Not on trial

Labels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Ta Mok

Cambodia - Temples, Books, Films and ruminations...

Labels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Ta Mok

A pal of mine, Eric de Vries will open his new gallery-cafe in Siem Reap very soon - 24 April to be precise - and the following story appeared in the Phnom Penh Post during my absence last week. In addition, Eric has launched the 4Faces website at www.4faces.net.

A pal of mine, Eric de Vries will open his new gallery-cafe in Siem Reap very soon - 24 April to be precise - and the following story appeared in the Phnom Penh Post during my absence last week. In addition, Eric has launched the 4Faces website at www.4faces.net.Labels: 4Faces, Eric de Vries

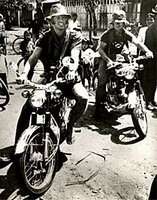

One story that never seems to be far from the public eye is the disappearance of two photojournalists, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, who were last seen in 1970 as they rode their motorbikes into Khmer Rouge-held territory. Vietnam war photographer Tim Page has been in Cambodia recently continuing his search for the truth about what happened to them and I'm told is positive he's found Sean Flynn's last resting place. There's a book and a documentary in the offing I believe. Another book about the pair, Two of the Missing, Remembering Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, has just been updated and republished in paperback by Press 53. This new edition contains 18 pages of photographs by and of these two photojournalists. Most of these photos have never been published before. "Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were among the bravest and best of that daring young crew of photographers who covered the Vietnam War," says author and friend Perry Deane Young. "Flynn was on assignment for Time magazine and Stone was a cameraman with CBS when they were last seen heading around a Communist roadblock near the Cambodian town of Chi Pou." Director Ralph Hemecker has optioned the film rights to the book and is now in the process of casting. The screenplay was written by Young and Hemecker. Young is the author of three plays and nine books, including the bestseller, the David Kopay Story. A journalist with UPI during the Vietnam War, he remembers his close friends and colleagues as he examines their lives and wonders what led them to take this one final risk. Young also includes profiles of several other colleagues who took very different paths from Flynn and Stone, including the legendary madcap English photographer Tim Page.

One story that never seems to be far from the public eye is the disappearance of two photojournalists, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, who were last seen in 1970 as they rode their motorbikes into Khmer Rouge-held territory. Vietnam war photographer Tim Page has been in Cambodia recently continuing his search for the truth about what happened to them and I'm told is positive he's found Sean Flynn's last resting place. There's a book and a documentary in the offing I believe. Another book about the pair, Two of the Missing, Remembering Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, has just been updated and republished in paperback by Press 53. This new edition contains 18 pages of photographs by and of these two photojournalists. Most of these photos have never been published before. "Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were among the bravest and best of that daring young crew of photographers who covered the Vietnam War," says author and friend Perry Deane Young. "Flynn was on assignment for Time magazine and Stone was a cameraman with CBS when they were last seen heading around a Communist roadblock near the Cambodian town of Chi Pou." Director Ralph Hemecker has optioned the film rights to the book and is now in the process of casting. The screenplay was written by Young and Hemecker. Young is the author of three plays and nine books, including the bestseller, the David Kopay Story. A journalist with UPI during the Vietnam War, he remembers his close friends and colleagues as he examines their lives and wonders what led them to take this one final risk. Young also includes profiles of several other colleagues who took very different paths from Flynn and Stone, including the legendary madcap English photographer Tim Page.Labels: Sean Flynn, Tim Page

Smiling kids in a remote village on the 'ride from hell' between Stung Treng and Preah Vihear province

Smiling kids in a remote village on the 'ride from hell' between Stung Treng and Preah Vihear province One of Tim's dolphin shots at Kratie, his photos were much better than mine, as the dolphins played hide and seek with both of us

One of Tim's dolphin shots at Kratie, his photos were much better than mine, as the dolphins played hide and seek with both of usLabels: Kratie dolphins, Preah Vihear

Nice to see that Goal.com have picked up the story I broke two weeks ago here that the Cambodian national football team coach Prak Sovannara has rung the changes after the team's three-match losing sequence at the Suzuki Cup finals in December by introducing 9 new faces into his squad, as they prepare for the AFC Challenge Cup group matches in Bangladesh at the end of next month. Here's the article, obviously re-worded from my own, that appeared in the South East Asia section of their website. It's good that someone at least took the trouble to give Cambodia a plug at all. Talking of the national team, their left-sided midfielder-cum-winger Chan Rithy played for the Phnom Penh Crown team as they collected the Hun Sen Cup on Saturday amid speculation that he could be off to play in the Thai Premier League next season. It's something I mooted a while ago that maybe 3 or 4 of the national team's best players need to take flight and go and play in some of the higher standard football around Asia to improve their skill, technique and big-game experience in order to bring that to bear in the international arena. I'm talking about keeper Samreth Seiha, Chan Rithy, Sun Sovannarith and the striking duo of Khim Borey and Kouch Sokumpheak. Anyway, here's that Goal.com article.

Nice to see that Goal.com have picked up the story I broke two weeks ago here that the Cambodian national football team coach Prak Sovannara has rung the changes after the team's three-match losing sequence at the Suzuki Cup finals in December by introducing 9 new faces into his squad, as they prepare for the AFC Challenge Cup group matches in Bangladesh at the end of next month. Here's the article, obviously re-worded from my own, that appeared in the South East Asia section of their website. It's good that someone at least took the trouble to give Cambodia a plug at all. Talking of the national team, their left-sided midfielder-cum-winger Chan Rithy played for the Phnom Penh Crown team as they collected the Hun Sen Cup on Saturday amid speculation that he could be off to play in the Thai Premier League next season. It's something I mooted a while ago that maybe 3 or 4 of the national team's best players need to take flight and go and play in some of the higher standard football around Asia to improve their skill, technique and big-game experience in order to bring that to bear in the international arena. I'm talking about keeper Samreth Seiha, Chan Rithy, Sun Sovannarith and the striking duo of Khim Borey and Kouch Sokumpheak. Anyway, here's that Goal.com article.Labels: Cambodia football

For the last few years, the U.N. has been sponsoring a weary, bickering, increasingly fruitless war crimes tribunal to condemn the last five senior members of the Pol Pot regime. In the summer of 2008, I watched in disbelief as Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister, was judged "unfit" to stand trial for mental health reasons. This year, it has been the turn of the sinister Duch, the commandant of Tuol Sleng. The others on trial are Khieu Samphan, the former nominal head of state; Noun Chea, Pol Pot's deputy, and Ieng Thirith. But this month in Phnom Pehn I noticed that the papers were also filled with rumors that the UN was threatening to pull out of a trial seen as being manipulated by the nervous Prime Minister Hun Sen. The slippery Hun Sen is an ex-Khmer Rouge himself, after all, and he has many skeletons in his capacious cupboards.

On the streets, meanwhile, the most ubiquitous genocide book by far is a slender volume with the modest title, A Cambodian Prison Portrait: A Year in the Khmer Rouge's S-21. Unwrap the plastic and you enter the most harrowing memoir of them all, a first-person account of the Khmer Rouge years by a naive country painter named Vann Nath: one of only seven men to survive Tuol Sleng. Sixteen thousand others were not so lucky. Some have called Vann Nath the Goya of the genocide, which was contrived by the Maoist regime of Democratic Kampuchea between 1975 and 1979. It was a period in which the strange, secretive dictator Pol Pot - whose real name was Saloth Sar - tried to create what the British historian Philip Short has called "the first modern slave state." Upon emerging victorious from a long guerrilla war against the U.S.-backed government of Lon Nol, Pol Pot's militant Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and drove millions of people into the countryside to work in collective farms. Twenty thousand died on the road in the first few days of the regime and during the next three years and 10 months, 200,000 were executed as "traitors." In total, between 1.5 million and 2 million died. When the Vietnamese army finally drove Pol Pot back into the jungles of western Cambodia, the country was strewn with the remains of the so-called killing fields.

But the Khmer Rouge did not cease to terrorize Cambodia. Supported by China, Thailand and the U.S., Pol Pot himself fought on in the wild Cardamom Mountains near the town of Pailin, on the border with Thailand. Atrocities continued. In 1994, Khmer Rouge units attacked a train on the Phnom Pehn-Kampot line and executed dozens of people, including three westerners. In 1997, the former Khmer Rouge propaganda minister Son Sen was murdered with his wife and children on Pol Pot's direct orders--a lurid crime that led to the dictator's downfall inside his own movement. Only with Pol Pot's death in 1998 did the movement begin to peter out, and the almost supernatural fear he inspired begin to recede.

