory

La Relais de Chhlong hotel in all its gloryLabels: Chhlong, Mekong Discovery Trail, Relais de Chhlong

Labels: Lightning