Thursday, November 26, 2009

Monday, September 21, 2009

Testimony complete

A new book on the Tribunal will be launched by DC-Cam at Monument Books on Saturday 3 October (6pm). It's called On Trial: The Khmer Rouge Accountability Process and is a collection of essays by seven authors on what the trial represents. The authors, John D Ciorciari and Anne Heindel, are both legal advisors with DC-Cam and the 352-page book has a foreword by Youk Chhang, its director. John Ciorciarai has already published a 200-page book, The Khmer Rouge Tribunal, back in 2006. And we are still awaiting the release of Bou Meng's A Survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison S-21, written by Vannak Huy, which has been put on hold during the trial of Comrade Duch. Also in the works is a monograph history of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum by Yin Nean, which should be out sometime next year.

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, On Trial

Friday, September 11, 2009

An Englishman at S-21

The Englishman butchered in Cambodia's killing fields: The terrifying tale of the British tourist who blundered into horror of Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge - by Andrew Malone, The Daily Mail (UK)

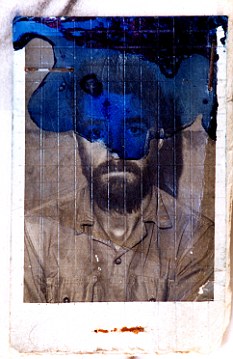

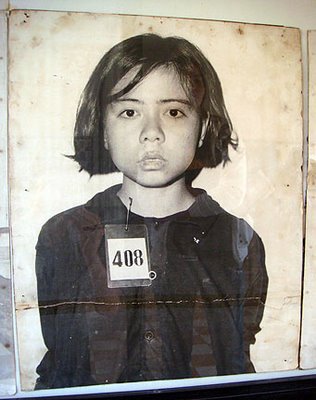

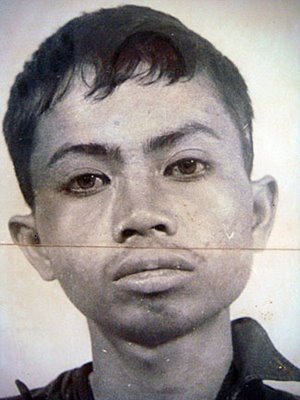

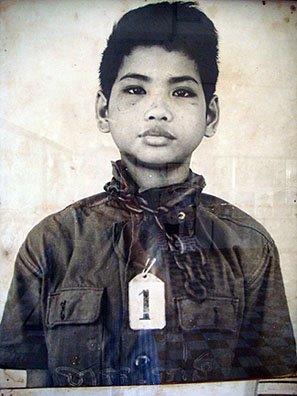

At an old school building in Cambodia, the startled face of John Dewhirst stares down from the wall. A teacher from Newcastle, Dewhirst is the only British citizen with his official photograph on display. It's a distinction his sister, Hilary, will curse until the day she dies. Clean-shaven, his long hair neat for the cameras, Dewhirst's portrait is one of thousands pinned around the building. They were taken by the perpetrators of one of the darkest episodes in the history of the human race. Between 1975 and 1979, the school was renamed Tuol Sleng - Hill Of The Poisonous Trees. The sound of children playing and laughing was replaced by screams for mercy as horror stalked the classrooms and corridors.

The communist Khmer Rouge had seized control of Cambodia and transformed the school into a 're- education centre' to hold enemies of 'agrarian socialism' (a return to the Stone Age with peasants working by hand in the fields, and all modern aspects of life outlawed). Pol Pot, the French-educated Khmer Rouge leader, decreed a new Cambodian calendar to start again at Year Zero - a true beginning of the world in which all should live as they did at the dawn of time. Pot, who styled himself Brother Number One, ordered that the entire population should live off the land, with no medicine and starvation rations. Dissidents were eliminated. 'To keep you is no benefit - to destroy you no loss,' was his favoured mantra. After driving the entire Cambodian population out of towns and cities, the Khmer Rouge separated those who could read, write or wore glasses - anyone, in fact, who betrayed signs of being educated. They were taken to Tuol Sleng, where the classrooms were modified in anticipation of their arrival.

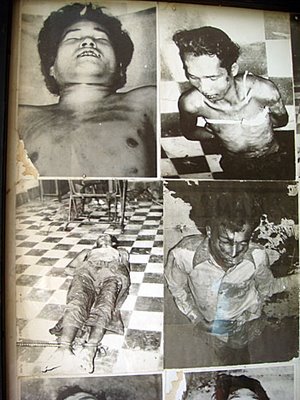

Desks and chairs were removed and replaced with iron bed frames, manacles and instruments of torture. In a chilling echo of the Nazi death camps, rooms were set aside for 'medical experiments'. With the borders sealed, inmates were sliced open and had organs removed with no anaesthetic. Some were drowned in tanks of water. Others were attached to intravenous pumps and every drop of blood was drained from their bodies to see how long they could survive. Electric shocks to the genitals were routine. The most difficult prisoners were skinned alive. Babies were held by the feet and swung headfirst against walls, smashing their skulls. Other inmates of Tuol Sleng, also known as S-21, were taken to an infamous place that later became known as the Killing Fields, a beautiful orchard just a few miles away on the outskirts of the capital city, Phnom Penh. There, prisoners were ordered to dig their own graves. Then, to save on bullets, they were bludgeoned to death with iron bars and chunks of wood. Up to 17,000 perished in Tuol Sleng; across Cambodia, almost two million - a quarter of the population - died. Brother Number One brushed aside his blood-lust, saying: 'He who protests is an enemy, he who opposes is a corpse.'