Vann Nath's electrifying, primitivist images inspired by Bollywood movie posters and drawn directly from memory, are the only testimony to what happened inside S-21, a former French school in the heart of the city where thousands were tortured and murdered under the eye of the psychopathic Duch. It's a paradox of torture (and genocide, for that matter) that it can rarely if ever actually be photographed as it happens. But it can be painted. Like Duch, Vann Nath is quite a well-known character in Phnom Pehn. He owns a large Khmer restaurant on Czechoslovakia Street with a dark dining room walled with bamboo and filled with the kind of miniature red-lit Chinese shrines that look like shrunken porn stores. He wasn't difficult to find in the end. A slightly stooped, white-haired man with a kindly, beaten-up face, he is to be found in his restaurant almost every day, self-effacingly holding court with a trickle of visitors and playing with his grandchildren.

You see at once the wounded, hunted eyes and the slight sense of bemusement--it's a face older than its years and yet somehow also younger. When you are one of only seven people who emerge alive from a killing machine that exterminated thousands, you inevitably wonder why it was you and not someone else. As Vann Nah explains in his book, he was only spared because he was a reasonably competent artist. Duch plucked him from the execution lists because he thought he might be able to produce a few decent propaganda portraits of Brother Number One, as Pol Pot was known. (The execution orders still survive, with Duch's signature at the bottom of a long list of Vann Nath's fellow prisoners and a red line under Vann Nath's name with a comment to one side suggesting that he be spared.)

We sat in the gloom of the dining room in the middle of the afternoon, under plastic vine leaves on trellises, while he ordered me a Khmer feast: mo-cou kroeung, a fiery sour soup, and spiced omelettes called pong teair. Vann Nath has his painting studio upstairs above the restaurant and, for all his odd celebrity, it's a quiet life now, by his own admission--daily painting, family and the business. Like most Khmers, he is reticent, refined, never raising his voice or making emphatic gestures. But from time to time he covers his face with a hand in a gesture of apparent nervousness. He said that he had never dreamed his life would turn out this way, that his work would become the most instantly recognizable icon of a surreal state crime. "I thought I would be painting landscapes. Indeed, I have now gone back to painting landscapes." On Jan. 7, 1978, the 33-year-old painter was arrested. As usual with the Khmer Rouge, there was no explanation, no credible charge; the whole process was somewhat mysterious.

Equally inexplicably, Vann Nah was tortured by electrocution. The questions were always the same. Was he a member of the CIA? The Vietnamese sympathizers? The KGB? He had never heard of any of them. He was then bundled into a convoy bound for Phnom Pehn, still with no idea what he had been arrested for. Instantly, he was catapulted into a Dostoyevskian world of secrecy, paranoia and terror. None of his fellow prisoners knew what they had been arrested for either. It hardly mattered. Decades later, many Khmer Rouge cadres freely admitted that most of the people they had murdered were innocent. Killing innocents was as important as killing the guilty. "Better to kill a thousand innocent people than let a single guilty one go," was one of the Khmer Rouge's cryptically absurd slogans. In the converted classrooms of S-21, prisoners were shackled together with iron bars. They were not permitted to talk, urinate, stand or even turn their bodies without asking permission from the ferocious teenage guards. If they ate cockroaches to supplement the appalling food, they were beaten savagely - sometimes to death. The guards knew, even if the prisoners didn't, that everyone there was doomed to die anyway.

Vann Nath's gripping paintings show many of these scenes: prisoners being flogged, water-boarded, their nails ripped out, their throats cut (it was rumored that blood was collected in this way and peddled to Phnom Pehn hospitals). In a 2003 documentary made by Rithy Panh, Vann Nath re-visited Tuol Sleng with some of the former guards, who were outwardly unrepentant. With demented enthusiasm, they re-enacted their cruelties - revolutionary children tormenting their elders. They stormed up and down the corridors for the cameras, screaming at the ghosts of long-dead prisoners. Vann Nath and Chum Mey, another survivor, watched them in stupefaction. "Pol Pot was always obsessed with the Cambodians disappearing as a race," Van Nath said in the restaurant. "There was this racial hysteria about the Vietnamese, about the Khmers being conquered and assimilated. But during that whole time I kept wondering if the Khmers were simply destroying themselves. I wondered, how can we do this to ourselves? Is it self-hatred? Are we trying to wipe ourselves from the face of the earth?"

We went upstairs to the open-air studio on the first floor - a terrace overlooking the tin rooftops. It was the rainy season and the skies lit up with monstrous flashes of lightning. The studio paintings were a mix: half political paintings, half idyllic, sunset-drenched landscapes filled with Ankgorian ruins, water buffalo and the timeless villages that seem to reside in the Khmer unconscious as a kitsch memory of a lost Eden. They are the kinds of images you see everywhere at Angkor Wat, sold by scores of artists by the roadside. But the Tuol Sleng images are something else. Also derived from memory, they have the gritty, driving force of a personal pathology. Among them stood one of the hallucinatory pictures of Pol Pot, clearly inspired by the iconography of Mao. Looking at it, I was reminded of a curious observation by the French writer Pierre Loti upon visiting the ruin of Banon at Angkor Wat, which is famous for its giant smiling faces of King Jayavarman VII. Loti found the temple terrifying because of those faces, which showed the smile of totalitarian power and cruelty, of calm implacability. When I told Vann Nath this he seemed to recognize the parallel. "Yes, I can see that. I made Pol Pot smile like that because that's what they wanted."

Like a miniature gulag, Tuol Sleng had its hierarchies, its survival strategies (futile in the end, of course) and its resident sadists. Over it all presided the cool, methodical, pedantic Duch, who took pride in the exactness of his bookkeeping. Every day he came into the studio, where a handful of artists were being kept alive for official purposes, and examined their progress. The executioners always came with him. I wondered how Vann Nah felt about Duch now. "Duch was always polite to me. He would come in and look at my portraits and admit that I was making a good effort. We both knew that if I didn't make that effort I would be taken out and shot with the others, but he could pretend to joke about it. He asked me to make Pol Pot look young and fresh. I ended up making him look like a teenage girl, with the pink cheeks. Duch was delighted. I was allowed to live."

Duch was himself a curious character. A former math teacher who had come under the sway of Maoism in the '60s, he was the same age as Vann Nath and had fought in the jungle army of Pol Pot for years. As it happens, he also interrogated the French scholar Francois Bizot in 1971 after Bizot was captured by the Khmer Rouge near Angkor Wat. The portrait of Duch in Bizot's book, The Gate, was unforgettable enough. Mildly sadistic and a fanatical Communist, Duch had spared Bizot because the latter could play chess and speak Khmer. This odd Frenchman was intriguing and Duch was too curious about him to have him shot. To Bizot, there was a cat and mouse quality to their relationship, and perhaps the same had been true for Vann Nath. Vann Nath's images are more than paintings, and they cannot be judged merely aesthetically. They are folk stories lit by a sudden flash of pornographic horror. His images of water-boarding, a technique used daily at Tuol Sleng, have recently found their way all over the Internet in the light of recent controversies, though few know the story behind them. For many in the West, it was their first actual image of the technique. It shows how the archaic tool of painting has once again become strangely powerful and relevant in the age of digital media.

The faded black and white photographs from 1975, "Year Zero" of the regime, often look like something from the distant past, like views of the Middle Ages. Our sense of distance from them is already extraordinary. But Vann Nath's brilliantly colored nightmares somehow remind us that most of us were alive at the time, living happy lives elsewhere. Pol Pot is not a figure from the distant past and memories are not digital. Last summer, I went every day to the trial out by the air force base. The defendants are ancient, but the machinery of U.N. justice has tried its best to be merciless toward the leaders of the genocide. (Nevermind about the thousands of subordinates who did the actual killing. They cannot be dredged up, for some mysterious reason, and they have slipped back into the population unnoticed: a thousand killers walking the streets with their shopping bags.) As the technicalities dragged on, many impatient Khmers in the audience began to hiss and mutter angrily. Many of them were survivors or relatives of the dead. One day, I was invited to accompany a group of relatives from a small country town called Takeo, who had been invited by the U.N. outreach program to visit Tuol Sleng. The idea was to teach them about what might have happened to their loved ones and to show them the place where they might have died.

