Thursday, July 31, 2008

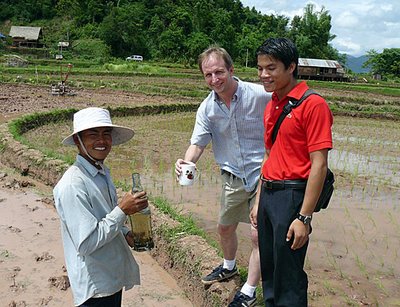

In and around Champasak

A Thai view on ANM

Damn the begrudgers! - The Bangkok Post, Horizons

Less than a year old, the Angkor National Museum in Siem Reap has already come in for a lot of flack; we paid a visit recently to see what all the hullabaloo was about.

With Angkor Wat in its backyard (or is it the other way around?), the town of Siem Reap is a revolving door for tourists eager to gaze on the remnants of the majestic architecture of a once-powerful civilisation. The sheer size of this temple complex is, in itself, overwhelming. And while a stroll through the site is always an eye-popping experience, the surviving structures are, quite literally, shells of their former glorious selves. All the statuary and other sacred objects that escaped the attention of looters have long since been removed for safe-keeping. Most of the artefacts were transferred to the National Museum in Phnom Penh where lack of display space means that a lot of them are kept locked away in warehouses. Enter the Angkor National Museum, a $15 million project which is divided into eight themed zones and covers an area of 20,000m2; it is, remarkably, Siem Reap's first full-scale museum.

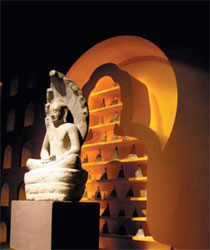

It was officially opened late last year but finishing touches are still being put to the so-called Cultural Mall, a building adjacent to the museum proper which features a host of gift shops, restaurants and even a spa - a one-stop centre for those in search of sustenance, souvenirs and retail therapy. The modern facilities in the museum include numerous interactive presentations; visitors are free to manipulate the controls of audio-visual displays which come with commentary in a choice of seven languages (English, Cambodian, French, Thai, Japanese, Chinese and Korean). The first of these presentations is encountered at the very start of your tour, in an 80-seat briefing hall where you are shown a brief video, a primer for everything you'll encounter during your visit. The first gallery you enter isn't even counted among the eight aforementioned zones, but it certainly doesn't pale in comparison; in fact it's one of the highlights of the whole place. A special exhibition aptly entitled "1,000 Buddha Images", for it features (you guessed it!) 1,000 Buddha statues ranging from the pre-Angkor (1st to 8th century AD) and Angkor (8th to 14th century) periods to the present day. The oldest dates from the 6th century. The juxtaposing of the different eras allows one to see the marked variations in style. The pre-Angkor images show strong Indian influences and are carved mostly from sandstone while those from the Angkor period utilise both sandstone and bronze. The post-Angkor Buddhas on display here are made from wood and various metals and exhibit many similarities to statues one might come across in a Thai wat. A striking feature of this hall is that all four walls have rows of niches housing hundreds of Buddha statuettes.

As one penetrates farther into the museum one progresses through Cambodia's illustrious past, touching on aspects of its history, culture, society, traditional costumes and spiritual beliefs. There are in excess 1,400 authentic artefacts in all, some, unfortunately, in poor condition. A focal point of interest is the Angkor Wat zone where one can pore over a fascinating, miniature scale model of the temple complex and watch a video explaining the methods used in its construction. Although the museum's government-appointed curator, Chann Charouen, is a Cambodian national, there has been much mumbling and grumbling of late about the folks behind this project. The Thai folks, that is. Yes, it may raise some eyebrows, but this museum is in fact the brainchild of a Thai company, a fact which has, understandably, drawn the ire of some Cambodians. (One can only hope that the ongoing stand-off over Preah Vihear/Khao Phra Viharn does not add fuel to the fire). Critics of the museum have accused the Thai investors of exploiting Cambodia's heritage to pocket a profit. And all sorts of wild rumours have been flying around. According to one (patently untrue) canard, it is mandatory for all visitors to walk through the official gift shop at the end of their tour. But then what new museum, aquarium or zoo in this day and age - Thai-run or otherwise - doesn't sport a souvenir shop with overpriced key chains and stuffed toys?

The Thai investors insist that their intentions are pure; that they set up this museum to showcase the rich cultural heritage of the Khmer Empire. They point out that, according to the terms of the agreement they signed with Phnom Penh officials, once their 30-year lease on the site and the exhibits (on loan from other museums in the country) expires, the Cambodian government will become the legal owner of the museum. Many still suspect the investors' motives, however, and this is hardly surprising given that the fingerprints of Thai entrepreneurs are to be found all over Siem Reap. No one seems to be making a fuss about these Thai-run businesses but then none of them are claiming to be a national museum, are they? All that aside, some areas of the museum could do with a bit of tweaking. Many of the artefacts on display still lack proper descriptions and much of the compound is under-lit, making it a bit hard on the eyes sometimes. Despite what its detractors say, the museum does offer an educational and aesthetically pleasing experience and - let's face it - it's still the only place in Siem Reap where you can see what once embellished the interiors of all those mesmerising ruins.

Colonial elegance

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Arnfield's one-woman show

The Gymnast brings Cambodian torment to life - by Chris Collett (MetroLife)

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, took control of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. During the next four years, the regime reduced the country to a slave state and was responsible for the death of an estimated 1.7million people through executions, compulsory urban evacuation and forced labour. Watching news reports about Cambodian refugee camps at that time had a lasting effect on Jane Arnfield, whose new one-woman show, The Gymnast, directed by DV8 founder member Nigel Charnock and premiering at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, is inspired by this dark episode in the country's history. 'When the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh, I was nine,' says Newcastle-based theatre artist Arnfield. 'I remember the Blue Peter Appeal for the refugees, and I remember collecting bottle tops. I was shocked by what I saw and it obviously made a deep impression.'

Though childhood memories were the spark for the show, The Gymnast is the result of extensive research. In January, Arnfield spent a month at the Documentation Center Of Cambodia, an organisation dedicated to bringing the former leaders of the Khmer Rouge to justice. While there, she was able to work closely with its Victims Of Torture project. 'They allowed me to accompany them on field trips and offered me the opportunity to interview people,' says Arnfield. 'I interviewed a man called Bou Meng, who is one of the six survivors of S-21, which was an infamous Khmer Rouge prison.' Although Arnfield learnt much about the atrocities that took place under the Khmer Rouge from first-hand testimonies, she stresses that the show is not a verbatim catalogue of pain and suffering. 'The last thing I want to do is just take people's stories and put them onstage,' she says. 'It is about culpability, responsibility and ultimately about loss - and how we deal with loss.'

An assemblage of spoken word, physical theatre, music, recorded voice and sound, the show juxtaposes her personal experiences of growing up in the late 1970s - the title refers to the gymnastic certificates Arnfield was working towards at school at the time - with the events taking place in Cambodia. 'The starting point for me was that while the West was disco dancing, this country was almost being taken back to medieval times,' she continues. 'I find the contrast fascinating.' Described by Arnfield as a 'multilayered experience', disco songs from the period are interwoven with material such as President Nixon ordering the obliteration of Cambodia. Some of the content is self-explanatory; other aspects are less directly relevant, but everything, including Neil Murray's wardrobe set design, is there for a reason. 'I read an extract that John Pilger had written when he first landed in Phnom Penh,' Arnfield explains. 'When he was walking down the road, he saw a wardrobe, and as he looked at it a child emerged from inside and ran off down the road. He had obviously been living in there. I thought that was a really powerful image.' Committed to investigating the legacy of the Khmer Rouge and other despotic regimes, Arnfield sees The Gymnast as the beginning of a larger project. 'It is the first of many planned pieces using Cambodia as a starting point,' she says. 'Over the next ten years I want to investigate what it is like to come from a traumatic situation.'

Note: Jane Arnfield is Artist in Residence at the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (DC-Cam) and recently completed her research for this piece in a one-month trip, which provided the opportunity to work closely with Sophearith Choung and the Victims of Torture Project as well as with Youk Chhang, Director of DC-Cam, artist and one of TIME magazine’s 100 Heroes and Pioneers.Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Bookshelf news

More new books on Cambodia are about to arrive on the bookshelf. These include two publications from the University of Hawai'i Press. Up for release this month is People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today, a 320-page study into the role of religion in Cambodia and its impact on the society and how its been shaped by the past. The editors are Alexandra Kent and David Chandler. Last month saw Beyond Democracy in Cambodia: Political Reconstruction in a Post-Conflict Society released, again 320 pages and edited by Joakim Ojendal and Mona Lilja. Written by a broad mix of Khmer and non-Khmer researchers, this study looks at how Cambodia has handled democracy and reconstruction since major conflict ended in the last decade. The Univerity of Hawai'i Press are certainly doing their bit to expand the bookshelves on Cambodian studies. Already this year they have released two books about the role of women in Cambodia, namely Khmer Women On the Move by Annuska Derks and Lost Goddesses by Trudy Jacobsen. One other book to mention, Cambodia - Culture Smart! will be out in October. Written by Graham Saunders, 168 pages and published by Kuperard, it will offer an insight into the culture and society of Cambodia, with do's and don'ts, taboos and so on. And coming very soon will be my exclusive review of the brand new, not yet available in the bookshops, Rough Guide to Cambodia 3, which has just landed on my desk. I'm looking at it now, as I type. Does it float my boat? How does it shape up to its big rival, the new Lonely Planet Cambodia? More later.