So how did a Briton, on a sailing trip around the Far East with friends, become caught up in this horror? Only now can the full, awful truth about what really happened to John Dewhirst and his companions finally be told. Like much that took place during the years of Cambodia's genocide, there is no happy ending to the story of the Geordie captured by Pol Pot. Indeed, his fate may have been even worse than his friends and family feared at the time. Recently, at the historic trial of the camp commandant, Kaing Guek Eav, disturbing testimony emerged that the 26-year-old and his companions were not executed swiftly, as previously thought. The special UN court in Cambodia heard harrowing claims that the Western sailors were taken outside and burned alive in the streets of the capital, having first endured months of torture and being forced to sign lengthy confessions about their true identities as American spies. Cheam Soeu, 52, a guard at Tuol Sleng, told how he saw fellow Khmer Rouge torturers lead one of the foreign men out on the street at night and force him to sit on the ground. A car tyre was put over him and set alight. 'I saw the charred torso and black burned legs [afterwards],' he said.

Pol Pot had personally given instructions that all evidence of the existence of Dewhirst and his friends was to be destroyed. In a message to his 'fellow brothers' in the Khmer Rouge, their leader stated: 'It's better to kill an innocent by mistake than spare an enemy by mistake.' Kaing Guek Eav, a former teacher, was in charge of Tuol Sleng. Also known as Duch, he is one of five former Khmer Rouge leaders to be tried for crimes against humanity. A cold-blooded killer, Duch used to 'mark' the confessions of his prisoners, sending the papers back to the cells with notes in the margins suggesting improvements to grammar and sentence structure. Every prisoner was forced to pose for photographs soon after capture. The Khmer Rouge leadership was determined to keep an accurate record of all the 'enemies of the revolution' - and even took photos of some of their victims being tortured. They included people caught speaking a foreign language, scavenging for food or crying for dead loved ones. Some Khmer Rouge loyalists were killed for failing to find enough 'counter-revolutionaries' to execute. Duch was a trusted confidant of Pol Pot, and has confirmed that the Westerners were doomed from the moment they were seized and taken to Tuol Sleng. 'I received an order from my superiors that the Westerners had to be smashed and burned to ashes,' he told the court. 'It was an absolute order from my superiors.' This is confirmed by secret Khmer Rouge documents. 'Every prisoner who arrived at S-21 was destined for execution. The policy at S-21 was that no prisoner could be released. Prisoners brought to S-21 by mistake were executed in order to ensure secrecy and security.'

Until the awful events of 1978, John Dewhirst had led an idyllic existence. Born in Newcastle, the family moved to Cumbria when John was 11. A sports enthusiast and climber, he relished outdoor life and spent his boyhood roaming the Cumbrian countryside. He was keen on shooting, fishing and canoeing - yet his older sister, Hilary, says he had a sensitive side, too. As he grew older, John developed a love of literature; he wrote poems and hoped to become a novelist. After finishing his A-levels, and much to the pride of his father, a retired headmaster and his mother, who ran an antiques shop, John won a place to study English at Loughborough University. After finishing his degree and his teacher training, he decided to explore the world - buying a one-way ticket to Tokyo, where he planned to work for a year teaching English, earning enough money to travel back overland to the UK. A popular, laid-back individual, John became good friends with other young westerners in Tokyo. New Zealander Kerry Hamill and Stuart Glass, a Canadian, were part of his circle of friends and the pair owned an old motorised junk called Foxy Lady. Seeking adventure, John quit his teaching post, along with his part-time job on the Japan Times newspaper, and joined Hamill and Glass on a trip sailing round the warm waters of the Gulf of Thailand. They planned to sell Foxy Lady in Singapore and travel on overland. Days were spent fishing and sunbathing, between steering the boat to its next destination. Nights were spent eating fish, drinking beer and looking at the stars. He kept in touch regularly with Hilary, writing her letters once a month. 'He was very happy and very interested in what he was experiencing of a new and different part of the world,' she says.

Then, in early 1978, disaster struck. The Foxy Lady drifted into Cambodian waters. A Khmer Rouge military launch steamed towards them. Stuart Glass, the skipper, was shot dead immediately. Dewhirst and Hamill were seized and taken by military truck to Phnom Penh. At the time, the full scale of the horror inside Cambodia had yet to reach the outside world. Hilary heard that her brother had been captured only after a telephone call from the Foreign Office. A charming and pleasant young man, she still thought John might be able to talk his way to freedom. It was not to be. Duch, the camp commander, was determined to follow his orders to the letter. He instructed his Khmer Rouge underlings to get to work. The torture lasted a month. John Dewhirst and Kerry Hamill endured unimaginable terror. Both wrote lengthy 'confessions'. Under duress, the Englishman admitted that he was a CIA agent on a secret mission to sabotage the Khmer Rouge regime. He claimed that his father had also been a CIA agent, using the cover of 'headmaster of Benton Road Secondary School', and that he had been trained in modern spying techniques at Loughborough. Headed 'Details of my course at the Annexe CIA college in Loughborough, England,' Dewhirst writes that he was taught how to use weapons as part of his induction into the U.S foreign intelligence agency. Mixing elements of his own life story with fiction to satisfy his captors, the Briton also claimed that there were other CIA colleges in the UK - Cardiff, Aberdeen, Portsmouth, Bristol, Leicester and Doncaster. He said his 'handler' was a man called 'Colonel Peter Johnson', and that his university bursar was a CIA major. The confession is signed and dated 5.7.1978. Dewhirst's thumbprint is alongside his signature. Like thousands of other victims in the former school building, which is now a memorial to the dead, the 'confession' was dictated to him by Duch and his interrogators.