Many of these aging farmers had never been to the capital before, and Tuol Sleng to them was just a terrifying word. They arrived at the museum at 8 a.m., a large group anxious at first to have their pictures taken on the neat lawns under the shade of the frangipanis. But soon the mood changed. Tuol Sleng is filled with hundreds of mug shots taken by the captors as the prisoners were being processed prior to being "smashed." There are men, women, children--wildly beautiful young girls, old men, defiant teenagers with bloodied faces, disillusioned Party members who seem incredulous, small boys with cherubic eyes. Each one has a number slung around their neck (there is a famous Vann Nath panting of these ghastly photographic sessions). And there are pictures of the killed, too, each one with his or her throat cut, their chests cut open. There is a girl who threw herself out of a window to commit suicide. And there are the pictures by Vann Nath at every turn, exhibited here as if to corroborate the evidence. The farmers were as shocked by Vann Nath's paintings as by the portraits of the dead - perhaps more so.

Then it happened. I was standing next to a series of photos of prisoners, one of which is quite well known: It shows a young woman sitting next to her baby, her eyes turned helplessly toward the camera. Most of the portraits are marked "unknown" and this was no exception. The woman next to me was also studying this photo with excruciating intensity, and finally she let out an ear-splitting howl of grief. Tears streamed down her face. She recognized the girl with the baby. The farmers gathered round and the U.N. officials came up quickly with their notebooks; it sometimes happened t-hat a visitor recognized a dead relative, and it had happened now. The girl in the picture - the number - had a name after all, and she was the woman beside Me's sister-in-law. She had had no idea what had happened to her all those years before. The girl's name was Ouk Sareth. In the photo, she was 29. The sister-in-law's name was Nob Chim. I spent a little time with Nob Chim. She was 50 now and said she remembered "every moment" of the Khmer Rouge nightmare. Her hands shook with rage; she felt dizzy and had to sit down. She remembered she had built dams and farmed rice for Pol Pot. Ouk's husband had worked in the Ministry of Forestry and as an official had been targeted by the Khmer Rouge. He had been dragged behind a car to begin with - a little warning torture, if you like. Later, he disappeared altogether.

Ouk was sent to Tuol Sleng, it seemed, never to return. Her baby was killed as well. It is only by listening to people like Nob that you finally begin to fathom how casually the state can kill. Duch had signed Ouk's death warrant; she had shared this small prison with Vann Nath, whose Pol Pot busts stood piled up in a corner of the same room. How intimate and suffocating these interconnections were. Yet the anonymity of the regime's cruelty is strangely connected to the anonymity of its prime instigator, the man born as Saloth Sar.

It is that same anonymity that Vann Nath - consciously or otherwise - has captured in his pictures. As Nob wept, I couldn't help looking over at the impassive, smiling faces of Pol Pot that Nath had created to save his life. They explained nothing. Or did they? Vann Nath's pictures of Pol Pot are the most unnerving of all because he has captured something about the man without even wanting to. Pol Pot was always shadowy and inscrutable. He was always a smiling face in a humdrum photograph, an elusive eminence grise who ruled from behind the scenes. (During his reign, Western analysts had only been able to ascertain that Saloth Sar was Pol Pot by examining photographs of one of his state trips to China.) Inside Cambodia, many didn't know him even at the height of his power, even as they were about to die at his hands.

When Duch asked Vann Nath to put a name to a picture of Pol Pot, the confused artist said "Noun Chea." The director was highly amused, for Comrade Number One often "disappeared." He was always the puppet-master, the hidden engineer of human souls. And in Tuol Sleng one cannot help asking the question: Who was he? In a remarkable 1997 video interview with the American journalist Nate Thyer, the deposed dictator admitted, "I am not a very talkative person. … I am not a special person." He meant it. He mentioned with a shy smile that the French author Jacques Vergès had known him for 30 years "as a polite, discreet young man" but nothing more than that. Saloth was nothing if not stunningly ordinary. "Am I a violent person?" he liked to ask. How secretive the torturers always are, screened by legalisms and pseudonyms and euphemisms, their operations always carried out behind walls and closed doors - from where images can rarely travel. "If I had not painted water-boarding," Vann Nath told me one night, "people would probably not believe it had happened at all." He paused, "Let alone sawing people in half."

Labels: Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng, Vann Nath

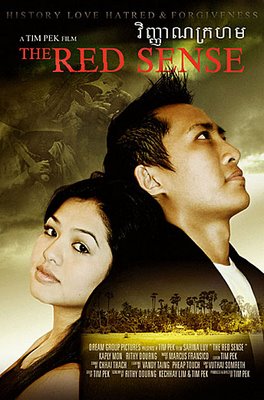

I've some news hot off the press for you: the first-ever Phnom Penh screening of Tim Pek's feature-film directorial debut, The Red Sense, will take place on Friday 24th April at 7pm at Meta House, next to Wat Botum. After receiving a Cambofest award when it got its first Cambodian screening in Siem Reap in December, Pek's made-in-Australia film about revenge and forgiveness when a women discovers the identity of the Khmer Rouge cadre who killed her father, will be very timely considering the ongoing Khmer Rouge Tribunal that begins again today in Phnom Penh. There were fears that the film's topic was too sensitive for some to be screened here, but it will now be shown afterall. You can find out more about the film here and I'll be bringing you additional news from The Red Sense camp closer to the screening date.

I've some news hot off the press for you: the first-ever Phnom Penh screening of Tim Pek's feature-film directorial debut, The Red Sense, will take place on Friday 24th April at 7pm at Meta House, next to Wat Botum. After receiving a Cambofest award when it got its first Cambodian screening in Siem Reap in December, Pek's made-in-Australia film about revenge and forgiveness when a women discovers the identity of the Khmer Rouge cadre who killed her father, will be very timely considering the ongoing Khmer Rouge Tribunal that begins again today in Phnom Penh. There were fears that the film's topic was too sensitive for some to be screened here, but it will now be shown afterall. You can find out more about the film here and I'll be bringing you additional news from The Red Sense camp closer to the screening date.Labels: Khmer Rouge, The Red Sense, Tim Pek

Labels: Em Theay

Labels: Preah Vihear

Substitutes and press cameramen snap the soon-to-be-victorious Phnom Penh Crown team before kick-off

Substitutes and press cameramen snap the soon-to-be-victorious Phnom Penh Crown team before kick-offLabels: Cambodia football

Labels: Kampi dolphins, Kratie

Labels: Kratie

Cambodia: Reporter's Log: Reporter Jenny Kleeman writes of her experiences making Cambodia: Selling the Killing Fields for Unreported World.

One of the most unsettling things about forced evictions is that it's impossible to know exactly when they are going to happen. For the 150,000 Cambodians currently under threat of displacement, that means living in a state of perpetual insecurity and fear. For a British crew hoping to document what a forced eviction looks like in Cambodia, it means my producer Andy Wells and I couldn't be sure if we'd be able to capture the key event in our film until it was happening right in front of us. After a few days of researching the story from our UK office, our contacts in Cambodia told us a large-scale eviction was imminent in the capital, Phnom Penh. The residents of Dey Krahorm had received their final eviction notice a month before, and the 120 families who remained on the site didn't seem to be reaching an agreement with the government over compensation for their land. The dispute had been going on for nearly four years. Even though it appeared to have taken a more serious turn in recent weeks, no one could tell us whether the residents would be forced from their land in a matter of days, weeks or even months. But we wanted to make sure we didn't land in Cambodia after it had taken place. We took a punt and decided to fly out as soon as our visas were ready – a week earlier than planned.

Once we'd touched down, it seemed our arrival was premature: the Dey Krahorm residents had managed to negotiate a stay of execution and the situation was quiet once again. In some ways, this was a relief for us: it meant we could get to know some of the key characters from Dey Krahorm - like Vichet Chan, the community representative - in relative calm. We got an insight into community life that we never would have captured had we arrived only a few days later. The news finally came that that the armed forces were poised to seize Dey Krahorm after we'd already done a full day's filming and were several hours away from the capital. It was as unexpected for us as it was for the residents. We managed to get back to Dey Krahom by 10pm. We had no idea what we were going to see that night, but once we'd spoken to Vichet and seen how distraught he was, it was clear that we could be about to witness the end of the community.