More new books on Cambodia are about to arrive on the bookshelf. These include two publications from the University of Hawai'i Press. Up for release this month is People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today, a 320-page study into the role of religion in Cambodia and its impact on the society and how its been shaped by the past. The editors are Alexandra Kent and David Chandler. Last month saw Beyond Democracy in Cambodia: Political Reconstruction in a Post-Conflict Society released, again 320 pages and edited by Joakim Ojendal and Mona Lilja. Written by a broad mix of Khmer and non-Khmer researchers, this study looks at how Cambodia has handled democracy and reconstruction since major conflict ended in the last decade. The Univerity of Hawai'i Press are certainly doing their bit to expand the bookshelves on Cambodian studies. Already this year they have released two books about the role of women in Cambodia, namely Khmer Women On the Move by Annuska Derks and Lost Goddesses by Trudy Jacobsen. One other book to mention, Cambodia - Culture Smart! will be out in October. Written by Graham Saunders, 168 pages and published by Kuperard, it will offer an insight into the culture and society of Cambodia, with do's and don'ts, taboos and so on. And coming very soon will be my exclusive review of the brand new, not yet available in the bookshops, Rough Guide to Cambodia 3, which has just landed on my desk. I'm looking at it now, as I type. Does it float my boat? How does it shape up to its big rival, the new Lonely Planet Cambodia? More later.

Free-for-all

Cambodia's Forgotten Temples Fall Prey To Looters - by Guardian Unlimited

The three freshly dug holes under the two arching palm trees measured a metre by about half a meter, and about half a meter deep. A few fragments of what appeared to be centuries-old clay pots were scattered around the excavation site, seemingly discarded as worthless in the hunt for more valuable treasure. "We find new holes every week," said Ndson Hun, a farmer living in the nearby village of Phoum Snay. "The demand [for artefacts] is as great as ever, so people keep digging." No one knows the extent of the riches at Phoum Snay, an unremarkable Cambodian village about 40 miles north-west of Angkor Wat, the complex of 100 9th to 15th-century Buddhist temples seen as among the world's architectural wonders. But, unlike at Angkor Wat, there are no heritage police here, no Unesco staff, and no local authorities to guard the site. As the latest holes testify, anyone wishing to pillage the remaining hidden riches will encounter few obstacles. Experts fear the decades-long looting for artefacts across Cambodia is now so rampant there will soon be little left outside the splendors of the Unesco world heritage site at Angkor. "Almost all sites of antiquity and temples far from towns are being destroyed," said Michel Trenet, the undersecretary of state at Cambodia's culture and fine arts ministry. "Naturally, the priority for us is to protect the Angkor sites and then think about the others. But we don't have enough guards and people are not motivated to protect their heritage. Cambodia is becoming a cultural desert."

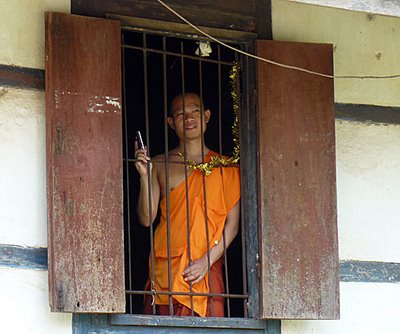

Phoum Snay is a classic example. On its discovery, almost three years ago, the site was thought to have been a mass grave for victims of the Khmer Rouge, the communists who ruled from 1975-79 and under whose regime some 1.7 million people were executed or died from disease and starvation. Then, when iron-age artifacts, including weapons, jewelery, pots and trinkets, started appearing, the site was reassessed as the burial ground of an ancient army. The researchers moved in, and digging started. Thousands of items were found. Yet little was done to secure the area and antiques traders - people mainly from neighboring Thailand, say villagers, and seeking to sell Khmer treasures abroad - now have virtual free rein. Their success is shown by the regularity with which Khmer artifacts appear at auction around the world. At any one time, dozens of Khmer "treasures" are on offer on the eBay auction website. Poverty and greed are considered the two main motivations behind the looting. Monks living in a temple half a mile from Phoum Snay believe the villagers are involved in the illicit digging, despite protestations by Ndson Hun and his friends. "The villagers are doing it because they are so poor," said Moy Sau, clad in his traditional saffron-coloured robes. "They don't respect their heritage because they can't afford to turn down an offer of a few dollars for a night's work." Chea Vannath, president of the Centre for Social Development, says that the average annual income in Cambodia is about £155 a year - much lower in rural areas. "Protecting our cultural heritage is a luxury," she said. "People are fighting to survive so they don't know better." Moy Sau does not dare warn the authorities about the looting: "As a monk I cannot do anything because I rely on the villagers for my food."

Preservation

Even if he raised the alarm, that might not ensure the artifacts' preservation since government officials and members of the security forces are also involved in the trade, widespread reports suggest. A stone carver based a few miles away, in Phumi Rohal, who was too afraid to give his name, said some provincial government officials last month asked him to build a base for a "half Buddha" that one of their bosses had acquired. "I was suspicious even though they had lots of letters and said it would be kept in a temple," he said. "But I did it because I'm afraid of the authorities. Us little people can do nothing against them." With the country's legal system being so corrupt, the "dark forces", Mr Trenet says, are too powerful, even for him. A tour of Toul Ta Puon, known as the Russian market, in the capital, Phnom Penh, proves his point, with shops packed with tall cabinets full of artifacts. Bronze-age axe heads and rings sell for less than £15. One intricately carved 11th-century, long-necked water jar was £30. The shopkeepers appear motivated only by money and refuse to lower their prices, even for Mr Trenet, though most recognise him. "I would like to buy all [the artifacts] for the museum. But my salary is only [£155] a month so what can I do?" he says.

More tears on the way

Where will it all end? In tears methinks. Nevertheless, Roy Hill has been hard at work again in remastering and releasing yet another two CD's, this time its the songs of Cry No More that get the airing. Roy and his buddy Chas Cronk were the mainstays of Cry No More during their ten-year stint together, and the two CD's that have just been released are their 1986 Cry No More Live at the Mulberry Tree session, and their imaginatively-titled Cry No More album from 1987. Both are definitely worth getting hold of - believe me. If you've yet to enjoy the delights of Roy Hill and Cry No More, you are missing out on top-quality pop and razor-sharp song-writing at its very best.

Where will it all end? In tears methinks. Nevertheless, Roy Hill has been hard at work again in remastering and releasing yet another two CD's, this time its the songs of Cry No More that get the airing. Roy and his buddy Chas Cronk were the mainstays of Cry No More during their ten-year stint together, and the two CD's that have just been released are their 1986 Cry No More Live at the Mulberry Tree session, and their imaginatively-titled Cry No More album from 1987. Both are definitely worth getting hold of - believe me. If you've yet to enjoy the delights of Roy Hill and Cry No More, you are missing out on top-quality pop and razor-sharp song-writing at its very best. The Mulberry Tree experience comes complete with the pub's Choir who knew every word of every song and play a big part in complementing the comedic singing of Mr Hill, the bass brilliance of Cronk and the keyboard wizardry of Nick Magnus. With fifteen tracks you certainly get your money's worth. The CD's tracks are: Radio; I Love Roxy; Dancing in the Danger Zone; Fashion; Man Overboard; Every Single Time; On Holiday; Don't Leave Me Here; Tears on the Ballroom Floor; Jenny Takes A First Look at Life; Marion Jones; Jimmy & Johnnie; Cry No More; Looking for Something Mr Templar; Wooden Heart.

The Mulberry Tree experience comes complete with the pub's Choir who knew every word of every song and play a big part in complementing the comedic singing of Mr Hill, the bass brilliance of Cronk and the keyboard wizardry of Nick Magnus. With fifteen tracks you certainly get your money's worth. The CD's tracks are: Radio; I Love Roxy; Dancing in the Danger Zone; Fashion; Man Overboard; Every Single Time; On Holiday; Don't Leave Me Here; Tears on the Ballroom Floor; Jenny Takes A First Look at Life; Marion Jones; Jimmy & Johnnie; Cry No More; Looking for Something Mr Templar; Wooden Heart.The altogether more expensive affair, Cry No More, was released by EMI in August 1987 and produced by Richard Gotherrer, Jeffrey Lesser and David Richards. It didn't make them millionaires but its top drawer nonetheless. The CD's ten tracks are: Cry No More; You Don't Hurt; Tears on the Ballroom Floor; Recipe For Romance; Oh Bessie; Real Love; Every Single Time; Marion Jones; Hit The Big Drum; Don't Leave Me Here.

