He clicked, they died

Tuol Sleng, or S-21, to give its official title, remains the predominant focus of the Khmer Rouge trials taking place at the ECCC just outside Phnom Penh. The witnesses, in the case against the former S-21 chief Duch, this week have been in the main, civil parties rather than oath-swearing tribunal witnesses, and their testimony has been less than watertight under questioning by the court's judges and lawyers. We haven't seen the chief photographer at S-21, Nhem En, take the stand yet but I'm sure it must happen sooner or later. You may recall that a short film, 'The Conscience of Nhem En', was up for an Oscar recently and was shown for the first time on HBO in the States last night. He is not a person to whom you immediatley warm. If ever. His interviews have displayed a coldness for his actions as a member of the Khmer Rouge and a penchant for self-publicity and financial gain doesn't sit well with most people. In my archives, I found this article about Nhem En, by Philip Jacobson for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine in February 1998, which is worth repeating here.

The photographer of death - by Philip Jacobson (Sunday Telegraph Magazine)

Soon after the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia's civil war in 1975, the Pol Pot regime plucked one of its fanatical young guerrillas from the ranks and sent him to China to learn how to take photographs. Six months later, Nhem En, then aged 16, returned to Phnom Penh where he reported to prison compound S-21 in an outlying suburb of the capital. On his first day there, En learned what the job of chief photographer at the Tuol Sleng compound would entail: photographing those marked down for death. Like the Nazis before them, the leaders of the revolution that plunged Cambodia back into 'Year Zero' were obsessed with preserving a record of the hideous crimes committed in its name. Two decades later, not long after a pair of American journalists came across a vast cache of his negatives, En himself stumbled out of the jungle to surrender. Philip Jacobson reports on the photographer who documented genocide.

Over the course of 30 months, Nhem En produced some 10,000 full-face 'mugshots' for attachment to the dossiers of the columns of men, women and children that wound through his makeshift studio. Under orders never to respond to their anxious questions, he would snap them against a white-washed wall with an identification number pinned to their chests before guards hustled them away. En had no illusions about the fate that awaited his subjects: the S-21 prison compound was already known to those living nearby as a place 'where people go in but never come out'. Virtually everyone held there could expect to be tortured savagely to extract confessions or phantasmagoric crimes against the revolution: in their agony, illiterate peasants would admit to being spymasters for foreign powers. After that, prisoners were taken to a killing field 10 miles away and clubbed to death or suffocated with plastic bags, bullets being too valuable for traitors. By the time an invading Vietnamese army overthrew Pol Pot in January 1979, more than 14,000 people had been 'processed' through S-21, leaving just seven survivors to testify to the horror. The Vietnamese did not find En but they found 6,000 of his abandoned negatives. The grainy prints these negatives yielded were exhibited in what became the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, where Cambodians would occasionally recognise a face staring out at them.

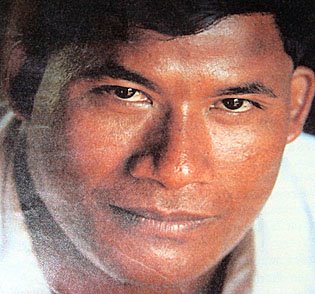

In the early Nineties, two young American photojournalists working in Cambodia, Doug Niven and Chris Riley, stumbled across the same cache of 6cm by 6cm negatives that had been left to decay in rusty filing cabinets. Brushing away dust and mildew, they were transfixed by the images they saw. 'We looked at each other and said, "Hey, this is amazing, we have to do something with this stuff," ' Riley recalls. On their own initiative, they launched an ambitious project to raise funds to clean and catalogue this unique material and produce high-quality pints from it. The level quality of the work suggested a trained eye behind the camera. 'Some survivors vaguely remembered a guy who took pictures - quite a decent man, it seems, who would slip prisoners water when the guards weren't looking,' says Riley. But when work began on the archive, the identity of the photographer in the charnel house was still a mystery. It was not until 1995 that a stocky, dark-skinned Khmer Rouge fighter clutching a battered camera and a kalashnikov rifle emerged from the jungle in northern Cambodia to surrender to government forces. It turned out that when the Vietnamese had invaded, Nhem En had fled with other prison staff to join resistance units in the remote countryside and had remained there for almost 20 years. Now 39, he had finally wearied of war and hardship. His reappearance would open a fresh chapter in the terrible history of S-21.

Last November, an enterprising Associated Press reporter in Phnom Penh persuaded En to talk on the record about his experiences at Tuol Sleng, hesitantly at first, then in grim but compulsive detail. "Those who arrived at the faculty had no chance of living,' he told Robin McDowell, recalling the sea of faces 'filled with fear and deep sadness' that had passed before his camera. En said he often shot hundreds of photographs every day, whilst his five apprentices toiled in a primitive darkroom to turn out the stream of prints. 'I knew I was taking pictures of innocent people,' En acknowledged, 'but I knew also that if I said anything, I would be killed. The Tuol Sleng killing machine operated around the clock, En added, recalling 'constant cries and screams' as shifts of torturers worked on their victims. When officials who had been purged from the Khmer Rouge government arrived, Pol Pot required copies of En's photographs of them - both before and after execution - as proof that they had been disposed of. En himself survived a brush with 'Comrade Number 1' after he was ordered to process film taken during the Cambodian leader's visit to China in 1977. When one print came out with spots on Pol Pot's eyes, En was detained and accused of insulting the revolution: somehow he convinced his interrogators that faulty film was to blame, conceivably saving himself from being returned to S-21 for liquidation. One day, En recognised through the lens his own cousin, Chhan - accused of being a CIA agent - 'but I kept silent, even after he was taken away'. In October last year, En returned to Tuol Sleng for the first time, to see if Chhan's picture was there. He said he could not find it and left the museum 'feeling very, very sad'.