When the event you've come to film finally unfolds in front of you, you just keep filming. On the day that Dey Krahorm was raised to the ground, we worked for 30 hours straight. There was always another piece of the story to cover: from the construction of barricades before dawn and the brutality of the eviction itself to the impromptu press conference the government held on the rubble a few hours after it. By the time it was all over, we were truly exhausted. But for the people we'd been filming, it was only the beginning. They now faced the task of moving whatever they had managed to salvage to the relocation site, and trying to rebuild their lives away from the capital.

Labels: Channel 4, Unreported World

Meta House, here in Phnom Penh, will be hosting a Hanuman Film Night on Saturday 11 April to provide a taste of some of the diverse film and television work that the company has been involved in since it began in 2000. If you are planning a shoot, they're the ones to get things done here in the Mekong region, whether its scouting and managing locations, getting permissions, providing extras, building sets, transport, costume, you name it, they've done it on countless productions all over the area. Nick Ray and Kulikar Sotho, the two people behind Hanuman Films, will be on hand to introduce examples of their work, to answer questions and to give you an insight into what goes into making the slick documentary, film or advert that you see on the screen. The screenings will include Timewatch: Pol Pot (BBC, 2005) and Top Gear Vietnam (BBC, 2008) together with two shorts: part of the 2001 film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, the first Hollywood film for 36 years to be set in Cambodia and a recent Pepsi Commercial that went global.

Meta House, here in Phnom Penh, will be hosting a Hanuman Film Night on Saturday 11 April to provide a taste of some of the diverse film and television work that the company has been involved in since it began in 2000. If you are planning a shoot, they're the ones to get things done here in the Mekong region, whether its scouting and managing locations, getting permissions, providing extras, building sets, transport, costume, you name it, they've done it on countless productions all over the area. Nick Ray and Kulikar Sotho, the two people behind Hanuman Films, will be on hand to introduce examples of their work, to answer questions and to give you an insight into what goes into making the slick documentary, film or advert that you see on the screen. The screenings will include Timewatch: Pol Pot (BBC, 2005) and Top Gear Vietnam (BBC, 2008) together with two shorts: part of the 2001 film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, the first Hollywood film for 36 years to be set in Cambodia and a recent Pepsi Commercial that went global.Labels: Hanuman Films

Labels: Percy Dread, Upside Downside

Labels: Black Roots, Juvenile Delinquent

One of the classic reggae tunes that I was hooked into during my teens and twenties. This is The Natural-Ites and their legendary Picture on the Wall track that reverberated throughout the globe and is still popular today. The singers are Ossie Samms and Percy JP McLeod, backed by the Realistics band. The track was released in 1985 though the video looks like its from the latter part of the decade, most likely 1988 after Neil Foster had left the band. Enjoy. Read more.

One of the classic reggae tunes that I was hooked into during my teens and twenties. This is The Natural-Ites and their legendary Picture on the Wall track that reverberated throughout the globe and is still popular today. The singers are Ossie Samms and Percy JP McLeod, backed by the Realistics band. The track was released in 1985 though the video looks like its from the latter part of the decade, most likely 1988 after Neil Foster had left the band. Enjoy. Read more.Labels: Natural-Ites, Picture on the Wall

football with his sports teacher studies before joining the more-fancied Division 1 Royal Bodyguard team in 1993 - a move to a club that swept all before them in the top flight of Cambodian football during his half a dozen years there. 1993 also saw him make his international debut against a visiting USSR U/19 team, at the age of 21. It was in 1995 that Cambodia, with Sovannara as a regular in midfield, took its first tentative steps back into re-establishing its international presence. They took part in the SEA Games in Chiang Mai though their years of isolation clearly showed, conceding 32 goals and scoring none in their four matches. A year later, with Fickert (pictured) now at the helm, they took part in the Tiger Cup in Singapore, where they lost all four games, in the SEA Games in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta in 1997, where they won twice and narrowly missed the semi-finals, and finished third in the Presidents Cup in the Philippines the same year.

football with his sports teacher studies before joining the more-fancied Division 1 Royal Bodyguard team in 1993 - a move to a club that swept all before them in the top flight of Cambodian football during his half a dozen years there. 1993 also saw him make his international debut against a visiting USSR U/19 team, at the age of 21. It was in 1995 that Cambodia, with Sovannara as a regular in midfield, took its first tentative steps back into re-establishing its international presence. They took part in the SEA Games in Chiang Mai though their years of isolation clearly showed, conceding 32 goals and scoring none in their four matches. A year later, with Fickert (pictured) now at the helm, they took part in the Tiger Cup in Singapore, where they lost all four games, in the SEA Games in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta in 1997, where they won twice and narrowly missed the semi-finals, and finished third in the Presidents Cup in the Philippines the same year.Labels: Cambodia football, Prak Sovannara

I stopped by the Olympic Stadium at 7am this morning to get an update on the Cambodia national football team from coach Prak Sovannara, the man in charge of the country's football elite. My time was short and I didn't want to interrupt the squad's early morning training session, so I hope to catch him for a full interview sometime soon. In the meantime, I can exclusively reveal the comings and goings from the national squad of 22 players, who will form the nucleus of a reduced squad, which will travel to Bangladesh for the three AFC Challenge Cup Qualifying Group matches at the end of next month. Sovannara has been pretty ruthless in putting together his first squad for 2009, with nine players out, and nine players in. The new faces include three players each from the Hun Sen Cup finalists, Phnom Penh Crown and Naga Corp, so he's certainly selecting players who are already in good form.

I stopped by the Olympic Stadium at 7am this morning to get an update on the Cambodia national football team from coach Prak Sovannara, the man in charge of the country's football elite. My time was short and I didn't want to interrupt the squad's early morning training session, so I hope to catch him for a full interview sometime soon. In the meantime, I can exclusively reveal the comings and goings from the national squad of 22 players, who will form the nucleus of a reduced squad, which will travel to Bangladesh for the three AFC Challenge Cup Qualifying Group matches at the end of next month. Sovannara has been pretty ruthless in putting together his first squad for 2009, with nine players out, and nine players in. The new faces include three players each from the Hun Sen Cup finalists, Phnom Penh Crown and Naga Corp, so he's certainly selecting players who are already in good form.Labels: Cambodia football

It's been very quiet on the Cambodia national football team front in recent months following their involvement in the Suzuki Cup in early December. Three defeats left the team licking their wounds but it wasn't unexpected, they were the least-fancied team in the whole competition afterall. Aside from a few mutterings and talk of bringing Khmer nationals over from France to be considered for selection, there's been a dearth of football chatter, especially about the national team. In the background, national coach Prak Sovannara has simply got on with the task of lifting his team's spirits for the forthcoming AFC Challenge Cup Qualifying Group matches in Bangladesh. Initially scheduled for early April, they have been put back until the end of next month. The two-legged pre-qualifying decider between Macau and Mongolia has at last been scheduled for 9th and 16th April and the winner of that tie will go into the group matches in Bangladesh.

It's been very quiet on the Cambodia national football team front in recent months following their involvement in the Suzuki Cup in early December. Three defeats left the team licking their wounds but it wasn't unexpected, they were the least-fancied team in the whole competition afterall. Aside from a few mutterings and talk of bringing Khmer nationals over from France to be considered for selection, there's been a dearth of football chatter, especially about the national team. In the background, national coach Prak Sovannara has simply got on with the task of lifting his team's spirits for the forthcoming AFC Challenge Cup Qualifying Group matches in Bangladesh. Initially scheduled for early April, they have been put back until the end of next month. The two-legged pre-qualifying decider between Macau and Mongolia has at last been scheduled for 9th and 16th April and the winner of that tie will go into the group matches in Bangladesh.Labels: Cambodia football

The brickwork with this dvarapala has darkened over the centuries, though he still retains his immense strength

The brickwork with this dvarapala has darkened over the centuries, though he still retains his immense strength A gorgeously carved false door to a brick shrine at Bakong with two fierce lion-monster faces on either door panel just to deter wrongdoers

A gorgeously carved false door to a brick shrine at Bakong with two fierce lion-monster faces on either door panel just to deter wrongdoersLabels: Bakong, Roluos Group

Labels: Cambodia postcards

The style of the female form is in its early stages here at Bakong, not yet achieving the beautiful representations we see later at Angkor Wat for example

The style of the female form is in its early stages here at Bakong, not yet achieving the beautiful representations we see later at Angkor Wat for exampleLabels: Bakong, Roluos Group

Vishvakarma sits above a spewing kala on the lintel above. Figures on elephants rise out of the garland.