To get copies of both CD's at ten British pounds apiece plus postage & packing, email deepdene@fsmail.net and keep your fingers crossed. Roy has recently released two solo CD's, Hello Sailor and Fun With Dave, which are excellent, and has a few solo shows lined up on 7 Sept (at Brentford Festival), 11 Sept (at the Milton Arms, Southsea) and 17 Oct (at the Turks Head in Twickenham). The Cry No More annual Christmas Show and Farewell Appearance has also been booked for the Turks Head on 27 Dec. It's not really their farewell appearance, well, I don't think so, its just Roy's attempt at humour.

Monday, July 28, 2008

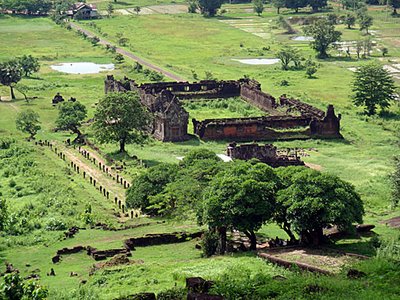

Scenic shots at Wat Phu

Sunday, July 27, 2008

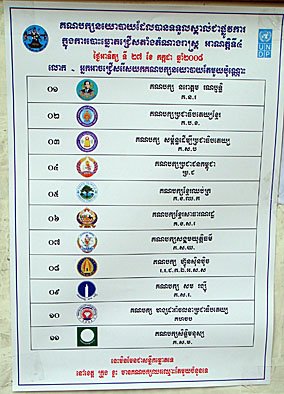

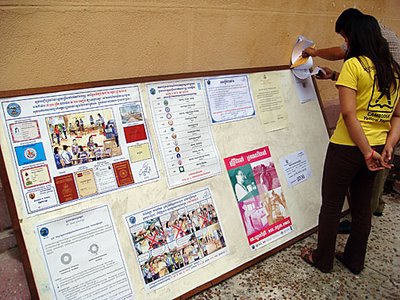

Cambodia votes

Above, two of Cambodia's 8.1 million voters check the electoral list for their names and registration numbers before voting at one of the five polling stations at Wat Lanka in Phnom Penh this afternoon. Cambodia's adult population went to the polls for the fourth time today since the UN-brokered peace of 1993, and everyone expects the CPP party and the current Prime Minister Hun Sen to extend and consolidate their 23-year stint in power. With many of the city's workers returning to their home provinces to vote, much of Phnom Penh was as quiet as a mouse, with the majority of shops staying closed.

Above, two of Cambodia's 8.1 million voters check the electoral list for their names and registration numbers before voting at one of the five polling stations at Wat Lanka in Phnom Penh this afternoon. Cambodia's adult population went to the polls for the fourth time today since the UN-brokered peace of 1993, and everyone expects the CPP party and the current Prime Minister Hun Sen to extend and consolidate their 23-year stint in power. With many of the city's workers returning to their home provinces to vote, much of Phnom Penh was as quiet as a mouse, with the majority of shops staying closed.Postscript: Early indications suggest a landslide victory for CPP with the opposition vote split between the majority Sam Rainsy Party and the Human Rights Party, with the royalist parties losing voters in droves. Shenanigans in Phnom Penh meant many voters names were not on the electoral role. I spent Sunday afternoon watching my Bayon Wanderers team-mates play football at the Old Stadium. My leg is giving me some grief after last weekend's exertions so I was sidelined and if the swelling doesn't recede tomorrow I will visit the doctor for a check-up.

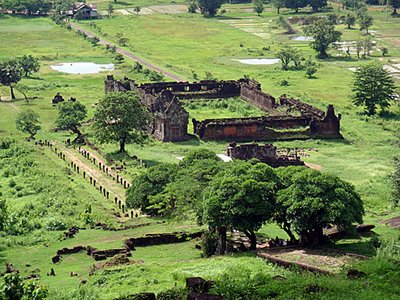

Solitude at Banteay Prei

Citadel of the Forest

An entrance pavilion sits on top of the covered gallery that encircles the main sanctuary area that is littered in large sandstone blocks

An entrance pavilion sits on top of the covered gallery that encircles the main sanctuary area that is littered in large sandstone blocksForest Sanctuary

There's more to Krol Ko

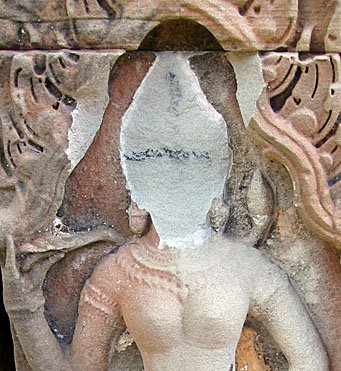

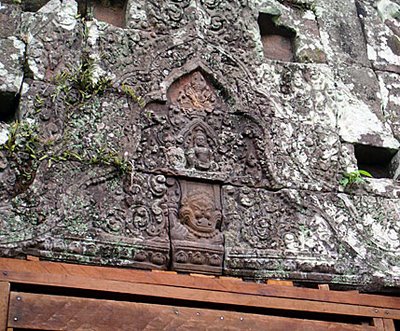

This pediment represents Krishna lifting Mount Govardhana with one hand to protect the grateful farmers and animals shown on the lower registers from the wrath of Indra

This pediment represents Krishna lifting Mount Govardhana with one hand to protect the grateful farmers and animals shown on the lower registers from the wrath of Indra Lokeshvaras of Krol Ko

This Lokeshvara is standing on a lotus flower supported by hamsas and is pouring water from a flask over a kneeling figure

This Lokeshvara is standing on a lotus flower supported by hamsas and is pouring water from a flask over a kneeling figureSaturday, July 26, 2008

How stupid am I?

Postscript: I made it back to Phnom Penh by 6.30pm, exactly 5 hours on the road courtesy of the Rith Mony bus company. Beggars can't be choosers when all seats are sold elsewhere but at least they got me back home and the ticket cost just over six dollars. All seats were taken and small plastic chairs filled the gangway too as the bus maximized its passenger count. One of those seated by me was a soldier who regaled the passengers with his tales of daring do at Preah Vihear. Phnom Penh looked very quiet on arrival, 8.1m people are registered to vote at some 15,000 polling stations across the country tomorrow and that means lots of shops are 'shuttered up' and the owners and personnel have gone back to their village for a couple of days.

All alone at Banteay Thom

Friday, July 25, 2008

More secrets

Hidden secrets of J-VII

The eastern entrance to the gopura and main sanctuary of Krol Ko

The eastern entrance to the gopura and main sanctuary of Krol KoThursday, July 24, 2008

ANM update

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Eating pancakes

Nearly finished...

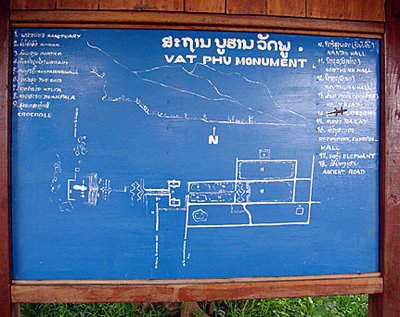

Can you spot it? - its a crocodile carved into a large boulder, behind the sanctuary, believed to date from Angkorean times

Can you spot it? - its a crocodile carved into a large boulder, behind the sanctuary, believed to date from Angkorean timesIt never rains...

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

Spean-mania

The 30 kilometre section of Highway 6 between Kompong Kdei and Damdek is populated with more than half a dozen of the laterite Angkorean-age bridges (or 'speans') that you can see in these photos. In a rare moment of sanity, the modern-day road builders actually took into account the historical significance of these bridges and deliberately paved the highway around them, and even rebuilt them in most cases, to preserve them for posterity. Most people just sail past them, unaware of their existence, so I thought I'd post a couple of photos just so that you can keep an eye open for them next time you take that section of highway. They pale into insignificance compared to the mighty Spean Praptos that you can see at Kompong Kdei, but in their own small way, they too represent the golden age of bridge-building in Khmer history.

Finally, I had dinner with friends at the Shadow of Angkor restaurant tonight and the place was heaving. Everyone has been telling me that visitor numbers are sparse at the moment, so most of them must've been in the Shadow! I was passing on the good news of the latest 'our pick' in the new edition of the Lonely Planet guide to the owner Seng Hour and it seems word has already got out amongst the travelling fraternity. Not a spare seat in the house, both in the restaurant and the guesthouse upstairs.