The knowledge of what happened at S-21 makes a visit to the complex of scruffy three-storey buildings set around the old school playground a wrenching experience. A profound sense of evil pervades the musty cell blocks: in a former interrogation room, a bedframe to which prisoners were strapped during torture remains in place, the floor around it deeply stained. The impact of En's stark black-and-white pictures is even more devastating, burning the faces of the mute and anonymous dead into the mind's eye. Flaws in the negatives have etched black spots like bullet holes into some of the portraits or splashed them with what looks like blood. Many of those photographed by En seem already to have retreated into themselves, resigned and expressionless: a black-clad woman stares into the camera as if it were the barrel of a gun, while the tiny, ghostly hand of a child grips her sleeve. A youth stands with hands tied behind his back, seemingly untroubled by the safety-pin that fastens the number 17 into the flesh of his bare chest. Two men are manacled together in one of En's shots: only at second glance do you see they have locked hands in a desperate embrace. Yet others among En's subjects appear calm and relaxed, like the boy draped in a gaily patterned scarf who smiles as if the picture was intended for a mother or sweetheart. A teenage girl in a clinging crocheted blouse looks almost coquettish, a handsome, silver-haired man shoots a look of pure contempt at the lens.

Professor David Chandler, the distinquished historian of Cambodia, says that in viewing these images that were never intended to be seen we enter a world where everybody is condemned to death. In his introduction to a book of En's pictures, The Killing Fields, Chandler concludes that this 'may also bring us face to face... with what the psychiatrist Carl Jung called our shadow selves. We are inside S-21 [where] we become interrogators, prisoners and passers-by'. Niven and Riley say they always intended the Tuol Sleng archives to serve as a monument to victims of the genocide and 'give them a louder voice today'. All the money the pictures earn is ploughed back into the project. Albums of contact sheets displaying every cleaned-up portrait were provided to the museum. While a BBC team was making a television documentary there two years ago, a woman identified her missing husband in one of them. It is perfectly legitimate to be repulsed by the pictures, Riley observes. "I still find it hard to look at them myself.' He also understands critics of the travelling exhibition of a selection of 100 prints who question whether what one called 'souls on the point of departure' can be described as art. 'But Doug and I believe these faces represent something radically different from written accounts of the killing fields, speaking a kind of visual language, if you like. We don't want people who see them to feel like voyeurs but like witnesses to the catastrophe that overwhelmed Cambodia.'

The coda to the story of the Tuol Sleng pictures comes from Doug Niven, who has had several long conversations with En after contacting him in January last year (Niven speaks serviceable Khmer). En told him that he joined the Khmer Rouge at the age of 10: as the son of a dirt-poor bean farmer whose wife died young, he had impeccable proletarian credentials for a revolutionary movement founded on a visceral hatred of the bourgeoise. "En said he began as a supply porter, but was soon absorbed into a combat unit and saw a lot of hard fighting before the Khmer Rouge victory,' Niven recalls. He was not at all comfortable with questions about his zealous and obedient service in S-21, Niven adds. 'As far as I'm aware, En has never shown any remorse for what he was doing at Tuol Sleng, which I find pretty disturbing. On the other hand, I'm certain he understands that his role in the genocide is quite likely to come up for examination one day, and that makes him very wary.' After fleeing Tuol Sleng in 1979, En had become a soldier once more, but he was subsequently assigned to take photographs (using two cameras found on a battlefield) for the crudely printed 'newsletters' circulated in zones still under Khmer Rouge control. En told Niven that by then he had lost all faith in the revolution and wanted to live under democracy, but he could not explain convincingly why he continued to serve Pol Pot for so long.

'En strikes me as a born survivor, a lot smarter and more focused than any of the other defectors I've met,' says Niven. "There's a kind of inner toughness about guys who've been hard-core Khmer Rouge for as long as him.' On a trip to En's village, where his wife was about to give birth, Niven discoveref that he had abandoned a different wife and six children when he decided to change sides - 'that didn't seem to bother him too much.' When En saw the beautifully produced book of his photographs from Tuol Sleng, says Niven, 'you could see him figuring out if there was going to be anything in this for him'. His new life was hard, he told Niven, describing how the present Cambodian government had trained him to recruit other defectors in a distant province where he lived in an old wooden house with a tin roof and a battery-powered television set. En said he was keen to move back into photography and since then he has tried his hand, with little success, covering the fighting that still plagues Cambodia. His latest idea, Nevin reports, is to go into the wedding picture business.

Labels: Conscience of Nhem En, Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, S-21