John's parents both died before he was captured. At home in Cumbria, 31 years on, Hilary Dewhirst did not attend Duch's trial - at which he initially pleaded guilty. Instead, Rob Hamill, the brother of John's sailing companion Kerry, spoke for both of them, having been handed a note from Hilary to present to the court about her feelings. Facing Duch for the first time, Hamill spoke of wanting to make his brother's killer suffer. 'I've imagined you shackled, starved and clubbed. I have imagined you being nearly drowned and having your throat cut.' But he added: 'It was you who should bear the burden, you to suffer, not the families of the people you killed. From this day forward, I feel nothing towards you. 'To me, what you did removed you from the ranks of being human.' That is a view shared by Hilary. Now a solicitor in Cumbria, she has not uttered John's name in more than three decades. 'I have experienced death and grief. This is different. It's everlasting,' she tells me. 'I can accept death completely. It's what happened to my brother that I can't accept. The fact that the torture was so extreme, lasting not half a day, but months, makes it an inhuman act. It takes the humanity of the person. The person my brother had been, was taken away during that torture. For a human being to do that to another human being - that's not a human act. I don't know how my brother died. I have heard reports of people bleeding to death and having their heads smashed from behind beside mass graves. I don' t know if knowing what really happened can make me feel any worse. If I feel like this after 31 years, a whole country must feel the same.' But she also hopes that some good will come from the trial of her brother's killers. 'What happened in Cambodia isn't generally known to today's generation,' she says. 'It should be part of history lessons. People should remember what happened there.'

The Khmer Rouge was finally driven from power in 1979 after neighbouring Vietnam invaded. What was discovered there shocked the world: the death rate was far higher than during the Nazi holocaust. Pol Pot remained a free man, however, living with the rump of his Khmer Rouge cadres near the border with Thailand until his death in 1998. 'We need to understand the person [Duch] standing there,' adds Hilary. 'He's supposed to be full of remorse. It's an opportunity for him to be held accountable. But, personally, I can't see how it can possibly make any difference.' Yet the trial will help ensure that what happened to John Dawson Dewhirst - proud Englishman, sports fanatic and man of letters - will never be forgotten, along with two million others slaughtered in Cambodia's Killing Fields.

Labels: Duch, John Dewhirst, Kerry Hamill, Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Emotions run high

Rob Hamill fought to control his emotions during the testimony according to news reports as he described in detail how the death of his brother had affected his family and what Hamill himself wanted to do in retribution against Duch. Kerry Hamill and his fellow adventurers had been captured by the KR navy when their boat Foxy Lady strayed into territorial waters on 13 August 1978. Stuart Glass was killed immediately, while Kerry Hamill and Brit John Dewhirst (pictured) were taken to S-21. The last confession of Kerry Hamill is dated 13 October 1978, less than three months before the KR regime crumbled in the face of the Vietnamese invasion. Yesterday, Rob Hamill told Duch; "at times I have wanted to smash you, to use your words, in the same way that you smashed so many others. At times I have imagined you shackled, starved, whipped and clubbed viciously. I have imagined your scrotum electrified, being forced to eat your own faeces, being nearly drowned and having your throat cut. I have wanted that to be your experience, your reality." His 13-page statement lasted just under an hour and he was allowed to direct six questions to Duch, though the answers he got back were non-specific and 'nondescript'. A documentary film, Brother Number One, is being made that follows Rob's journey to Cambodia to find out the truth about what happened to his elder brother. To read Rob Hamill's statement, click here.

Rob Hamill fought to control his emotions during the testimony according to news reports as he described in detail how the death of his brother had affected his family and what Hamill himself wanted to do in retribution against Duch. Kerry Hamill and his fellow adventurers had been captured by the KR navy when their boat Foxy Lady strayed into territorial waters on 13 August 1978. Stuart Glass was killed immediately, while Kerry Hamill and Brit John Dewhirst (pictured) were taken to S-21. The last confession of Kerry Hamill is dated 13 October 1978, less than three months before the KR regime crumbled in the face of the Vietnamese invasion. Yesterday, Rob Hamill told Duch; "at times I have wanted to smash you, to use your words, in the same way that you smashed so many others. At times I have imagined you shackled, starved, whipped and clubbed viciously. I have imagined your scrotum electrified, being forced to eat your own faeces, being nearly drowned and having your throat cut. I have wanted that to be your experience, your reality." His 13-page statement lasted just under an hour and he was allowed to direct six questions to Duch, though the answers he got back were non-specific and 'nondescript'. A documentary film, Brother Number One, is being made that follows Rob's journey to Cambodia to find out the truth about what happened to his elder brother. To read Rob Hamill's statement, click here.Labels: Brother Number One, Duch, John Dewhirst, Kerry Hamill, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Rob Hamill