Monday, July 21, 2008

Invitation to a premiere

Film Director Steve McClure has issued an open invitation to all to join him for the Cambodian premiere of the feature documentary, Rain Falls from Earth: Surviving Cambodia's Darkest Hour. It's a story of courage, a story of survival and a story of eventual triumph over the genocidal regime that was responsible for the deaths of up to 2 million Cambodian people. The voices of many survivors are heard as they convey their thoughts, ideas and emotions - the very things they were forced to abandon in the killing fields of Cambodia. Narrated by Academy Award nominated actor, Sam Waterston, this film gives a voice to those lives that were senselessly lost. Visit here for more information about the film. The premiere will take place on Saturday 9 August at 7.30pm at the Meta House on Street 264 in Phnom Penh. Admission is free and a Q&A with Steve McClure will follow the film's screening.

Film Director Steve McClure has issued an open invitation to all to join him for the Cambodian premiere of the feature documentary, Rain Falls from Earth: Surviving Cambodia's Darkest Hour. It's a story of courage, a story of survival and a story of eventual triumph over the genocidal regime that was responsible for the deaths of up to 2 million Cambodian people. The voices of many survivors are heard as they convey their thoughts, ideas and emotions - the very things they were forced to abandon in the killing fields of Cambodia. Narrated by Academy Award nominated actor, Sam Waterston, this film gives a voice to those lives that were senselessly lost. Visit here for more information about the film. The premiere will take place on Saturday 9 August at 7.30pm at the Meta House on Street 264 in Phnom Penh. Admission is free and a Q&A with Steve McClure will follow the film's screening.It looks like I will be making the trip north to Siem Reap tomorrow for a few days on business. It will give me the chance to reunite with some friends who I haven't seen for a few months and I hope to return to the Angkor National Museum for an updated visit and viewing of their collection. I also want to try and fit in a visit to a couple of quiet corners of Angkor that I haven't seen for a few years, but it will depend on work commitments. It will also mean that I can't go to football training this week, which is a good thing at the moment, as every part of my body is screaming at me to take a rest! I forgot to mention that I watched the 2-hour thunderstorm that flooded the capital's streets yesterday afternoon, from the comfort of the restaurant at the Dara Reang Sey Hotel. I hadn't seen the two sisters, Reangsey and Dara, who manage the hotel for a few months, so it was catch-up time and they fed me as they always do - they repeatedly tell me I look too thin and then proceed to ply me with as much food and drink as I can manage. They are lovely people and I'm proud to call them my friends.

Sunday, July 20, 2008

Sunday soccer

During my dinner at the Red Orchid, I watched a television programme which was devoted to reading out names of donors who had pledged amounts as little as $5 to a fund being organized to pay for food and supplies for the Cambodian soldiers currently on duty at the Preah Vihear stand-off. That's about the gist of it as I could make out...the public dipping into their pockets to send the troops parcels of supplies - an interesting take on keeping the nationalism aspect of this spat foremost in the minds of the audience. Thai troops have occupied the pagoda at the top of the mountain for a few days now and talks tomorrow are aimed at defusing the situation, which has even overshadowed the run-up to next weekend's general election in Cambodia. By the time I'd finished my plate of spaghetti, the total amount of pledges had risen to $50,000. Then it was time for a massage to relax my weary bones at the end of a tiring day.

Saturday, July 19, 2008

The central sanctuary

The thirst for knowledge

If you don't know me by now, then my thirst for new books on Cambodia is insatiable. So I was overjoyed to learn of two brand new books and one revised edition, soon to be published by River Books in Bangkok. Top quality books are the staple diet of this publishing house and the two new arrivals look set to continue that trend. In Beyond Angkor, Helen Ibbitson Jessup and Ang Choulean get their heads together to explain the journey, geographically and chronologically, of the Khmer civilization, from Phnom Da through Sambor Prei Kuk and onto Roluos before the expansion into Laos and present-day Thailand and the grandeur of Angkor Wat, Bayon, Preah Khan, Ta Prohm and many more temples in the Angkor region and beyond. With photos by John Gollings (over 250 colour photos), Jessup and Choulean are the perfect pair to bring this 220-page journey to life. I await their collaboration with bated breath.

If you don't know me by now, then my thirst for new books on Cambodia is insatiable. So I was overjoyed to learn of two brand new books and one revised edition, soon to be published by River Books in Bangkok. Top quality books are the staple diet of this publishing house and the two new arrivals look set to continue that trend. In Beyond Angkor, Helen Ibbitson Jessup and Ang Choulean get their heads together to explain the journey, geographically and chronologically, of the Khmer civilization, from Phnom Da through Sambor Prei Kuk and onto Roluos before the expansion into Laos and present-day Thailand and the grandeur of Angkor Wat, Bayon, Preah Khan, Ta Prohm and many more temples in the Angkor region and beyond. With photos by John Gollings (over 250 colour photos), Jessup and Choulean are the perfect pair to bring this 220-page journey to life. I await their collaboration with bated breath. Hot on their heels will be Vittorio Roveda and Yem Sothorn's Buddhist Painting in Cambodia, a 200-page, 300-photographs tome that will document and discuss the rich Buddhist cultural heritage of Cambodia. This detailed study will explain and illustrate, analyze and review episodes of Buddha's life as well as the mural paintings to be found at 70 pagodas visited by the authors during four years of research. This book is a must-have record before some of these paintings are lost forever. Vittorio Roveda is a master of Khmer iconography and his Khmer Mythology - Secrets of Angkor will be revised with new stories and new sites later this year. 224-pages and with over 260 illustrations, Roveda's work details the legends and motifs to be found at 21 major temples in Angkor, explaining in intricate detail the stories and features behind the reliefs of Hindu gods and Buddhist themes. All three books will be in my shopping cart for sure.

Hot on their heels will be Vittorio Roveda and Yem Sothorn's Buddhist Painting in Cambodia, a 200-page, 300-photographs tome that will document and discuss the rich Buddhist cultural heritage of Cambodia. This detailed study will explain and illustrate, analyze and review episodes of Buddha's life as well as the mural paintings to be found at 70 pagodas visited by the authors during four years of research. This book is a must-have record before some of these paintings are lost forever. Vittorio Roveda is a master of Khmer iconography and his Khmer Mythology - Secrets of Angkor will be revised with new stories and new sites later this year. 224-pages and with over 260 illustrations, Roveda's work details the legends and motifs to be found at 21 major temples in Angkor, explaining in intricate detail the stories and features behind the reliefs of Hindu gods and Buddhist themes. All three books will be in my shopping cart for sure.

Roveda on iconography

Defying dynasties - by Manote Tripathi, The Nation, Thailand, Nov 2007

An expert in Buddhist art questions the Hindu influence in four of Angkor's temples

There's always something to be discovered in Khmer art. Just ask renowned Angkor scholar Vittorio Roveda. In a recent Siam Society lecture, Roveda questioned the accepted Hindu attribution of the Angkor temples of Banteay Samre, Chau Say Tevoda, Thomannon and Beng Mealea and presented evidence of underlying Buddhist iconography. A former palaeontologist who obtained his first degree in the 1950s, Roveda switched interests in the 1980s and went on to obtain a second doctorate in art history and archaeology from London University's School of Oriental and Asian Studies. He has spent the past two decades studying Buddhist iconography and the mythology of Khmer art from the eighth to the 13th centuries and has published five books including Khmer Mythology, Sacred Angkor and Preah Vihear Guidebook. "I'm interested in Buddhist iconography because I love Buddhist paintings and the Buddha's teachings, especially the institution that 'you are what you think'. That's so true," he says.

Roveda is particularly interested in Khmer history covering the 12th and 13th centuries, a period characterised by dynastic rivalries. The era also marks the Khmer Empire's transition from Hinduism to Mahayana Buddhism in the 1300s, and then back to Hinduism before the eventual rise of Theravada Buddhism in the 1400s. A systematic defacing of Buddha images occurred in this period, especially after the reign of Jayavarman VII, who was in power from 1181 to sometime after 1206, he says, pointing to the various Buddhist elements in Angkor temples that were subsequently replaced by Hindu-inspired sculpture. According to Roveda, defacing religious images was motivated more by politics than religion, and as the throne changed hands from one dynasty to the next, iconoclasm became a major political tool, one that was used until the reign of Jayavarman VIII (1243-1295).

A devout follower of Mahayana Buddhism, Jayavarman VII is considered the last of the great kings of Angkor because of the building projects carried out under his reign. He built the new capital of Angkor Thom and at its centre constructed the Bayon as the state temple, with its towers bearing faces said to be those of the Boddhisattva Lokeshvara (Avalokiteshvara). Under his rule of less than 40 years, hundreds of monuments were built. Other edifices constructed during his reign include the temples of Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei and Preah Khan. However, art historians point out that his monuments are considered artistically inferior to those in earlier periods because most of the buildings were built in haste. The abrupt construction of Buddhist temples was probably for two reasons. First, the king was trying to introduce a new religion to a predominantly Hindu population. Second, the need to construct so many temples reflected his determination to legitimise his rule, as there may have been other contenders closer to the royal bloodline.

