The Mekong River at Luang Prabang

The Mekong River at Luang Prabang

Kate Quill in today's Times Online from London, penned this piece on her recent visit to Laos and spending time on the Mekong River.

A slow, ponderous journey up the Mekong -

by Kate Quill (Times, UK) With its haunting light and primeval landscapes, the Mother River in Laos takes you on a journey of dark dreamsI am standing in the grounds of an elegant French colonial building in the middle of Luang Prabang, Laos. It’s 1pm, the sun is pressing down heavily on my head and the tropical humidity is bringing an unladylike sweat to my upper lip. I’m exchanging pleasantries on the immaculate lawn, but struggling to maintain my composure. I drop like a stone suddenly, and come to moments later slumped on the grass as a line of white-jacketed staff come dashing across the lawn with water, iced towels and smelling salts. There is much commotion as a bottle is waved under my nose and my forehead delicately dabbed. A man takes my arm and escorts me back inside, mixes me a curing tonic and instructs me to go back to bed. The shutters are closed, soothing but firm words delivered, and I am left alone to convalesce in my cool white room.

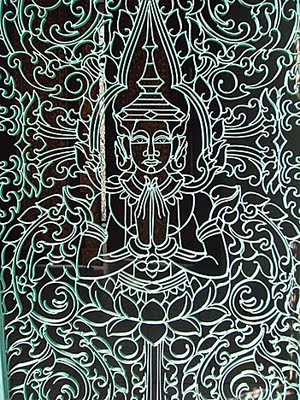

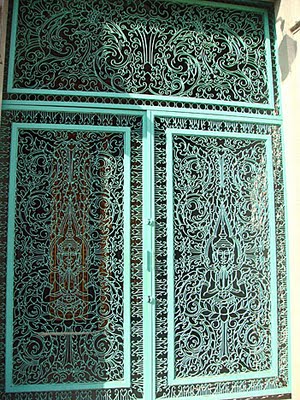

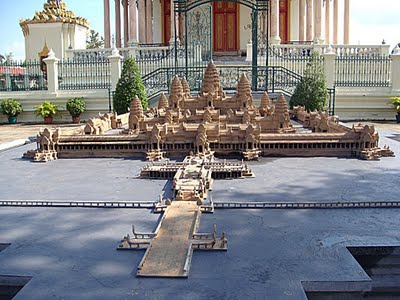

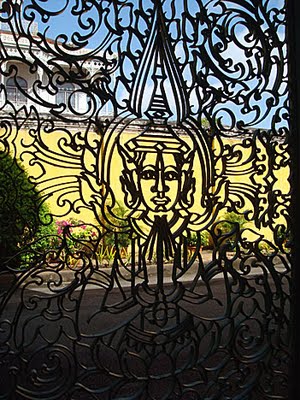

I arrived here by boat two days previously; a slow, ponderous journey up the Mekong, during which I heard many stories from the boatmen about spirits. The Laotians are Buddhist, but their religion is infused with something much darker and older: animism — a belief that places and things have spirits that must be placated. I can’t help but think of this, lying on my sickbed in the latest top-notch hotel to open in Luang Prabang, because until recently this was the city hospital. Amantaka is like all its Aman brethren — lean, thoroughbred, with a monastic-style luxury, but beyond the expensive linen and fine French wines its medicinal “spirit” could not be more alive. It feels like a calm, benign asylum. People sit in its quiet gardens and whisper. Malaria wouldn’t dare show its face in here. So I lie in my room, cursing the poisoned meal I ate in town the night before, and read about the sadder fate of Henri Mouhot, the 19th-century French explorer who rediscovered the great Angkor Wat temples of Cambodia in 1860, and met a lonely, untimely death of jungle fever only a few kilometres from Luang Prabang a year later.

In Cambodia Mouhot had been indifferent to the Mekong, but by the time he had reached Luang Prabang he had fallen in love with it, describing it sentimentally as “an old friend” who possessed “an excess of grandeur”. I couldn’t agree more. Even though I’m in a bewitching city full of bicycles, temples, monks and flowers, part of me is still sitting on the careworn boat that brought me here. Less than an hour into the two-day journey from Huay Xai, by the Thai border, with the ink on my Laos visa scarcely dry, the Mekong began to work its stealthy magic on me. Its history has been eventful and violent, and its 21st-century fortunes may be equally momentous, as Laos, China and Thailand consider building more dams along it. The Thais know the Mekong as “mother river”. The author Colin Thubron, recalling the Vietnam War, referred to it as “this river of evil memory”. At 4,350km (2,700 miles), it is South-East Asia’s longest river, running from Tibet through China, Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

As we chugged away from the border we filed through lush tropical countryside. The Thai side was busier and more prosperous, Laos noticeably less cultivated. This is one of the poorest countries in the world, with an average wage of about $1 a day and, with only 7 million people, it is sparsely populated. At the end of the rainy season the Mekong is full and wide and trembling with treacherous currents. Our boat had a battered steel hull — there’s a good reason for that. Our captain, Thitnat, who has been navigating this part of the Mekong for 15 years, turned a cunning, snakelike path to avoid huge slabs of rock and sandbanks just beneath the surface. Every year he must carefully reconnoitre the same route to check how the sandbanks have shifted as the seasons change.