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Contrition, my arse

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Voices from the ECCC

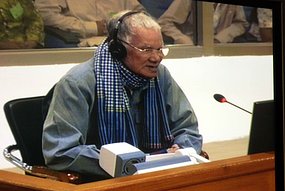

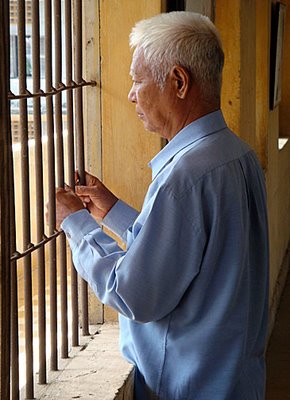

It took 45 minutes on the back of a moto to reach the ECCC entrance some 16kms outside of Phnom Penh along Route 4. I arrived at the same time as coaches ferrying villagers from Siem Reap drew up in the car park. Security was very tight, hence no photos from the day, and taking my place in the public gallery, the court began at 9am on the dot. Soon after every seat in the gallery was occupied. My first view of the defendant Duch, through the glass divide, was of him leafing through Voices from S-21, small in stature, looking every inch the studious schoolteacher, flanked by two security guards. He looked confident and at home in the courtroom and his playful interactions with his lawyers at the breaks rubber-stamped that. David Chandler (DC) was called in and sat with his back to the gallery but with his face superimposed on four large tv screens, as well as a pc on the desk directly in front of him. He provided a few brief details about himself and then his research, which began in the early 1990s, then full-time on the book from 1994 until he handed it to the publishers in 1998. He'd studied microfilm archives, the S-21 archives and also at DC-Cam as well as interviewing Vann Nath twice, a couple of S-21 guards including Him Huy and the photographer Nhem En. I had to suppress a wry smile that DC had come over from Australia to testify, whilst Nhem En, who lives in Anlong Veng, couldn't attend the trial this week and had his testimony read out instead.

David Chandler giving testimony today. Photo courtesy of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia

David Chandler giving testimony today. Photo courtesy of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of CambodiaIn response to questions from the defense, DC said he was "extremely moved and impressed by Duch's admission of guilt" after Francois Roux reminded everyone that Duch has already pleaded guilty, though it was pretty clear to me that if they can pin the majority of the blame elsewhere they will. Son Sen looks the best candidate, especially as he's dead. Roux kept referring to the French edition of Voices, which DC bitterly complained about, calling his work 'the meat in a Francophile sandwich,' after the publisher made changes about which he was very unhappy. Duch then had an opportunity to address the court and spent 10 minutes offering his sincere respect and appreciation to DC for his observations regarding his work and DC's search for the truth, and his gratitude for writing about S-21, which he called "1 flower in a garden of 100 flowers in the DK government." There was no direct conversation between Duch and DC. The court adjourned at 4.15pm and I managed a quick hello to DC before making my way out and back home. An enthralling day, to see the court in action at last (and yes, it's incredibly slow, but what do you expect when everything has to be translated into Khmer, English and French), to see DC in the same room as Duch, to watch Duch at such close quarters entirely comfortable with his lot - which just seems so wrong - and to witness so many Khmer citizens coming to see for themselves that justice is finally being sought.

Labels: David Chandler, Duch, ECCC, Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

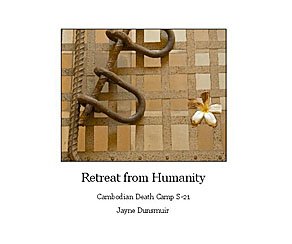

Retreat from Humanity

This is timely as I hope to get along to the ECCC on Thursday to hear expert testimony in the Khmer Rouge trial of former S-21 chief Duch from leading historian David Chandler. I mentioned a couple of weeks ago about the plethora of self-published books available from blurb.com about Cambodia. One such book is Jayne Dunsmuir's Retreat from Humanity: Cambodian Death Camp S-21. It's a 64-page photo essay book showing some of her S-21 pictures alongwith accompanying text on the nature of torture, excerpts from interviews with former prisoners and guards and information on the trial of KR leaders. Jayne published it at the beginning of 2008 and is keen to get it sold at Tuol Sleng with profits going to the museum. She's sending me a copy of her book to see if that's possible. Jayne also won an honourable mention in the International Photography Awards in 2008 with a series of 5 portraits of Cambodian people - 2 of which are printed at the end of the book. Find out more about the book here.

This is timely as I hope to get along to the ECCC on Thursday to hear expert testimony in the Khmer Rouge trial of former S-21 chief Duch from leading historian David Chandler. I mentioned a couple of weeks ago about the plethora of self-published books available from blurb.com about Cambodia. One such book is Jayne Dunsmuir's Retreat from Humanity: Cambodian Death Camp S-21. It's a 64-page photo essay book showing some of her S-21 pictures alongwith accompanying text on the nature of torture, excerpts from interviews with former prisoners and guards and information on the trial of KR leaders. Jayne published it at the beginning of 2008 and is keen to get it sold at Tuol Sleng with profits going to the museum. She's sending me a copy of her book to see if that's possible. Jayne also won an honourable mention in the International Photography Awards in 2008 with a series of 5 portraits of Cambodian people - 2 of which are printed at the end of the book. Find out more about the book here.Labels: David Chandler, Duch, Jayne Dunsmuir, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Retreat from Humanity, S-21