Three reigns later, the empire reverted to Hinduism, with Jayavarman VIII launching a campaign to destroy more than 10,000 Buddha images in the kingdom. Under his rule, many Buddhist temples built by Jayavarman VII were converted into Hindu temples. Jayavarman VIII was deposed and succeeded by his son-in-law Srindravarman (1295-1308) who was a follower of Theravada Buddhism. "The defacing occurred after a change of religion or ruling dynasty in the Khmer court. At the centre of religious iconoclasm is power distribution. When Jayavarman VIII took the throne, he wanted to destroy anything that referred to Jayavarman VII. He destroyed not just Buddha images, but also paintings. What we're talking about here concerns the affairs of the upper-crust of society, royalty itself. We don't know anything about the people of Cambodia, only the aristocracy," he says.

Roveda adds that the power struggle in the Khmer court appears Hindu-inspired. In the Angkor period, the Khmer imported the Hindu caste system, with the elite court clergy (or the purohito) considered more powerful than the king. "Conflict often arose because the purohito wanted to be made king, to be appointed the chakravarty, or the king of the kings. So what happened was that the king needed the purohito and the purohito needed the king to stay in power. The relationship between the king and the purohito was so strong that the king would give his daughter or sister to the purohito as wife so as to create another royal bloodline that consisted of priests and royals. Religion thus became an intimate part of the king's power," he says. Having visited most of the Khmer temples, Roveda offers some tips on how to distinguish the Buddhist from the Hindu temples. "If there are Buddha statues and reliefs at the centre of the temples, they are [originally] Buddhist. Temples that have inscriptions at the entrance are usually not Buddhist."

My first meeting with author Vittorio Roveda in January 2006

Friday, July 18, 2008

Flight connections

Expanding the travel options in Cambodia and once again, reconnecting the south coast with the popular tourist destination of Siem Reap, Siem Reap Airways have announced plans to launch a new route from 13 October (two days before my birthday, please note), connecting Siem Reap and Sihanoukville with four flights a week, leaving on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. This will allow travelers to kick-off their tour at

Back in Phnom Penh, my own resurrected football-playing career is starting very slowly. Severe blisters on the soles of my feet after my first training session under tennis court floodlights put me out of action for a week and after last night's session, I've picked up a groin strain that could keep me out of playing my first game for Bayon Wanderers on Sunday afternoon! I will make a decision on whether to risk it just before the 2pm kick off time. Bayon are a team of ex-pats here in the city - though Khmers are welcome to join - and they usually manage to field two teams every weekend for friendly matches against local teams. I've just realized that my last competitive game was in April 2001, so no wonder my body is telling me to take it easy - I didn't appreciate that its been 7 years since I last kicked a ball in anger.

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Close-ups

Above: Vishnu rides his mount, Garuda. The bird-man grasps a multi-headed naga in either arm, while he steps upon one-headed nagas who, rearing up, obscure his legs. Vishnu has four arms and is standing on the shoulders of his mount. This lintel is above the northern door of the sanctuary. White patches on this lintel are lichens, not paint. Above: Our popular friend and minor god, though he seems to appear more often on lintels than all of the main gods added together, Vishvakarma - architect of the gods - makes an appearance on this lintel, above a kala in munching mode, as he makes a meal out of a foliage branch. This is one of the most popular lintel representations to be found at Wat Phu and many other temples of the same era.

Above: Our popular friend and minor god, though he seems to appear more often on lintels than all of the main gods added together, Vishvakarma - architect of the gods - makes an appearance on this lintel, above a kala in munching mode, as he makes a meal out of a foliage branch. This is one of the most popular lintel representations to be found at Wat Phu and many other temples of the same era. Above: This is a rishi at the foot of a colonette at the main sanctuary. The word rishi mens seer, singer of sacred verses, inspired poet or generally, a sage. They all wear a long pointed beard and this representation, in meditation, reminds me of the regiments of rishis at the foot of upright columns at Angkor Wat.

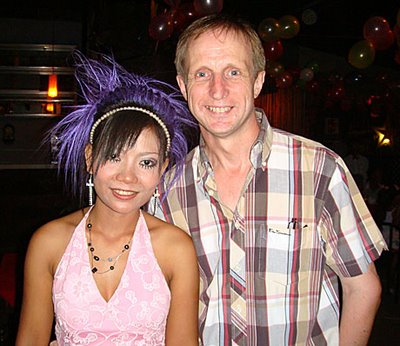

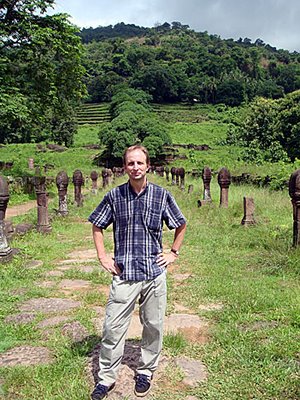

Above: This is a rishi at the foot of a colonette at the main sanctuary. The word rishi mens seer, singer of sacred verses, inspired poet or generally, a sage. They all wear a long pointed beard and this representation, in meditation, reminds me of the regiments of rishis at the foot of upright columns at Angkor Wat. Above: This character is of a particularly ancient vintage and should be housed in a museum somewhere, well out of the public eye. Here he is posing on the second causeway leading to the upper terraces of Wat Phu, having just enjoyed his long-awaited visit to this unique Khmer site in Southern Laos.

Above: This character is of a particularly ancient vintage and should be housed in a museum somewhere, well out of the public eye. Here he is posing on the second causeway leading to the upper terraces of Wat Phu, having just enjoyed his long-awaited visit to this unique Khmer site in Southern Laos.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

The sacred spring

Fawthrop on Preah Vihear

The row over the Preah Vihear temple has been simmering for hundreds of years. World Heritage Status has brought it to the boil.

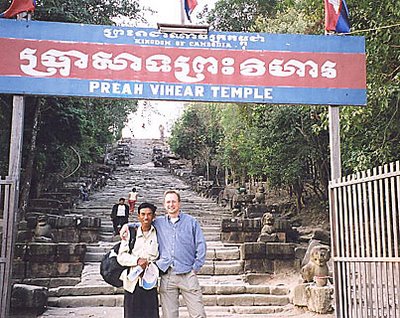

Preah Vihear, a stunning temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, is perched on a Cambodian cliff-top straddling the Thai border. It was finally awarded World Heritage status this month, despite fierce protests from ardent Thai nationalists and the parliamentary opposition in Bangkok. Now, according to a Cambodian official, 40 Thai troops have crossed the border and entered the temple complex. The temple's ornate structures date back to the eleventh century, but the site was occupied two hundred years earlier. Preah Vihear has become an explosive issue in domestic Thai politics. It has also exposed how narrow-minded nationalism can obstruct efforts at world conservation. Indeed, according to the Thai opposition leader Abhisit Vejjajiva, the dispute over the temple's ownership is the "knockout punch" that could bring down the Thai government.

Unesco's World Heritage Committee should be congratulated for their refusal to bow down to frenzied claims that Thai sovereignty is being compromised. Much of the furore has focused on the 4.6 kms of disputed land surrounding the temple, which is claimed by Thailand. But the UN committee judged the Cambodian claim – pending since 2001 and repeatedly delayed by Thai objections - on its merits, and refused to cave in to the barrage of Thai petitions and political pressure. The foreign minister was forced to resign over his inept handling of the issue. Cambodia and Thailand share much in common - culture, Buddhism and many traditions - but rivalry has led to centuries of distrust and simmering border disputes. Cambodians remember with pride that the temples of Angkor were the foundations of southeast Asia's greatest empire, the Khmer, which took in parts of what are today Laos, Thailand and Vietnam and Burma. Preah Vihear is now added to the legendary Angkor Wat at the heart of this Khmer civilisation.

The death blow to 400 years of Khmer rule was dealt by an invasion from Siam in 1431. Since the decline and fall of the great empire of Angkor during the 14th and 15th centuries, Cambodia has suffered a series of invasions and loss of temples and territory. The only victory achieved by the Khmer people during this long period of humiliation and retreat was won not on the battlefield but in the courts. In 1962, the International Court of Justice in The Hague made a landmark ruling that Preah Vihear – then under Thai military occupation - was a Khmer temple and part of Cambodia's heritage. The Thai dictatorship reluctantly complied with the judgment, removing Thai soldiers from the temple, while the ownership of the surrounding 4.6 kilometres was left unresolved. During the last 46 years Thailand has shown little interest in helping to preserve the temple. Khmer Rouge forces seized it in 1993 under the noses of a Thai military base stationed nearby. Pol Pot's soldiers were not there to engage in archaeological pursuits, but to deny the Phnom Penh government control over a sacred and symbolic site as part of an insurgency backed by the Thai military. This policy of complicity with the Pol Pot forces led to further Khmer disgust with their more powerful neighbour.