Vishvakarma sits above a spewing kala on the lintel above. Figures on elephants rise out of the garland. No fierce kala monster on this lintel, which is practically covered in small naga heads and a central god figure on a plinth. The top of the lintel is badly damaged.

No fierce kala monster on this lintel, which is practically covered in small naga heads and a central god figure on a plinth. The top of the lintel is badly damaged. You can just see the brick indentations above the lintel in this photo. The lintel itself is very badly eroded and in danger of collapse.

You can just see the brick indentations above the lintel in this photo. The lintel itself is very badly eroded and in danger of collapse. A more regimented lintel, in fine detail, particularly the gods in a line above the central narrative, though the lintel itself is damaged

A more regimented lintel, in fine detail, particularly the gods in a line above the central narrative, though the lintel itself is damaged Two large nagas form the ends of this lintel narrative, with a central Vishvakarma figure though the rest of the lintel is in poor condition, and in danger of breaking apart

Two large nagas form the ends of this lintel narrative, with a central Vishvakarma figure though the rest of the lintel is in poor condition, and in danger of breaking apart The final lintel, with naga ends, and a small god sitting on the kala, who is spewing forth the garlands from which dancing figures emerge

The final lintel, with naga ends, and a small god sitting on the kala, who is spewing forth the garlands from which dancing figures emerge This is one of the eight brick towers, in the northwest corner, on which these lintels are still in situ and represent some of the finest of their style in all Angkor

This is one of the eight brick towers, in the northwest corner, on which these lintels are still in situ and represent some of the finest of their style in all AngkorLabels: Bakong, Roluos Group

Lara, in the shape of Oscar-winning actress Angelina Jolie, was looking exceptionally lithe in a jet-black catsuit; the result, apparently, of several months spent bungee jumping, motorbike riding and martial-arts training. Closer examination proved impossible, alas: bystanders who strayed too close to the set were scared off by cries of "Oi, you! Keep back!" from a pack of hulking British minders. A few hours later, a group of daytrippers visiting the Bayon temple asked what all the trucks and cameras were for. The temple guide explained that they were filming a "love story". Had they been allowed closer to the set, the tourists would have witnessed something rather different: a grim-faced Lara expertly power-sliding her Land Rover through a morass of mud and water for the cameras. For director Simon West, there was never any question about who should play the lead. "Angelina was always my only choice, not even my first choice," he said. "It really was a one-horse race. If she didn't do it, I can't think who else would have been suitable."

Tomb Raider is the first film to be shot in Cambodia since Peter O'Toole played Lord Jim in the shadow of Angkor Wat in 1964 (one reason why West wanted to film there). Since then, however, the country has had other things on its plate: bombed by the US during the Vietnam war, ravaged by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge cadres in the 1970s, under occupation by Vietnamese troops in the 1980s and engulfed in civil war in the early 1990s, it has long been a no-go area for hardened backpackers, never mind unwieldy US film crews. Roland Joffe's The Killing Fields (1984), which described the background to the murder of some two million Cambodians by Pol Pot's regime, was filmed in neighbouring Thailand.

So the impact of Tomb Raider could be significant. If the film incarnation of Lara Croft is anything like as successful as her virtual counterpart, Cambodia can expect to enjoy something of a renaissance. Judging by the impact on tourism of the modestly successful Leonardo DiCaprio vehicle The Beach, which triggered a mini-invasion of Thailand's Phi Phi Leh island, Angkor could be swamped with tourists within a couple of years. For a time, though, it looked as if the Cambodian Tourist Board would have to postpone its recruitment drive, since the scenes to be filmed there nearly did not happen at all. Cambodia's film infrastructure is almost nonexistent, and much of the equipment had to be brought in from Thailand along a road that once ran through a Khmer Rouge stronghold. The road is littered with potholes and mines, and the transport crew - with the assistance of a minesweeper and the Royal Cambodian army - had to drive almost 30 trucks full of equipment along it. Inching its way towards Siem Reap, the gateway to the temples, the convoy often had to stop altogether while soldiers repaired the bridges ahead. "I can't wait until it is all over and they have gone home," said a frazzled transportation manager, gulping down a beer at the end of a particularly weary day on set. "Then I can get some sleep." He was, he said, being paid just $500 per week.

For most locals, however, used to the daily grind of negotiating washboard roads, the sum represents a king's ransom. Five hundred dollars equates to more than a year's wage for most Cambodians, who usually scrape by on one or two dollars a day. Susan D'Arcy, publicist with the Paramount film unit, said hundreds of Cambodians had been employed for Tomb Raider as extras or crew. Tens of thousands of much-needed dollars have been pumped into the local economy in hotel bills, mobile-phone rentals and wages. For translator Riem Sunsoley, who learned his English in a refugee camp on the Thai border, the film has been a huge boon, earning him $25 a day for five weeks. He is putting the money towards building an orphanage for the street kids who live around the temples. He is thankful to Hollywood, but says political peace is more important. "If politics does not go downhill then everything will develop. I hope more people from other countries will come to Cambodia," he said.

Just as valuable as the influx of cash, says Paramount, is the fact that Cambodians are witnessing first-hand how films are made. In the 1960s, Cambodia had a small but vibrant national film industry, largely thanks to the patronage of the country's movie-mad king, Norodom Sihanouk. Its chief output was formulaic, sickly-sweet love stories that were unashamedly cranked out for the masses. But Pol Pot single-handedly devastated the industry, killing most of the directors and actors who failed to flee the country in time. Since the ascension of former Khmer Rouge commander Hun Sen, the country's film industry has remained stagnant, stifled by the popularity of Hollywood and Hong Kong kick-and-chop movies. More importantly, Cambodia has no purpose-built cinemas. The old French colonial theatres have been converted into warehouses, shops or karaoke bars, and most movies are watched at home in the form of pirate videos. The fuss surrounding Ms Jolie and company, hopes the local artistic community, will revive interest in both film and film-making.

The film is also good news for the temples. The conservation authority responsible for preserving and protecting the complex is charging Paramount $10,000 per day for seven days. Much of the money will go back into caring for the temples themselves. Cambodia's conservationists have worked hard to avoid the outcry that followed the filming of a Mortal Kombat sequel in Thailand, where fight scenes were shot among the ruins of the Buddhist temples. Devout Buddhists were upset that violence had been allowed to disrupt what should have been a haven of peace. Conservationist Ashley Thompson, of Cambodia's Apsara temples authority, said the agency had worked extremely closely with Paramount to ensure that Cambodia's image was not sullied. "The film has made it past the censors here in Cambodia. What they told us is that there is violence, but that there are no guns and that Khmers [Cambodians] are not portrayed as violent people, but foreigners."

An extremely detailed contract was also drawn up to ensure that the temples would not be damaged in any way. However, the authorities decided against insisting on total control of what could be filmed. "Coming out of years of oppressive regimes, it seemed that censorship should not be something that we supported. Cambodia should be open, and violent films should be allowed, even if we don't like them," said Ms Thompson. Cambodia has found peace under strongman Hun Sen. But halfway through filming came an unwelcome reminder that the peace is all too fragile. On November 24, the capital, Phnom Penh, reverberated with the sound of gunfire when between 70 and 80 armed men laid siege to the city centre. Eight were killed and scores of suspects were rounded up. The alleged leader of what has been called an attempted coup was later arrested in Siem Reap - just a few hundred yards from where the Tomb Raider crew was staying. If the violence continues, salvaging Cambodia's tarnished image may be a task beyond even Lara Croft.

Labels: Lara Croft Tomb Raider

A brand new novel by Kim Echlin has this month been published in Canada. It's called The Disappeared and tells the story of love between a Canadian girl and a Cambodian student who returns to his country, never to be seen again. That forces the heroine to go in search of her lost love and to discover the truth behind the country of his birth. For Echlin, this is her third novel, as well as having experience as an arts documentary producer and writer for various publications.

A brand new novel by Kim Echlin has this month been published in Canada. It's called The Disappeared and tells the story of love between a Canadian girl and a Cambodian student who returns to his country, never to be seen again. That forces the heroine to go in search of her lost love and to discover the truth behind the country of his birth. For Echlin, this is her third novel, as well as having experience as an arts documentary producer and writer for various publications. You did not want to come with me to Tuol Sleng, Street 103, the hill of the poison tree.