Monday, July 27, 2009

More than 30 years on

The date, 12 August, has been set for Rob Hamill's appearance as a civil party in the trial of Comrade Duch at the ECCC. New Zealander Hamill (pictured) is better known as an Olympic and Trans-Atlantic champion rower, but he's also the brother of Kerry Hamill, captured, tortured and murdered under Duch's supervision of S-21 in 1978. Nearly 31 years to the day of his brother's capture off the coast of Cambodia, Rob Hamill says of his opportunity to face Duch in court; “I expect to experience the widest possible range of emotions when I see Duch, a lot of nervous energy will be expended. Duch says he is sorry and wants forgiveness, but I want to find out whether he truly understands the impact of what he did and the damage he caused. I’m not sure that he does comprehend what he and the Khmer Rouge did to the people of Cambodia, let alone to the families of Kerry, John and Stuart.” His brother Kerry Hamill and Briton John Dewhirst were snatched from their storm-blown yacht, and fellow sailor Canadian Stuart Glass was killed, on 13 August 1978. Kerry and John were tortured for two months at S-21 and forced to falsely confess they were CIA spies, before they were killed and their bodies most likely burnt and buried at Tuol Sleng. A film, Brother Number One, is being made that follows Rob's journey to Cambodia to find out the truth of what happened to his elder brother. Read more here.

The date, 12 August, has been set for Rob Hamill's appearance as a civil party in the trial of Comrade Duch at the ECCC. New Zealander Hamill (pictured) is better known as an Olympic and Trans-Atlantic champion rower, but he's also the brother of Kerry Hamill, captured, tortured and murdered under Duch's supervision of S-21 in 1978. Nearly 31 years to the day of his brother's capture off the coast of Cambodia, Rob Hamill says of his opportunity to face Duch in court; “I expect to experience the widest possible range of emotions when I see Duch, a lot of nervous energy will be expended. Duch says he is sorry and wants forgiveness, but I want to find out whether he truly understands the impact of what he did and the damage he caused. I’m not sure that he does comprehend what he and the Khmer Rouge did to the people of Cambodia, let alone to the families of Kerry, John and Stuart.” His brother Kerry Hamill and Briton John Dewhirst were snatched from their storm-blown yacht, and fellow sailor Canadian Stuart Glass was killed, on 13 August 1978. Kerry and John were tortured for two months at S-21 and forced to falsely confess they were CIA spies, before they were killed and their bodies most likely burnt and buried at Tuol Sleng. A film, Brother Number One, is being made that follows Rob's journey to Cambodia to find out the truth of what happened to his elder brother. Read more here.Labels: Brother Number One, Duch, John Dewhirst, Kerry Hamill, Rob Hamill, S-21

Monday, July 20, 2009

Perpetrators squawk

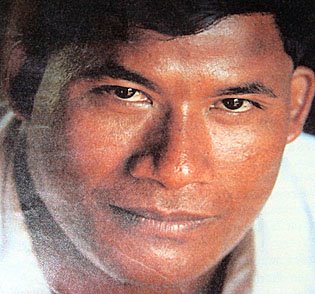

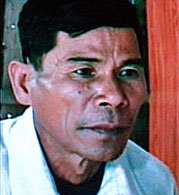

The testimony from Khmer Rouge cadre like Him Huy, who last week admitted to transporting thousands of prisoners from Tuol Sleng to their deaths at Choeung Ek, will continue this week. Him (pictured) will be back in the witness box today, as he relates more details in the case against the S-21 chief Comrade Duch, who is clearly still able to exert a degree of influence over some of the witnesses. Him has already confessed to killing one individual in his testimony last week, though other testimony to DC-Cam investigators in the past, suggests Him was responsible for a lot more deaths. However, minimising their role in the Khmer Rouge slaughter has been a factor for all of the former KR who've appeared at the ECCC to-date. Even Duch, who has admitted responsibility for his actions, has been choosing his words carefully and claiming he ordered his subordinates to carry out instructions from above, but didn't actually get involved in the nitty gritty of what went on in the interrogation rooms at S-21. Who is he trying to kid? I don't have a list of future witnesses though I would expect people like Nhem En, who was the chief photographer of prisoners as they arrived at S-21, and interrogator Prak Khan to be called to testify. Nhem En is hardly ever out of the news, whether he's trying to sell Pol Pot's sandals, his own cameras or begging for money for his Anlong Veng museum. Prak Khan has a much lower profile though documents from S-21 clearly show his involvement in the torture that took place and he also showed up in Rithy Panh's film about S-21, when he confessed he thought of the prisoners as 'animals.' After the dismal failure of Mam Nay as a witness last week, let's hope that this week we'll hear more accurate testimony about the inner workings of S-21 and the activities of Comrade Duch. There's paper talk today about another request being sent by investigators at the tribunal to the King Father, Norodom Sihanouk. I can't imagine that he will agree to appear at the trials, though he has begun to serialize his memoirs of his imprisonment by the KR on his official website (in French).