The centuries of accumulated grievances felt by ordinary Cambodians erupted in 2001 when they burnt down the Thai embassy in Phnom Penh. Even today, most Thais still have little or no idea why their embassy burnt down, much less why Cambodians feel that Thailand has engaged in cultural chauvinism. According to several Thai historians, Thai schools teach a very partisan version of events in which Cambodia's vast contributions to Thai culture and society are scarcely mentioned, much less acknowledged. Historian and author Professor Thongchai Winichakul recently said he believed the Preah Vihear World Heritage issue "has gone beyond technicalities. It is abused to arouse delusion that the temple belongs to Thailand and a desire to revive the claim. The purpose is to generate hatred in Thai politics." Ultimately, World Heritage sites like Preah Vihear are supposed to transcend national squabbles and boost conservation efforts in both Thailand and Cambodia. But despite Thailand's rapid economic progress, this centuries-old vendetta drags on.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

More awards for Kari and George

Parenting honor, for first time, goes to adoptive pair - Rocky Mountain News, USA

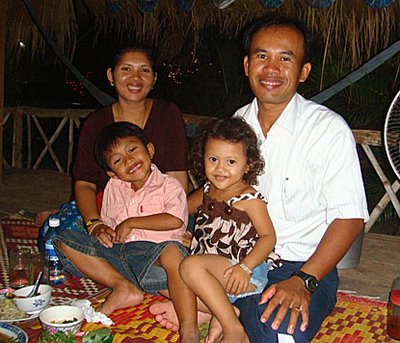

George and Kari Grady Grossman went to Cambodia looking to adopt a son seven years ago and wound up adopting a country. On Sunday the Fort Collins couple was named the American Family Coalition's Colorado Parents of the Year, the first time the honor has gone to an adoptive couple in Colorado. The Grossmans are parents to Grady, now 8, whom they brought from Cambodia, and Shanti, 4, whom they adopted in India. The couple also started a nonprofit called Sustainable Schools International, which tries to help Cambodian villages build and maintain schools through economic development. On Monday, they talked about parenting and adoption.

Q: What’s the secret to being good parents?

Kari: I don’t know if we have any secrets other than for us in our situation with kids who were adopted from another country I think one of the few secrets to that is that we experience their walk through understanding their adoption and understanding the loss that goes with losing your country and your birth culture with them. Meaning that we share the story with them. We talk about the truth of the stories. And we don’t have any hidden information. I think in adoption that used to be the case. I don’t know if there was shame associated with it or whatever, but people didn’t share the whole truth. And with our kids we’ve been talking about the truth since day one. Of course, since being adopted means that there’s loss involved, both our kids have to face and learn about loss early in life. And I think that’s a good life skill to have because all of us face losses in our lives.

So as parents we walk through that with them. We celebrate adoption every day. We celebrate who they are and their uniqueness every day. I think that’s one of the things that I’ve always noticed with friends who have non-adopted children, biological children. Maybe because they look different to us, we really see whom they are coming out. That’s not so much a reflection of who we are, because they don’t look like us. Maybe it’s a little easier to separate yourself and say, watch this person emerging and what can I do to support that, whatever it is, instead of putting my own opinions on it.

George: There was a woman we met a long, long time ago, way before Kari and I were married. And she said the only thing you can really give your children is a happy childhood. We have always remembered that. It was like a runoff line that she gave us and we’ve always tried to do by that and to live by that with the kids. I think that would be my one advice for all sorts of things: try to give your children a happy childhood. It’s not about money. It’s really about spending time with them and doing things with them and finding out what they’re interested in and kind of playing with them at that level. Because really what they want is your attention and your time and your love.

Q: What would you say were the most challenging aspects of your two adoptions?

George: The first adoption was patience, because at that point we had no children and so you walk by the bedroom that he or she will go in and the fact that once you start the process, a lot of things are beyond your control. So it requires a lot of patience, a lot of faith and a lot of support for each other while this process is going on. I’d say that’s the biggest thing with the first adoption. The second one, you already have a child, so you don’t think that much.

Kari: On our second adoption it seemed that the information that we were being given was that Shanti was gross motor delayed. She was older. She was almost two. And so we basically had to sit down and say to ourselves, you know, are we accepting a special needs child, a child that will be physically handicapped? What could we really infer from this medical information that was coming from across the planet? So it really was kind of a leap of faith. Interestingly, by the time she came to us, she has totally overcome her gross motor delay. Apparently she had problems with her legs. They didn’t work properly for the first year. But by the time she came to us she was quite capable of walking and she bounced on the trampoline and now she’s our athletic one. So you know, you just go with it.

Q:What brought you to Cambodia in the first place?

Kari: Before we went on our adoption trip, we, like most folks, didn’t know much about Cambodia other than it was next to Vietnam. We’d heard of Pol Pot. We’d heard of the Khmer Rouge, but we really didn’t know. And so we were basically praying a lot about adopting. You get into that world and there’s a lot of information…it’s overwhelming. You just have to step back a bit. So anyway, we were actually starting the process of adopting from China. Primarily because we were with other people who were adopting from China and they were telling us where to go and what to do. But one of those people put us on an e-mail list that was four families who had adopted from China. And on that list one day, someone posted a message about these children in Cambodia, that there were all these children waiting to be adopted.

I called it the fatal click because with that click, up came these faces of beautiful children. And I said to George, I have to find out about this. So over the period of the next two weeks, I called everywhere I could find for information about Cambodia and the adoption process. Then one day, I called my mother. My mother was in Maine. I told her, ‘Mom, you’re not going to believe this but I’ve been learning about Cambodia.’ And she said, Cambodia! I just came from the hairdresser and this woman was there and she had adopted children from Cambodia and I got all the names for you of people to call. And she started reading them off and I had already called the same people. And as I was having this conversation, George walked in the door with National Geographic had a cover story about Cambodia and he plopped it down. And I just looked at him and said: OK. Got it. You don’t need to send any more signals. We got the message.

The story also ran in the Coloradoan.com newspaper yesterday.Fort Collins couple 'Parents of the Year'

Grossmans have two adopted kids and built a school in Cambodia.

Kari and George Grossman didn't see it coming, but July 7 turned out to be a shocking and humbling day. The Fort Collins couple not only found out they were named the 2008 Colorado Parents of the Year, but they also found out Kari Grossman's book, "Bones that Float, A Story of Adopting Cambodia," won the Independent Publisher Book Award for Peacemaker of the Year. Her book is about the couple's experience of adopting their 8-year-old son Grady from Cambodia and then building a school in Cambodia.

The Grossmans were selected as Parents of the Year by the Colorado Parents' Day Council not only for parenting Grady and his 4-year-old sister, Shanti, whom the family adopted from India, but for their work building and running the Grady Grossman School in Cambodia. The Grossmans were also selected because their work in Cambodia models a life of service for their children. "I never thought about how it would have an effect on our own children's point of view," Kari Grossman said, adding that her son recently told her that when he was "old like Grandma, I'm going to work very hard for the GG School." "To see what he was getting out of it touched me," she said. Kari Grossman said the family didn't even know they had been nominated for the parenting award, which celebrates Parents' Day - a nationally recognized day of remembrance for parents celebrated on the last Sunday of July. "It's just the way our life and the way our family works," George Grossman said of the family's work in Cambodia. "Maybe (the award) is just an affirmation that we're doing something right as a family. We really don't think it's all that extraordinary, but I feel rather humbled by the whole thing."

The Grady Grossman School provides education for five rural villages in Cambodia and is its village's only permanent structure. It started with 50 children in 2001, and today there are 500 students, seven teachers, a solid cement structure with a water well and a solar-powered computer. The school is a part of the Grossmans' foundation, Sustainable Schools International. With a quarter of the proceeds going to the school, Kari's book has raised about $50,000 for the school. The couple also makes trips to Cambodia three or four times per year. "I've never seen a couple go to the extent that the Grossmans have," said Peggy Yujiri, spokeswoman for the Colorado Parents' Day Council. The Grossmans are among 50 nominees for National Parents of the Year, which will be announced on Parents' Day, July 27. They were honored at a dinner on Sunday in Denver along with 11 other Colorado couples.

Wat Phu continued

Celebrations at Olympic

Monday, July 14, 2008

Guidebook chat

Connoisseurs' Guide to Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, the brand new series has kicked off with Vietnam and future publications will include Cambodia, Myanmar, Shanghai, Japan, Thailand, North India and Nepal. Published last month, To Vietnam With Love is edited by Kim Fay who guides readers through the country with more than fifty expatriates, travelers, and locals as they reveal their favorite haunts through personal stories. Stay overnight with a local hill tribe, climb Southeast Asia's highest mountain, tour historic French villas, dine on local specialties from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City, and learn how to give back to the country while you're visiting. And that's just the beginning.