I said, If you do not come I am going anyway. But I want you to come with me.

You said, No use.

Borng samlanh, come. I want to know what you know.

I put my arms around you and you let me and you said, You smell so good.

Tuol Sleng is raw.

It is easy to imagine this place transformed from museum back to extermination center in an hour. Everything left as it was. Burned walls. Bloodstained floors. Metal bed frames and shackles and electrical wires. A barrel of water to submerge a head. People walk over the courtyard graves before they know what they are walking on. There are hand-drawn signs, concrete block rooms, walls of photographs and glass cases of skulls. Paintings of the tortures, fingernails pulled out, men lying in rows on the classroom floors, shackled at the ankles, prisoners beaten and left in tiny cells. The eyes of those whose names disappeared stare from the walls. Their spirits are unprayed for because any family that might have prayed for them is dead.

Five thousand photographs of the dead of Tuol Sleng. Each picture refuses anonymity. Boy number 17. He has no shirt and they have safety-pinned his number into his skin. A small woman with the number 17-5-78 pinned on her black shirt stares into the camera and at the bottom of the photo a child’s small hand clings to her right sleeve.

Grief changes shape but it does not end.

It was a hot day and your forehead was damp. You said, When I first got back I came here to see if I could find pictures of anyone I knew. Tien’s whole family disappeared. I never found anyone who knows what happened to them. In the first months people wrote the names of those they recognized on the pictures. I found no picture to write on.

In Tuol Sleng a person is asked to stare. A person is asked to imagine clubbing someone to death, imagine attaching wires to genitalia, pulling a baby by the ankles away from its screaming mother and smashing its head against a tree.

I was numbed by this vision of a human being. I stood beside you and you were so far away that I could not touch you.

In Tuol Sleng a person can be torturer or tortured, a person can imagine a Pure system.

The Khmer Rouge said, Better to kill the innocent than to leave one traitor alive. This is the heart of Purity.

When I was writing this, I dreamed an old woman came to me and said, Help me to see into the darkness. In the dream I protested, How?

See the child. She has a strong jaw, but her eyes are a child’s eyes. Look into the pupils of her eyes. This is a body made vulnerable. This girl is available to wound. She does not even wear a number. She was not even worth a number. This is war. This is the darkness. This child too was murdered in Tuol Sleng.

Labels: Kim Echlin, The Disappeared

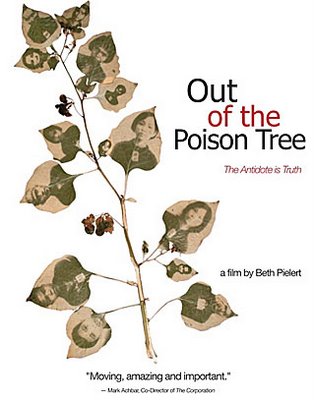

I've got a bee in my bonnet about films and documentaries that concentrate on Cambodia but haven't yet been shown here. There's been an explosion of films about Cambodia in recent years yet many have not been screened here for the general public, hence the reason why I arranged last night's Out of the Poison Tree screening at Meta House. It's an important film that gives Cambodians a voice about their own past, and with the Khmer Rouge trials about to begin in earnest, it was very timely and relevant. I was pleased with the size of the audience, all the seats were taken and the feedback on the film afterwards was very positive. I know Beth the director and Thida, the main subject, were very happy that their film was shown here and we now plan to show the film again in next month's Meta House programme. I took some screen captures including two of the most poignant moments in the film, where widow Lech Buon said she is still waiting for the return of her husband after 30 years, and 16-year old schoolgirl Davey Heng, who spoke so eloquently of her desires for justice. My thanks to Nico at Meta House for putting the film into the programme and I hope to get some more films shown there in future months.

I've got a bee in my bonnet about films and documentaries that concentrate on Cambodia but haven't yet been shown here. There's been an explosion of films about Cambodia in recent years yet many have not been screened here for the general public, hence the reason why I arranged last night's Out of the Poison Tree screening at Meta House. It's an important film that gives Cambodians a voice about their own past, and with the Khmer Rouge trials about to begin in earnest, it was very timely and relevant. I was pleased with the size of the audience, all the seats were taken and the feedback on the film afterwards was very positive. I know Beth the director and Thida, the main subject, were very happy that their film was shown here and we now plan to show the film again in next month's Meta House programme. I took some screen captures including two of the most poignant moments in the film, where widow Lech Buon said she is still waiting for the return of her husband after 30 years, and 16-year old schoolgirl Davey Heng, who spoke so eloquently of her desires for justice. My thanks to Nico at Meta House for putting the film into the programme and I hope to get some more films shown there in future months.Labels: Out of the Poison Tree

All smiles for hatrick hero Jean-Roger Lappe Lappe. You can tell he's an important asset - he's surrounded by security personnel

All smiles for hatrick hero Jean-Roger Lappe Lappe. You can tell he's an important asset - he's surrounded by security personnel  Phnom Penh Crown line up before the semi-final. Their team included national players Chan Rithy, Thul Sothearith and Teing Tiny.

Phnom Penh Crown line up before the semi-final. Their team included national players Chan Rithy, Thul Sothearith and Teing Tiny.  The other victorious semi-finalists, Naga Corp. They included national team captain Kim Chanbunrith and Sun Sovannarith.

The other victorious semi-finalists, Naga Corp. They included national team captain Kim Chanbunrith and Sun Sovannarith. Prak Sovannara (pictured) who was casting a watchful eye over members of his national team that were playing on the pitch below. With the AFC Challenge Cup qualifying group games coming up in Bangladesh very soon, he's already got his squad together, five days a week, putting them through their paces and expects to take a squad of 18 players to the three-game tournament next month. With three of last year's squad retiring, he's called six new players into the training camp, including two from Phnom Penh Crown and a striker from Naga. The matches will be against the hosts Bangladesh, Myanmar and the winners of Macau or Mongolia, who will play a pre-qualifying decider beforehand. If I can fit it in, I'll try to pay a visit to one of the national team's training sessions next week.

Prak Sovannara (pictured) who was casting a watchful eye over members of his national team that were playing on the pitch below. With the AFC Challenge Cup qualifying group games coming up in Bangladesh very soon, he's already got his squad together, five days a week, putting them through their paces and expects to take a squad of 18 players to the three-game tournament next month. With three of last year's squad retiring, he's called six new players into the training camp, including two from Phnom Penh Crown and a striker from Naga. The matches will be against the hosts Bangladesh, Myanmar and the winners of Macau or Mongolia, who will play a pre-qualifying decider beforehand. If I can fit it in, I'll try to pay a visit to one of the national team's training sessions next week.Labels: Cambodia football

Labels: Banteay Chhmar

The on-stage cast of Breaking the Silence; LtoR: Sakona, Tonh, Sovanna, Sotheary, Sokly, Sina, Vutha

The on-stage cast of Breaking the Silence; LtoR: Sakona, Tonh, Sovanna, Sotheary, Sokly, Sina, VuthaBut it is not just a play. Performing concurrently with the Khmer Rouge tribunals, "Breaking the Silence" is an appeal to Cambodians on both sides of the divide to speak up about what happened to them. "We want this to be in the service of the community," the Amrita's program director, Suon Bun Rith — whose grandmother lives in Takeo, just down the unpaved road from the performance space — said on a recent weekend. To this end, after each show, Suon or an emissary invited audience members to come forward and tell their stories. After the performance Sunday night, a man took the microphone. "Those who killed should come and see this show," he said, going on to say that he lived near a man who had killed several members of his family. He cited a scene in the play in which a former Khmer Rouge nurse apologizes for not helping a woman's dying father, explaining that she was trapped by circumstances. "Sometimes I try to talk to this man who killed my family," said the speaker. "But he just turns away." The play is very sympathetic to the perpetrators whose stories it tells, portraying them as victims in their own right. "We don't blame anyone," said Suon. "We want the community to start a dialogue."

The play premiered in Phnom Penh in late February, and then toured the provinces for eight performances, the last of which was Wednesday. This is unusual in a country in which nearly all cultural events take place in the capital or in Siem Reap (and was the cause of some pre-performance confusion for a food vendor in Takeo, who asked Suon if this was going to be a magic show put on by traveling medicine salesmen). The fact that it reaches isolated areas is part of what makes the play so powerful, according to Youk Chhang, who runs the Documentation Center of Cambodia and collaborated with Prins in the early stages of the project. "People talk about the tribunals, and of course that's good for the victims," he said. "But these people can't go to the trials." He was referring to the United Nations-backed Khmer Rouge genocide tribunal that began Feb. 17th in Phnom Penh. "This is something for them in the village. This is their stage and their court."