As we progressed, the landscape grew more dramatic and the atmosphere in the rugged terrain had an unsettling stillness. The river in Apocalypse Now was based on the Mekong and our course felt as though it might be plugged straight into Colonel Kurtz: the mountains were high and covered in impenetrable, tendril-strewn jungle; a mysterious mist settled on their upper reaches. The weather was like a moody teenager: one minute an oppressive cloud loomed above; an hour later we slid through a bright, hallucinatory light. Then, round a bend in a river, and everything appeared opaque and hazy. A rainstorm hit out of nowhere, lashed the boat furiously, and vanished.

Tourism up this part of the Mekong began to take off in 1995, but, even so, the river was quiet in mid-October. Time slowed; I couldn’t recall life ever being as unhurried as this. There was no mobile phone reception. We felt cut off from the world. I could see no roads or cars, only fishermen in their slender longtails casting their nets, water buffalo basking in the shallows, and the occasional passenger boat. The waterborne exile was broken by a stop at a typical Mekong village: a collection of wood and bamboo huts built on stilts, with semi-naked children splashing about at the river’s edge, smiling and waving. This one, Gon Dturn, is used to visitors. Our boat, the Pak Ou, stops here every week.

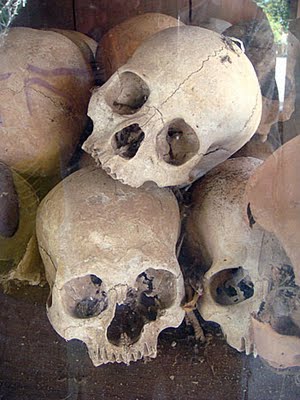

The women displayed their handwoven scarves and the children giggled as we photographed them. No one spoke any English, and it seemed, to our eyes, shockingly poor. But for a rural Laotian village it is relatively wealthy, Toua, our first mate, told us. It had electricity and the inevitable satellite dishes have followed. To our astonishment it even had a “corner shop”, run by Chinese, that sold cheap gadgets and plastic household items. “The Chinese are opening shops like this all over Laos,” Toua said. Laos’s dismal record on public healthcare (there is none) was evident in the badly deformed foot of a boy. Polio? Or unexploded ordnance? Laos is the most bombed country on Earth, thanks to America’s “secret war” in the Sixties and Seventies. Of the two million tonnes of bombs that fell, about a third failed to explode and are still sitting waiting to claim lives and limbs.

On we went, until the day began to fade. In the twilight, we stopped at Luang Say Lodge near Pak Beng, a riverside trading village. The electricity, which powered dim, yellow light, was turned off at 11pm. As night closed in, the darkness was a crescendo of cicadas, other insects and the occasional squawking bird. I sat outside my wood and bamboo hut and stared down at the river, but could see nothing. Everything was lost in a deep supernatural darkness. All around me the jungle throbbed. We were hardly far from civilisation — the village was 1km away — but how easy it was to believe in primeval spirits here.

The Mekong doesn’t permit cool, rational detachment, as Mouhot discovered. Its beauty can be intensely moving, its dense forests mysterious and foreboding, its clouds of mist and shifting light hypnotic and troubling. Your skin seems to get thinner and your emotions rise to the surface. In the sleepy hours after lunch, my mind settled on the past, on people I have lost, and I became aware that some painful knots I carry around with me were unravelling. By the time we reached Luang Prabang, I felt spaced out by it all. Laos does a lively, illegal trade in opium, but who needs it here? The humid, aromatic air is like an opiate, and so many things are not, at first, what they seem.

As we approached our mooring we didn’t even know that Luang Prabang was there — how often can you say that upon arriving at a new city? This beautiful place, bursting with flowers and greenery, is protected by Unesco and has no high-rises. It lies like a reclining Buddha, hidden by trees. We climbed a broad stone stairway cut into the steep riverbank, and found a road and gently humming city beyond. The journalist Jon Swain wrote in River of Time, his love letter to Indochina: “There is something about the Mekong which, even years later, makes me want to sit down beside it and watch my whole life go by.” You don’t need to give up five years of your life, or live through Indochina’s appalling wars and revolutions, as Swain did, to feel that. Two days on a boat and the Mekong will be under your skin for ever.