Connoisseurs' Guide to Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, the brand new series has kicked off with Vietnam and future publications will include Cambodia, Myanmar, Shanghai, Japan, Thailand, North India and Nepal. Published last month, To Vietnam With Love is edited by Kim Fay who guides readers through the country with more than fifty expatriates, travelers, and locals as they reveal their favorite haunts through personal stories. Stay overnight with a local hill tribe, climb Southeast Asia's highest mountain, tour historic French villas, dine on local specialties from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City, and learn how to give back to the country while you're visiting. And that's just the beginning.To take a peek into the forthcoming To Cambodia With Love edition of the series, click here.

Sunday, July 13, 2008

Causeway to heaven

Birthday bash

Saturday, July 12, 2008

Wat Phu's southern palace

Preap Sovath

Northern palace at Wat Phu

Vittorio Roveda describes him as the architect of the gods and of the universe. He's the master workman who sharpens the axe of Agni and forges the thunderbolts for Indra; he is a lord of the arts, executor of a thousand handicrafts, carpenter of the gods and fashioner of all ornaments. So, he's pretty important by the sounds of it. His attribute is a stick of command, the danda, or in some cases the measuring ruler. In the Ramayana epic, he's the supreme architect who builds the city of Lanka, as well as being the father of Nala who constructed the bridge between Lanka and the continent, allowing Rama to cross the sea and attack Ravana's city. Just in case you were interested!

Above the lintel on the blind eastern door is a triangular pediment featuring Umamahesvara - a very simple rendering of Shiva and Uma, his consort, riding the bull Nandin. The other pediments on show are less decorative and contain minor gods. I couldn't gain access to the western lintel and pediment because of the dense vegetation. Behind the southern palace is a building under reconstruction with the help of a team of experts from Italy and which is called the Nandin hall (the name of Shiva's sacred steed) or library.

Friday, July 11, 2008

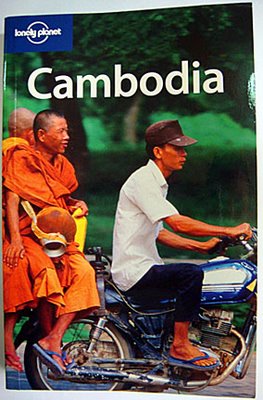

LP Cambodia 6

Exclusive! - Here's the front cover of Lonely Planet - Cambodia, the 6th edition, though it's not available in bookshops until next month. This copy is still warm having left the printers in Singapore and found its way to the coordinating author Nick Ray's desk. I've managed to wrestle it from his tight grasp for a few minutes to have a skim through and its bigger and better than ever. Trying to keep abreast of a country changing as fast as Cambodia must've been a nightmare for Nick and his fellow co-author Daniel Robinson, who has returned to the fold after being one of the authors of the first LP Cambodia in 1989, but they've managed it particularly well in my view. The book is forty pages longer than the last edition (August 2005) and there are more words, and lots more places featured, than ever before for the $21.99 price-tag. The photo count has dropped to just 23 - which is probably too few - though the maps remain at 46 and LP have jumped on the eco/green bandwagon with a new Green Dex to accompany the usual index. The numerous fact boxes highlight dining and shopping with a cause and also include interviews with half a dozen notable Khmers including food tycoon Luu Meng and the sweeper of Ta Prohm, Nhiem Chun. The 'our picks' will cause some discussion among travelers in the sleeping and eating sections but I was pleased to see my own fave guesthouse, Shadow of Angkor in Siem Reap, get flagged. Angkor is, as always, comprehensively covered and there's important details on one of the newest destinations to open up, the Cardamom Mountains. LP Cambodia 6 gets a definite thumbs-up from me, and not just because Nick is sat across the office! The big question is - when will the photocopied versions hit the streets of Phnom Penh and Siem Reap?

Exclusive! - Here's the front cover of Lonely Planet - Cambodia, the 6th edition, though it's not available in bookshops until next month. This copy is still warm having left the printers in Singapore and found its way to the coordinating author Nick Ray's desk. I've managed to wrestle it from his tight grasp for a few minutes to have a skim through and its bigger and better than ever. Trying to keep abreast of a country changing as fast as Cambodia must've been a nightmare for Nick and his fellow co-author Daniel Robinson, who has returned to the fold after being one of the authors of the first LP Cambodia in 1989, but they've managed it particularly well in my view. The book is forty pages longer than the last edition (August 2005) and there are more words, and lots more places featured, than ever before for the $21.99 price-tag. The photo count has dropped to just 23 - which is probably too few - though the maps remain at 46 and LP have jumped on the eco/green bandwagon with a new Green Dex to accompany the usual index. The numerous fact boxes highlight dining and shopping with a cause and also include interviews with half a dozen notable Khmers including food tycoon Luu Meng and the sweeper of Ta Prohm, Nhiem Chun. The 'our picks' will cause some discussion among travelers in the sleeping and eating sections but I was pleased to see my own fave guesthouse, Shadow of Angkor in Siem Reap, get flagged. Angkor is, as always, comprehensively covered and there's important details on one of the newest destinations to open up, the Cardamom Mountains. LP Cambodia 6 gets a definite thumbs-up from me, and not just because Nick is sat across the office! The big question is - when will the photocopied versions hit the streets of Phnom Penh and Siem Reap?Another new arrival within the next month, though we haven't seen a copy yet, will be one of the brand new pocket guides from the Lonely Planet Encounter series that will focus on Angkor & Siem Reap. Created for the savvy visitor on a two-to-five-day trip, the compact guide (6x4") fits easily into your trouser pocket and will cost $11.99. As you might've guessed, Nick Ray is the author.

If you were wondering about some of the other guidebooks on Cambodia, Rough Guide will bring out their 3rd edition for Cambodia next month (authors are Steven Martin and Beverley Palmer), whilst Footprint's 5th edition (author Andrew Spooner) came out a couple of month's ago.

New short movie - Residue

A new historical fiction short movie, inspired by true events surrounding the 1970 Lon Nol coup in Cambodia and the tragic knock-on of five years later when the country descended into a genocidal Khmer Rouge hell, has been accepted into the San Diego Film Festival in September and Residue looks set for a run at the myriad of film screenings that take place in the States and around the globe. Produced by the same team that completed the comedic short film The Perfect Date last year, Residue is directed by Nathaniel Nuon, who co-wrote the film with actor Jared Davis. It begins with the desire by the CIA to halt the spread of communism into Cambodia by triggering the Lon Nol coup with assistance from a group of 12 secret Cambodian army soldiers who believed they were doing what was best for their country. The film then jumps forward to 1976 and the resulting Khmer Rouge genocide where one man manages to escape and carry out his own revenge on the men he feels are responsible. Two of the film's actors, Poleng Te and Kit Seng actually survived the Khmer Rouge period and bring that wealth of experience to bear in the production. You can find out more about the movie here.

A new historical fiction short movie, inspired by true events surrounding the 1970 Lon Nol coup in Cambodia and the tragic knock-on of five years later when the country descended into a genocidal Khmer Rouge hell, has been accepted into the San Diego Film Festival in September and Residue looks set for a run at the myriad of film screenings that take place in the States and around the globe. Produced by the same team that completed the comedic short film The Perfect Date last year, Residue is directed by Nathaniel Nuon, who co-wrote the film with actor Jared Davis. It begins with the desire by the CIA to halt the spread of communism into Cambodia by triggering the Lon Nol coup with assistance from a group of 12 secret Cambodian army soldiers who believed they were doing what was best for their country. The film then jumps forward to 1976 and the resulting Khmer Rouge genocide where one man manages to escape and carry out his own revenge on the men he feels are responsible. Two of the film's actors, Poleng Te and Kit Seng actually survived the Khmer Rouge period and bring that wealth of experience to bear in the production. You can find out more about the movie here.Author Sue Guiney is currently writing a novel set in Cambodia. A New Yorker now living in London, she visited Cambodia several years ago and like most, it left a big impression on the author of novels, plays and poetry. Her published works include her first novel, Tangled Roots and a collection of poems, Dreams of May : A Play in Poetry. Find out more about Sue Guiney here and keep an eye out for her novel.

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Welcome to Wat Phu

Here are some photographs from my recent visit to Wat Phu as I entered the historic site, constructed mainly in the 11th century but built on an older site and also added to in later centuries. The man-made basin in the photos is one of three and marks the eastern end of the temple axis. It was dug later than most of the surviving temple and at its western end, a modern derelict pavilion was recently removed leaving behind a terrace of sandstone blocks. From the terrace, the lower causeway begins, stretching some 250 metres towards the 'palaces' - one of the longest approaches of any Khmer temple. Originally the causeway was lined with nagas and boundary stones, many of which have been erected during recent renovations. The view looking up towards the mountain revealed the summit shrouded in low cloud and the forested slopes a beautiful green as the sun peered through the early morning mist. Breathtaking.