Chhang, who recently proposed to the minister of education that the play be included in school curriculums, dismissed the idea that a Western director might impose a Western understanding of trauma on the actors and audience. "Genocide is a crime against humanity," he said. Prins "isn't Dutch, she's human." He reconsidered, then said, "The title — 'Breaking the Silence' — that's foreign. But we don't call it that, in Khmer." While Amrita translates the title more or less directly, Chhang said that only a handful of educated city dwellers refer to it that way. "The villagers call it 'Khmer Rouge Stories' or 'Pol Pot Stories,'" he wrote in an e-mail message. For Chhang, the play holds up a mirror for the audience — something, he said, that was important for the victims' process of healing from the trauma they have experienced. He also cited the play's emphasis on Buddhist philosophies of forgiveness. Then he added, "I think of myself as a strong person, a bone collector. A relentless genocide investigator. But the first time I saw this, I cried."

The four main actresses were all victims of the Khmer Rouge regime. Morm Sokly, in her 40s, plays a 7-year-old girl in one vignette who, famished, steals the family's rice. "My own experience gives me a depth of understanding for what we play on the stage," she said. "The girl who steals the rice — I have that guilt in myself." The younger members of the production said that they learned from the play, as well. "Before, as a Cambodian, I knew my mom and her family had had very sad experiences and lost family members," said Chey Chankeytha, 24, a classically trained dancer who choreographed the show. "But I had never heard from the people who worked in the killing fields. From the play, you see how it felt to be a Pol Pot child soldier. We should know both sides."

The play's current run ended this week under a full moon in a field across from a rice paddy in Kandal Province with a small but rapt core audience (several middle aged women had returned for a second night in a row). Barring funding problems, the performance will resume in November after the rainy season with another eight shows in the Battambang and Siem Reap regions. Given the reactions of those who choose to speak after the performances, "Breaking the Silence" seems to hit a nerve. After the Saturday night performance in Takeo ended, a gray-haired woman took the microphone. Crying softly, she said, "This was my story I saw on the stage. The kids might not believe it, but it's true."

Labels: Breaking the Silence

Full of figures, fifteen in total with two lion-like creatures known as gajasimha at the ends and Vishvakarma sitting on the kala. There are also naga heads and a row of deities at the top.

Full of figures, fifteen in total with two lion-like creatures known as gajasimha at the ends and Vishvakarma sitting on the kala. There are also naga heads and a row of deities at the top. A much less intense lintel narrative with far fewer figures though essentially the same design with Vishvakarma the central god

A much less intense lintel narrative with far fewer figures though essentially the same design with Vishvakarma the central god Much of this lintel is badly eroded though figures riding elephants remain clear, as do the deities high above

Much of this lintel is badly eroded though figures riding elephants remain clear, as do the deities high above The figures high above are less defined and the lintel is full of floral scrolling, with Vishvakarma again sat regally on the grinning kala

The figures high above are less defined and the lintel is full of floral scrolling, with Vishvakarma again sat regally on the grinning kala Quite a vivid lintel though partly disfigured. There are many figures either side of Vishvakarma on a plinth - no kala at all - with a multitude of naga heads and two human figures at the ends of the entwined garlands

Quite a vivid lintel though partly disfigured. There are many figures either side of Vishvakarma on a plinth - no kala at all - with a multitude of naga heads and two human figures at the ends of the entwined garlands Detail from a corner of the final lintel, showing a small figure bearing the weight of the lintel and above a human figure has replaced the makara-cum-gajasimha

Detail from a corner of the final lintel, showing a small figure bearing the weight of the lintel and above a human figure has replaced the makara-cum-gajasimhaLabels: Bakong, Roluos Group

Labels: Jimi Lundy, The Red Sense

Labels: Out of the Poison Tree, Phnom Penh Post

Director Tim Pek's The Red Sense movie received its premiere in Melbourne, Australia a year ago but has only been screened in Cambodia once to-date, at the CamboFest in Siem Reap in December. I'm now hoping to get it screened in Phnom Penh, so in the meantime, to whet your appetite, here's a trailer from the feature-length movie.

Director Tim Pek's The Red Sense movie received its premiere in Melbourne, Australia a year ago but has only been screened in Cambodia once to-date, at the CamboFest in Siem Reap in December. I'm now hoping to get it screened in Phnom Penh, so in the meantime, to whet your appetite, here's a trailer from the feature-length movie.Labels: The Red Sense

Meet Song Kosal: One afternoon, at age six, Song Kosal’s life was changed forever. While working in the rice paddies with her mother in Bavel village, Battambang, she stepped on a landmine. Kosal’s right leg was severely injured and had to be amputated. She now walks with the assistance of a single crutch.

Meet Song Kosal: One afternoon, at age six, Song Kosal’s life was changed forever. While working in the rice paddies with her mother in Bavel village, Battambang, she stepped on a landmine. Kosal’s right leg was severely injured and had to be amputated. She now walks with the assistance of a single crutch. When she was 12, with the support of the Jesuit Refugee Service, Kosal became active in the Cambodian Campaign to Ban Landmines. After campaigning extensively in Cambodia, she traveled to Vienna, Austria in 1995 and spoke to government officials at the Convention on Conventional Weapons. She was the first person to sign the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty in Ottawa, Canada, and was present in Oslo, Norway, when the ICBL and Jody Williams were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. "Sometimes I dream that I have two legs again and I run freely in the ricefields, feeling the grass under my toes," says Kosal. "I really wish that soon my friends and I can play without danger, with no more mines in our fields."

Kosal has taken her message to Spain, Australia, Japan, Canada, United States, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Mozambique, Morocco, Belgium, Switzerland and France. She has met with heads of states and dignitaries around the world including the King of Cambodia, Queen of Spain, Queen of Jordan, and the US Secretary of State. She has given addresses at the Hague Appeal for Peace and Meetings of States Parties. She created the Youth Against War Treaty and presented the over 263,000 signatures collected to the Bush administration in 2001 in an effort to influence the US to join the Mine Ban Treaty. That same year Kosal was named ICBL Youth Ambassador.

As ICBL Youth Ambassador, Kosal represents youth campaigners and survivors at events worldwide. Kosal has succeeded in putting a face to the many lesser-known child landmine survivors around the world. In her role as ICBL Youth Ambassador she continues to raise awareness around the world, while pursuing her university studies in Phnom Penh. Song Kosal has dedicated her life to creating a world free of landmine dangers.

Labels: Song Kosal

Labels: Eric de Vries, Jerry Redfearn, Karen Coates, Stan Feingold

Finer detail from the lintel above. The central figure is Vishvakarma sitting astride kala who is spewing garlands, upon which 4 figures are riding elephants. There are sea makaras at each end, lots of floral scrolling and a line of acolytes at the very top of the lintel.

Finer detail from the lintel above. The central figure is Vishvakarma sitting astride kala who is spewing garlands, upon which 4 figures are riding elephants. There are sea makaras at each end, lots of floral scrolling and a line of acolytes at the very top of the lintel. Labels: Bakong, Roluos Group

Filmmaker Beth Pielert's beautiful and moving film follows Thida Buth Mam and her two sisters back to Cambodia to find out more about the disappearance of their father, Buth Choen and to hear first-hand from Cambodians about the necessity for justice, a trial and forgiveness. Perhaps the most poignant plea for justice comes from a teenage schoolgirl, Davey Heng, standing amongst her classroom peers, in a flood of tears, but determined to state her point of view. As the Khmer Rouge Tribunal readies itself for the trial of Comrade Duch, this film is aptly timed for the voice it gives to ordinary Cambodians as well as well-known figures like Youk Chhang and Aki Ra. Archive footage and music from acclaimed Long Beach artist praChly complete the picture.