The testimony from Khmer Rouge cadre like Him Huy, who last week admitted to transporting thousands of prisoners from Tuol Sleng to their deaths at Choeung Ek, will continue this week. Him (pictured) will be back in the witness box today, as he relates more details in the case against the S-21 chief Comrade Duch, who is clearly still able to exert a degree of influence over some of the witnesses. Him has already confessed to killing one individual in his testimony last week, though other testimony to DC-Cam investigators in the past, suggests Him was responsible for a lot more deaths. However, minimising their role in the Khmer Rouge slaughter has been a factor for all of the former KR who've appeared at the ECCC to-date. Even Duch, who has admitted responsibility for his actions, has been choosing his words carefully and claiming he ordered his subordinates to carry out instructions from above, but didn't actually get involved in the nitty gritty of what went on in the interrogation rooms at S-21. Who is he trying to kid? I don't have a list of future witnesses though I would expect people like Nhem En, who was the chief photographer of prisoners as they arrived at S-21, and interrogator Prak Khan to be called to testify. Nhem En is hardly ever out of the news, whether he's trying to sell Pol Pot's sandals, his own cameras or begging for money for his Anlong Veng museum. Prak Khan has a much lower profile though documents from S-21 clearly show his involvement in the torture that took place and he also showed up in Rithy Panh's film about S-21, when he confessed he thought of the prisoners as 'animals.' After the dismal failure of Mam Nay as a witness last week, let's hope that this week we'll hear more accurate testimony about the inner workings of S-21 and the activities of Comrade Duch. There's paper talk today about another request being sent by investigators at the tribunal to the King Father, Norodom Sihanouk. I can't imagine that he will agree to appear at the trials, though he has begun to serialize his memoirs of his imprisonment by the KR on his official website (in French).Labels: Duch, Him Huy, Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

Who is the real Mam Nay?

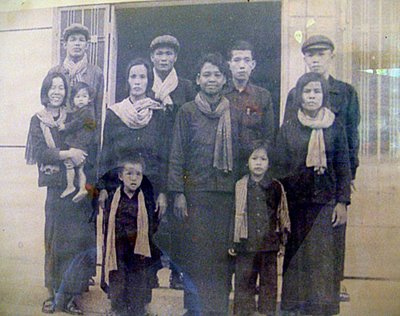

This picture hangs at S-21. On the far left is the tall upright figure of Comrade Chan (Mam Nay). The man without a cap is Comrade Duch, the S-21 chief, with his wife, Chhim Sophal (alias Rom) in front of him. The picture was taken by S-21's chief photographer Nhem En in 1976.

This picture hangs at S-21. On the far left is the tall upright figure of Comrade Chan (Mam Nay). The man without a cap is Comrade Duch, the S-21 chief, with his wife, Chhim Sophal (alias Rom) in front of him. The picture was taken by S-21's chief photographer Nhem En in 1976.Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Mam Nay, S-21

Hiding to nothing

The chief interrogator, Mam Nay, a man with more blood on his hands, literally, than Comrade Duch, his former boss at S-21, made a very brief appearance in the witness box at the Khmer Rouge tribunal yesterday. Whilst defense lawyers pointed out that the witness might well incriminate himself whilst giving evidence, the prosecutor gave an assurance that Mam Nay (pictured, CNN) would not be prosecuted in the ECCC. However, that didn't negate a possible prosecution in a Cambodian court at a later date, so the judges adjourned prematurely so the witness could seek legal advice. Why this wasn't done beforehand is beyond me but is another example of delays and time wastage at the ECCC. The evidence collected by DC-Cam over the last decade suggests that Mam Nay will be a key witness in the case against the former S-21 chief Duch, but if he corroborates that evidence, then Mam Nay will be admitting to interrogation, torture and the death in custody of S-21 inmates. It's part of the bigger question that has been debated for decades, if you prosecute only the leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime then the underlings who followed orders and carried out the killings go free. In the case of Mam Nay, the documentary evidence found at S-21 details his role in the torture and killings, moreso than many killers in other locations. Essentially, he's on a hiding to nothing if he tells the truth. Mam Nay, now 76, was known by the alias Chan during his time as Duch's number 2 at S-21. He carried out interrogations of the senior cadre incarcerated at Tuol Sleng such as former KR minister Hu Nim, and according to Duch, also interrogated Western prisoners. Like Duch he had been a teacher in Kompong Thom province and imprisoned by the Sihanouk regime before he re-joined the KR in the early '70s and linked up again with Duch at S-21. In the late 1990s, after the defection of the Pailin-based KR to the government in 1996, Mam Nay became a policeman in Battambang province, though when Duch was arrested in 1999 he went underground, resurfacing in Pailin a few years later.

The chief interrogator, Mam Nay, a man with more blood on his hands, literally, than Comrade Duch, his former boss at S-21, made a very brief appearance in the witness box at the Khmer Rouge tribunal yesterday. Whilst defense lawyers pointed out that the witness might well incriminate himself whilst giving evidence, the prosecutor gave an assurance that Mam Nay (pictured, CNN) would not be prosecuted in the ECCC. However, that didn't negate a possible prosecution in a Cambodian court at a later date, so the judges adjourned prematurely so the witness could seek legal advice. Why this wasn't done beforehand is beyond me but is another example of delays and time wastage at the ECCC. The evidence collected by DC-Cam over the last decade suggests that Mam Nay will be a key witness in the case against the former S-21 chief Duch, but if he corroborates that evidence, then Mam Nay will be admitting to interrogation, torture and the death in custody of S-21 inmates. It's part of the bigger question that has been debated for decades, if you prosecute only the leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime then the underlings who followed orders and carried out the killings go free. In the case of Mam Nay, the documentary evidence found at S-21 details his role in the torture and killings, moreso than many killers in other locations. Essentially, he's on a hiding to nothing if he tells the truth. Mam Nay, now 76, was known by the alias Chan during his time as Duch's number 2 at S-21. He carried out interrogations of the senior cadre incarcerated at Tuol Sleng such as former KR minister Hu Nim, and according to Duch, also interrogated Western prisoners. Like Duch he had been a teacher in Kompong Thom province and imprisoned by the Sihanouk regime before he re-joined the KR in the early '70s and linked up again with Duch at S-21. In the late 1990s, after the defection of the Pailin-based KR to the government in 1996, Mam Nay became a policeman in Battambang province, though when Duch was arrested in 1999 he went underground, resurfacing in Pailin a few years later.One witness who did complete her evidence yesterday was Nam Mon, an alleged survivor of two secret detention facilities run by Duch. She testified that she saw Duch beat two of her uncles to death, the first evidence presented to the trial that Duch killed someone with his own hands. As to be expected, Duch dismissed the evidence that Nam Mon had worked as a medic at S-21 as 'far from reality.'