Memoirs

I'm not convinced about the title of this self-published new memoir, but Cambodian author Dara O Sok's The First 22nd Years takes us on a roller-coaster story from his earliest memories in Battambang,

I'm not convinced about the title of this self-published new memoir, but Cambodian author Dara O Sok's The First 22nd Years takes us on a roller-coaster story from his earliest memories in Battambang,  through the curse of the Khmer Rouge years where his family was torn apart and onto his eventual relocation to America and service with the US Navy. Sok's autobiography has just been published and is available through Xlibris.com. Another memoir listed by Xlibris is the 2002 published, 348-page biography by Saoran Pol La Tour, with Vivian Kirkbride, titled Vantha's Whisper. It tells the extraordinary story of Saoran and Vantha through the ordeal of the Khmer Rouge regime that ripped their beloved Cambodia apart.

through the curse of the Khmer Rouge years where his family was torn apart and onto his eventual relocation to America and service with the US Navy. Sok's autobiography has just been published and is available through Xlibris.com. Another memoir listed by Xlibris is the 2002 published, 348-page biography by Saoran Pol La Tour, with Vivian Kirkbride, titled Vantha's Whisper. It tells the extraordinary story of Saoran and Vantha through the ordeal of the Khmer Rouge regime that ripped their beloved Cambodia apart.The celebrations have died down a bit after Cambodia reveled in the news that Preah Vihear has achieved World Heritage status. Street parties, open-air concerts, fireworks, bell-ringing at pagodas and much tub-thumping accompanied the news that Cambodia has prevailed over their Thai neighbours, who made themselves look extremely petty by creating such a fuss over the listing in the last few weeks. Seen as a victory over their Thai opponents, Cambodians are sticking out their chests with pride over their success.

I, on the other hand, am nursing two very sore feet after my first venture back into the sporting environment. It was a simple five-a-side game of football under floodlights last night at City Villa but the soles of my feet took a battering and blistered badly. So much so that I will have to forgo any more football for a couple of weeks until they recover. So to accompany my aching bones, I am walking with a pronounced limp and feel - and look - more like an old-age pensioner than the fit and virile individual I see when I look in the mirror [no disrespect intended to any pensioners reading this column].

Finally, I saw a glimpse, and that's all it was, of the brand-new, hot off the printing press, Lonely Planet guide to Cambodia (the traveler's bible in this part of the world) this morning. As I work alongside the guidebook's editor, Nick Ray, he's been sent a copy of the 6th edition before they hit the bookshops (or are photocopied and sold on the streets of Phnom Penh and Siem Reap) but he's now taken it home to check every word! Hopefully, I might get to actually handle it tomorrow!

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Dolphin watch

Battle to save Cambodia dolphin - by Guy Delauney (BBC News)

Sun Mao leans forward in the boat, shades his eyes with his hand, and squints across the wide expanse of the Mekong River where it twists through the town of Kratie. He is looking for one of the world's rarest mammals - the Mekong Irrawaddy dolphin. Older people in this part of northern Cambodia talk of how they used to take the dolphins for granted. Little effort was needed to see them in their dozens. Now, scientists say, there are less than 100 remaining.

National heritage

With a practised eye, Sun Mao spots a group of five dolphins, collectively known as a pod. They briefly break the surface as they come up for air - grey-brown, bullet-headed and exhaling with an old man's rasp. It is an awe-inspiring sight, but nothing new to Sun Mao. As part of a local organisation, the Cambodian Rural Development Team (CRDT), he has put years of work into preserving the dwindling population. For him it is an issue of national heritage. "This is the last place for these dolphins in the world," he says over the clatter of the boat's outboard engine. "We have to conserve and keep them alive in this river for our next generation." CRDT has tried to educate the local human population about what they can do. A government-enforced ban on the use of gill nets - nets set vertically in the water so that fish swim into them and are entangled in the mesh - has cut down the number of dolphins accidentally caught by fishermen. Instead, CRDT has helped locals to reduce their reliance on fishing by offering alternatives such as poultry farming. Villagers on Pdao Island, just outside Kratie, greet Sun Mao as an old friend as he clambers up the muddy riverbank.

Tourist influx

They happily show off their CRDT-sponsored chickens, water-pumps and fish ponds, and declare themselves delighted to be part of the dolphin preservation efforts. It would be a heart-warming tale, if only the statistics were not so brutally depressing. A scientific survey taken three years ago estimated the dolphin population at 127. The latest study by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) puts the figure at 71. It comes as a devastating blow after all the work that local and international organisations have put in. As well as banning the use of gill nets, the government has established a network of river guards to patrol the dolphin habitats. While CRDT has been working with the local human population, WWF scientists have been looking into ways of protecting the dolphins. Everyone was hoping that the dolphin population would at least stabilise, if not flourish. Payback would come in the form of an influx of tourists to see the pods at play and bring much-needed revenue to the local economy.

Contaminants

That dream recedes as each dead dolphin washes up on the banks of the Mekong. Most worryingly, most of the recent casualties have been calves. Without the babies, there is no future for the species. "There are theories that the immune systems of the dolphins have been compromised by stress," says Richard Zanre, dolphin programme manager for WWF. "The river environment has been encroached upon by new developments. There is also the problem of contaminants in the river." The answers need to be found quickly. As it stands, WWF still classifies the remaining population as "sustainable". If the numbers fall much further, however, there will no longer be enough diversity for the dolphins to breed successfully. That would spell the end for this unique species.

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

More on Harpswell

Alan Lightman of Harpswell - gives to others : by Caitlin M Elsaesser (TimesRecord.com, Maine, USA)

Alan Lightman has a long list of accolades attached to his name. He was the first professor at MIT to teach in both the humanities and science departments. He is the author of an international best-selling book, "Einstein's Dreams." But what has satisfied him the most is his charitable work in Cambodia. Having grown up in an upper-middle class community in Memphis, Tenn., Lightman said his time has come to give back. "I feel it is my responsibility to help people who have not had these privileges," he said, with a light drawl that reveals Southern roots. To that end, Lightman and his family established the nonprofit Harpswell Foundation in 1999, named after the location of their island retreat. Since then, the foundation has built a school in a remote Cambodian village and a women's dormitory and leadership center in Phnom Penh. The foundation manages the progress of the 30 girls in the dormitory.

Now Lightman is embarking on his most ambitious project yet: he wants to build another women's dorm and create an endowment to maintain the dormitories indefinitely. He estimates the cost for that to be $1.8 million. He admits it will be no easy feat. "I've struck out a few times," he said, referring to fundraisers on which he lost money. But this writer who loves solitude is not giving up. "I believe in the mission and the cause," he said. For nearly 20 years, Lightman and his family has summered on a small island off the rocky coast of Harpswell. Twenty minutes driving on narrow roads leading to the sea and 10 minutes riding on "Lightwave," the family's small boat, bring the Lightmans to their island retreat. "Many days I am the only person on the island," Lightman said. "That is a great feeling." The house has no Internet or phone connection, a reflection of Lightman's values. Lightman did not use e-mail until recently. Though he is sometimes critiqued by colleagues at MIT who must hand-deliver memos, Lightman relishes peace. But Cambodia pushed Lightman into electronic communication. Now, not only is Lightman on e-mail nearly every day for his work in Cambodia, but he often makes trips into nearby Brunswick from his island retreat specifically to write e-mails to the dormitory girls.

Falling for Cambodia

Lightman visited Cambodia with his daughter, Elyse, three years ago at the prompting of a friend. When he and his daughter visited a remote village of 600 people, women with babies on hips begged the Lightmans to build them a school. Lightman was amazed by their positive attitudes, especially in light of their past. The village consists of a small sect of Muslims, the whole of which constitutes less than 5 percent of the Cambodian population. These Muslims were targeted in mass killings in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia's ruling party from 1975-79. Led by Pol Pot, historians say the regime was responsbile for slaying up to 2 million of the country's people. "In spite of their miserable history, they still had hope in education," Lightman said. "There was no way we could not help them." In the following two years, Lightman raised $30,000 presenting slide shows and writing e-mails to friends. He built the village's first school. Lightman, who is Jewish, also funded the construction of a mosque for the village using his own money.

Help from a native

Lightman's school contractor was Chea Veasna, the fourth woman in Cambodia to receive a law degree. Because she was not allowed to stay in the mosques, as boys were, she lived for four years in a small muddy space with no bathroom underneath the law school. Veasna and Lightman hatched the idea together of building a women's dormitory to help women who experienced similar obstacles. After building a dorm in Phnom Penh, he did a country-wide search for the top high school girls, combing application essays for leadership potential. "Most said they would help family and maybe their village," said Lightman. "While we admired that, we put those in the trash."

Thirty girls who wrote they wanted to help their country were asked to join the first class at the Harpswell Foundation dormitory and leadership center in Fall 2006. Lightman worked with dorm manager Peou Vanna to leave no detail unturned: they obtained a 50-percent university discount for the girls, launched enrichment classes, and armed students with information on how to be ladies in a city, which was necessary for girls moving from small villages to the biggest city in the country. Two years into the project, the results are showing, said Lightman. All the girls are first or second in their class, and university presidents have called Lightman to ask him for the secret to the girls' success.