Filmmaker Beth Pielert's beautiful and moving film follows Thida Buth Mam and her two sisters back to Cambodia to find out more about the disappearance of their father, Buth Choen and to hear first-hand from Cambodians about the necessity for justice, a trial and forgiveness. Perhaps the most poignant plea for justice comes from a teenage schoolgirl, Davey Heng, standing amongst her classroom peers, in a flood of tears, but determined to state her point of view. As the Khmer Rouge Tribunal readies itself for the trial of Comrade Duch, this film is aptly timed for the voice it gives to ordinary Cambodians as well as well-known figures like Youk Chhang and Aki Ra. Archive footage and music from acclaimed Long Beach artist praChly complete the picture. A faded picture of Thida Buth Mam's father, the subject of their return to Cambodia to search for the truth

A faded picture of Thida Buth Mam's father, the subject of their return to Cambodia to search for the truthLabels: Out of the Poison Tree

I haven't been around much to catch any of the on-going Hun Sen Cup football competition being played in Phnom Penh in recent weeks but this coming Saturday is the semi-final stage at the Olympic Stadium here in the capital, and I hope to catch some of the action. The two games will be played in the afternoon and will see league champions and cup holders Phnom Penh Crown (formerly Phnom Penh Empire, pictured above) take on last year's 4th-placed Preah Khan Reach, while the unfancied Phuchung Neak will do well to stop Naga Corp. In the quarter-finals, Phuchung Neak provided the shock of the competition when they knocked out the Defense Ministry on penalties. However, the military team had themselves to blame by putting their national striker Khim Borey on the bench from the start. Naga also needed spot-kicks to defeat Ranger FC (previously Khemara Keila), who had national striker Kouch Sokumpheak in their ranks and who netted five times in the previous round but couldn't repeat the feat in this game. The other semi-finalists are the cup favourites Phnom Penh Crown, who beat Build Bright one-nil - they boast the national defensive partnership of Thul Sothearith and Teing Tiny, as well as left-footer Chan Rithy in their line-up - whilst Preah Khan Reach knocked Post Tel aside 3-0. Preah Khan have four members of the national squad in their ranks together with legendary veteran striker Hok Sochetra. The Hun Sen Cup Final will be played in Phnom Penh on 28 March.

I haven't been around much to catch any of the on-going Hun Sen Cup football competition being played in Phnom Penh in recent weeks but this coming Saturday is the semi-final stage at the Olympic Stadium here in the capital, and I hope to catch some of the action. The two games will be played in the afternoon and will see league champions and cup holders Phnom Penh Crown (formerly Phnom Penh Empire, pictured above) take on last year's 4th-placed Preah Khan Reach, while the unfancied Phuchung Neak will do well to stop Naga Corp. In the quarter-finals, Phuchung Neak provided the shock of the competition when they knocked out the Defense Ministry on penalties. However, the military team had themselves to blame by putting their national striker Khim Borey on the bench from the start. Naga also needed spot-kicks to defeat Ranger FC (previously Khemara Keila), who had national striker Kouch Sokumpheak in their ranks and who netted five times in the previous round but couldn't repeat the feat in this game. The other semi-finalists are the cup favourites Phnom Penh Crown, who beat Build Bright one-nil - they boast the national defensive partnership of Thul Sothearith and Teing Tiny, as well as left-footer Chan Rithy in their line-up - whilst Preah Khan Reach knocked Post Tel aside 3-0. Preah Khan have four members of the national squad in their ranks together with legendary veteran striker Hok Sochetra. The Hun Sen Cup Final will be played in Phnom Penh on 28 March.Labels: Cambodia football

Hats off to local newspaper The Cambodia Daily today with a couple of stories that caught my attention and which deserve a quick mention. The first is a new documentary film that will open today for its premiere at the International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights in Geneva, titled Finding Face. It's all about the case of teenage karaoke video star Tat Marina, who was doused in acid during an attack at the end of 1999. It cites the story of Marina's years of plastic surgery and her decision to never return to Cambodia, while the film also focuses on the spate of other attacks on women in the months that followed. No-one has ever been brought to justice for the attack on Marina. Skye Fitzgerald and his wife Patti Duncan created the 80-minute documentary but have no plans to show it in Cambodia for fear of reprisals against some of its subjects who still live here. Find out more at Spin Films. Fitzgerald's previous focus on Cambodia was in his 2007 film Bombhunters, whilst Tat Marina's story was also used as the basis for the graphic novel Shake Girl, which you can read about here.

Hats off to local newspaper The Cambodia Daily today with a couple of stories that caught my attention and which deserve a quick mention. The first is a new documentary film that will open today for its premiere at the International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights in Geneva, titled Finding Face. It's all about the case of teenage karaoke video star Tat Marina, who was doused in acid during an attack at the end of 1999. It cites the story of Marina's years of plastic surgery and her decision to never return to Cambodia, while the film also focuses on the spate of other attacks on women in the months that followed. No-one has ever been brought to justice for the attack on Marina. Skye Fitzgerald and his wife Patti Duncan created the 80-minute documentary but have no plans to show it in Cambodia for fear of reprisals against some of its subjects who still live here. Find out more at Spin Films. Fitzgerald's previous focus on Cambodia was in his 2007 film Bombhunters, whilst Tat Marina's story was also used as the basis for the graphic novel Shake Girl, which you can read about here.Labels: Finding Face, Nhem En, Skye Fitzgerald

I am back in the office today, with my repaired skin and everyone says I look healthy again. It's a little too early to celebrate as I'm still on medication but at least I can be seen in public again without small children running away shouting and screaming hysterically. And when I get around to shaving my face, I might just begin to look human again. The improvement in such a short space of time has been dramatic and if people didn't eat whilst reading this blog, I would post before and after photos, but I wouldn't do that to even my worst enemy as I did look pretty horrific at the end of last week. The skin man in Singapore deserves a lot of credit.

I am back in the office today, with my repaired skin and everyone says I look healthy again. It's a little too early to celebrate as I'm still on medication but at least I can be seen in public again without small children running away shouting and screaming hysterically. And when I get around to shaving my face, I might just begin to look human again. The improvement in such a short space of time has been dramatic and if people didn't eat whilst reading this blog, I would post before and after photos, but I wouldn't do that to even my worst enemy as I did look pretty horrific at the end of last week. The skin man in Singapore deserves a lot of credit.

Labels: Phnom Penh, Pochentong

Q. Where did the idea for the film come from?

Q. Where did the idea for the film come from?Labels: Beth Pielert, Khmer Rouge, Out of the Poison Tree, Thida Buth Mam

This skin man knows his stuff. He'd like me to stay another 15 days to find out what caused it but that's too long, so I hope to get back to Phnom Penh in the next day or two. How rude of me not to introduce the skin man. Meet Dr Lee Chui Tho (pictured), consultant dermatologist at Mt Elizabeth Hospital. As I've already implied, he is a top man in his field and diagnosed my condition within moments of me walking through his door. He promised to treat and clear it and so far he's kept to his promise. If you ever need the services of a guy who knows skin, he's your man. Click here. [End of medical update]

This skin man knows his stuff. He'd like me to stay another 15 days to find out what caused it but that's too long, so I hope to get back to Phnom Penh in the next day or two. How rude of me not to introduce the skin man. Meet Dr Lee Chui Tho (pictured), consultant dermatologist at Mt Elizabeth Hospital. As I've already implied, he is a top man in his field and diagnosed my condition within moments of me walking through his door. He promised to treat and clear it and so far he's kept to his promise. If you ever need the services of a guy who knows skin, he's your man. Click here. [End of medical update] The gopuram entrance way to the Sri Veeramakaliamman temple, dedicated to the goddess Kali, located on Serangoon Road

The gopuram entrance way to the Sri Veeramakaliamman temple, dedicated to the goddess Kali, located on Serangoon Road Labels: Chinatown, Little India, Singapore

Labels: Little India, Singapore

Labels: Angkor

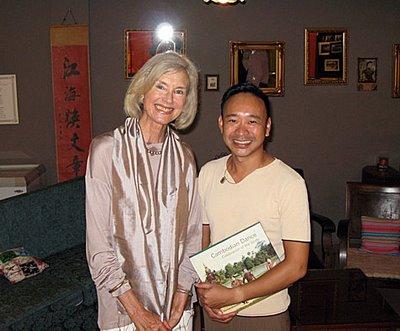

Em Theay and in Denise's words: "she's my favourite person and someone whom I revere for her courage, strength, inner and outer beauty."

Em Theay and in Denise's words: "she's my favourite person and someone whom I revere for her courage, strength, inner and outer beauty." Denise with Prince Sisowath Tesso, the great-great-grandson of King Sisowath, and Secretary of State at the Tourism Ministry