Update: In his evidence today, Mam Nay claimed he never tortured anyone, and was just responsible for 'asking questions of lowly cadre and Vietnamese prisoners.' He's obviously decided to downplay his role at S-21 completely to save his own skin and is unlikely to say anything that will incriminate himself, and therefore much of what he says can be taken with a large pinch of salt. He's not on trial so I'm not sure whether prosecutors' will be allowed to submit evidence that disputes his version of events. He's the first of the S-21 perpetrator witnesses to give evidence though I wouldn't exactly call him a creditable and reliable witness, though some will say who can blame him as he seeks to avoid future prosecution or even revenge attacks.

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Mam Nay, S-21

Thursday, July 9, 2009

He clicked, they died

Labels: Conscience of Nhem En, Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, S-21

Friday, May 15, 2009

Dunlop on Duch

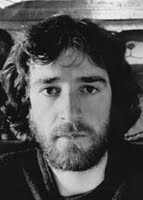

The freelance journalist who tracked down and exposed Comrade Duch, then wrote about his investigations in the excellent book, The Lost Executioner, and who I first heard about for his work on the 1994 book War of the Mines, Nic Dunlop (pictured), will be holding court at Meta House on Tuesday 19th May at 7pm. Dubbed a 'grown-up Harry Potter' by one fellow journo, Dunlop's expose on the man who oversaw thousands of interrogations and executions at Tuol Sleng is a fine book, well worth reading and will no doubt be covered as part of the Q&A that will take place at Meta House after a short documentary screening on the night. Bangkok-based, his current work is a photo-led project on Burma's dictatorship, though with the Duch trial taking place in Phnom Penh right now, you can appreciate he is more interested than most.

The freelance journalist who tracked down and exposed Comrade Duch, then wrote about his investigations in the excellent book, The Lost Executioner, and who I first heard about for his work on the 1994 book War of the Mines, Nic Dunlop (pictured), will be holding court at Meta House on Tuesday 19th May at 7pm. Dubbed a 'grown-up Harry Potter' by one fellow journo, Dunlop's expose on the man who oversaw thousands of interrogations and executions at Tuol Sleng is a fine book, well worth reading and will no doubt be covered as part of the Q&A that will take place at Meta House after a short documentary screening on the night. Bangkok-based, his current work is a photo-led project on Burma's dictatorship, though with the Duch trial taking place in Phnom Penh right now, you can appreciate he is more interested than most.Link: website.

To refresh memories, here's my review of The Lost Executioner: A Story of the Khmer Rouge:

Nic Dunlop's first-rate detective story on the trail of Pol Pot's chief executioner, the notorious Comrade Duch, is a fascinating journey into Cambodia's recent bloody history. Through a series of testimonies by Duch's family members and people who knew him, Dunlop builds up a compelling picture of this former teacher turned mass murderer, whilst also giving us a running commentary on the development of the Khmer Rouge organisation through the eyes of former cadre such as Sokheang, now a human rights investigator though formerly a Khmer Rouge sympathiser. The Lost Executioner is Dunlop's first book; he's primarily a photographer who became obsessed with S-21, known to many as Tuol Sleng, and its commandant, Comrade Duch. He even kept a photo of Duch in his pocket. By an astonishing stroke of luck, Dunlop met the man responsible for the deaths of more than 20,000 people, in Samlaut, a small town in northwest Cambodia in 1999 and exposed him with the help of Nate Thayer and the Far Eastern Economic Review, leading to his arrest and detention, awaiting trial. Dunlop's subsequent investigations and interviews now provide us with a great wealth of detail about Duch's life before, during and after the Khmer Rouge reign of terror though ultimately the reason for Duch's transformation into a brutal killer remains an unexplained puzzle. In a perverse twist, Duch converted to Christianity, had worked for an American charity, was living under a new identity and had returned to teaching before his unmasking. The book is written in an easy to follow though powerful narrative and I recommend The Lost Executioner to anyone seeking to delve into the morass that is Cambodia's recent past. It's a remarkable and revealing story. [pic Chor Sokunthea]

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Nic Dunlop

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

The day of reckoning beckons

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Tuol Sleng

Saturday, February 14, 2009

Trials underway

Masters of Cambodia's killing fields face justice at last - by Anne Barrowclough

Him Huy, a seasoned executioner at Tuol Sleng, studied the list of names of people he would kill that night. When the silent, terrified prisoners had been lifted on to his lorry he drove them out to the pretty orchard on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. There, he took them one by one to the ditches that had been freshly dug, forced them to kneel and clubbed them to death with an iron bar. “Sometimes it took just one blow, sometimes two,” he told The Times. “After I clubbed them someone else would slit their throats. But every time I clubbed someone to death I would think, tomorrow, this might be me kneeling here, with one of the other guards killing me.”

In the orgy of cruelty unleashed on Cambodia during the insane years of Pol Pot's rule, Tuol Sleng, formerly a high school, was to become a symbol of the apocalyptic state the Khmer Rouge created. Enveloped in secrecy and identified only by the code name S-21, it existed solely to interrogate and kill the men and women incarcerated behind its walls, the vast majority of whom would never leave it alive. From 1976, until Vietnamese troops took over Phnom Penh in January 1979, as many as 17,000 men, women and children were taken to S-21 to be interrogated for counter-revolutionary crimes, and then killed. Only 14 are known to have survived, although recent evidence suggests that five child prisoners may have escaped and still be alive today. Thousands of innocents died here - but so too did members of Pol Pot's own circle, Khmer Rouge soldiers and the prison's own guards. “Out of my interrogation unit of 12, only I survived,” said Prak Khan, a soldier who became a torturer at the prison. The man who presided over the atrocities of Tuol Sleng with fanatical devotion was Kang Kek Ieu, also known as Comrade Duch, who was posted to S-21 in 1976. He goes to trial this week, accused of crimes against humanity.

Today Cambodia is, on the surface, a peaceful country with a thriving tourist industry. Casual conversations with Cambodians reveal nothing of the horrors of the Khmer Rouge years. But behind the superficial serenity, the people are still traumatised by their memories. In interviews with The Times, the prison survivors, guards and even those who carried out the worst atrocities described Duch as a man of almost sub-human cruelty, who instilled terror into prisoners and guards. Bou Meng, an artist who was taken to S-21 in 1977, remembers how Duch would visit the room where he and dozens of other prisoners were shackled to the floor. “He ordered me to beat the man beside me with a bamboo cane while he watched,” he said. “Then Duch ordered the man to beat me. You could see the pleasure in his face.” Duch was a frequent visitor to the torture rooms, where he drove the interrogation units to ever-harsher techniques as they worked through the day and night in four-hour shifts. “The sound of screaming was all around us all the time,” said Vann Nath, a former prisoner and now a renowned artist.

Duch brought the orderly mind of a dedicated teacher to S-21. He kept a meticulous record of the prison's workings and read every confession. Often, he would send them back with corrections marked in red pen, as if they were the test papers of a reluctant student. “Sometimes the confessions came back saying, ‘must get more from the prisoner',” said Prak Khan. The prisoners were deemed guilty simply because they had been accused - and it was the interrogators' duty to force them to admit that guilt. Many admitted to crimes they did not even understand. “I had not even heard of the CIA,” said Bou Meng. “But they beat me with bamboo rods and electric cables until I confessed that I worked for the CIA and the KGB.”

“We kept torturing them until they confessed,” said Prak Khan. “If they didn't, the torture got worse. We pulled out their finger and toenails and gave them electric shocks. Sometimes we would tie a bag over their head so they suffocated. We'd take it off just as they were about to fall unconscious. If they still didn't confess, they'd be killed.” Some inmates were sent to a clinic to “donate” blood to the army hospitals. Prak Khan, whose interrogation room was adjacent to the doctors' clinic, said: “They would bring the prisoners blindfolded and tie them to the beds with their legs and arms spread out. They attached lines to their arms. The tubes led to a bottle on the floor. They pumped all the blood out until the bodies were limp. Then they threw the bodies into pits outside.”

The routine was always the same for the prisoners taken to S-21. Told they were being taken from their homes to work as teachers, doctors or mechanics, they were handcuffed on arrival, photographed and forced into cells, often 60 at a time, where they were shackled by the ankle. They were banned from speaking to guards or each other. At night they were not allowed even to turn over without permission. “If the guards heard our shackles they would beat us,” said Chum Mey, a mechanic. He spent his first two weeks being tortured day and night. “They pulled out my fingernails and toenails. Then they put electric wires in my ears. I heard the generator and then I felt the fire coming out of my eyes. After 12 days and 12 nights I signed their confession and they took me to a big room with other prisoners. Every night we waited to hear the trucks come. If midnight arrived and they hadn't come we knew we would live another 24 hours.”

The guards lived through their own hell. Him Huy, known to the prisoners as “Cruel Him”, said: “One day I would be guarding prisoners with another soldier and that afternoon the other soldier would be arrested. You always expected to be arrested.” Prak Khan often recognised old friends among the people taken into S-21. “When I heard the names of people I knew, I pretended I didn't know them,” he said. “If I showed I recognised them I would be killed too.” After the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia in 1979, Duch disappeared into the jungle. In 1996 he met a group of American missionaries and converted to Christianity. A journalist discovered him working as a medical orderly in 1999 and he was arrested, at last, by the Cambodian police. On Tuesday Bou Meng, Chum Mey and the S-21 guards will be among the scores of Cambodians who will crowd into a courtroom to see their tormentor brought to trial. Duch has since apologised to the survivors of S-21 but it is not enough. “He asked my forgiveness,” said Bou Meng. “I could not give it to him.”

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal